T

he United States is preparing to take a leaf out of a successful program in Europe to shift road traffic to waterways, with the aim of dissolving highway bottlenecks, speeding goods to market, reducing fossil fuel consumption, saving highway maintenance costs, improving air quality and fostering economic development in markets that have had limited access to the broader world.

The Marine Highway program of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration resembles, even if it does not specifically mention, the Marco Polo initiative of the European Commission, launched in 2003. The EC predicts greater use of waterways (and rail) could remove as many as 500,000 trucks from European roads by 2020, and up to 1.2 million by 2050. For the three years ended in 2009 an estimated 58 billion tons of freight shifted from congested highways to other modes of transport, the EC says.

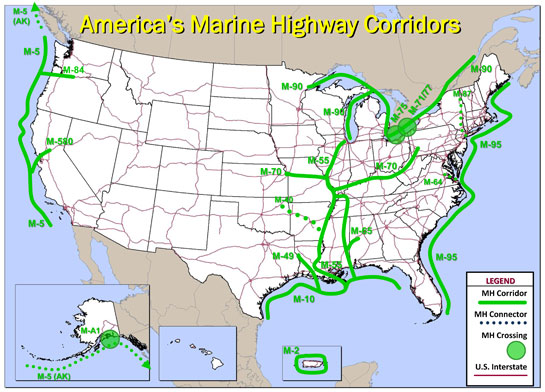

Those goals are similar to the ones that DOT Secretary Ray LaHood spelled out in September when DOT gave $7 million in initial funding to seven projects on the East, West and Gulf coasts and inland waterways, and said six others could apply for funding later after feasibility studies. The DOT sees 11 coastal and inland corridors and four connectors in its America Marine Highway program.

“There is no better time for us to improve the use of our rivers and coasts for transportation,” LaHood said.

The most ambitious project is the Gulf Atlantic Marine Highway that would link Charleston, S.C., and Galveston, Texas, using American-built container ships operated by American Federated Lines, a company owned by Percy R. Pyne IV and Tobias König, a German shipping investor.

Pyne says that AFL has raised $20 million and needs $250 million to build 10 ships within three years and up to 100 ships over the next 15 to 20 years. Pyne is enthusiastic about seeing a Marco Polo type initiative with its various incentives in the United States. The amount of freight that could move on European waterways has increased to 40 percent from 16 percent under the program, he noted.

Paul Bea, a Washington transportation consultant, cautions that Marco Polo is a very broad program, some of whose parts might not work in the United States. The marketplace is starting to do some of the same things in the U.S. —promoting more efficient movement of traffic, energy efficiency, labor efficiency — noted Bea, who is a strong supporter of the DOT effort.

Pyne can tick off the reasons why manufacturers and shippers need alternatives — but not substitutes — to hauling goods over the roads.

“Our country stands for growth and we can’t continue to grow without transportation,” Pyne says. “The coasts are four times more densely populated than the interior of the country, and population on the coasts is going to grow by 12 million in five years. How are you going to move goods from or to Miami? Because it won’t be possible on I-95.

“Trucks should be the first and last piece of a supply line,” Pyne says. “The first 200 miles could be on a truck or rail, the next 600 to 700 miles on water, and then back to a truck for the last 200 miles.”

The basic economics of water travel versus roads are clear. An average eight-barge tow can move as much freight as 120 railcars or 480 tractor-trailer trucks. Water travel is slower by far than road, so it is more suitable for non-time sensitive goods.

Other Routes, Other Links

Closer to home than Marco Polo, the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway (Tenn-Tom) is a model for how waterways can help local economies, by attracting and supporting heavy industries such as steel, furniture and agriculture and by linking inland markets to domestic and international customers.

The Tenn-Tom, a 234-mile (377-km.) channel, connects west-central Alabama and northeastern Mississippi to a vast inland waterway network. Studies have found that the Tenn-Tom has had an economic impact of more than $40 billion for the whole United States, and that more than 30,000 regional jobs depend on it, notes Mike Tagert, the Tenn-Tom’s administrator. “It is relatively cheap to maintain and has all kinds of other benefits,” he adds.

One project that DOT has awarded financing for is an expanded container-on-barge service between the Port of Itawamba (on the Tenn-Tom) and Mobile, Ala. The project is expected to relieve truck traffic from the I-65 corridor, where the current tally of 3,150 daily truck trips is projected to reach 25,000 by 2035, says the DOT. Tagert notes that plants in the region now receive and ship scrap metal, finished coils of steel and other heavy products to and from Brownsville, Texas, and Central and Latin America.

Asia and Latin America are increasingly important to the Midwest. The Tenn-Tom has an agreement with Panama to share information about the widening of the Panama Canal, which will bring very large container ships to the Gulf and East Coasts when the widening is completed in 2014. Tagert sees that as an opportunity for even more traffic from Asia and the West Coast to come up to the Tenn-Tom and the businesses it serves.

The Port of Galveston has signed a similar memorandum with Panama and is preparing to deal with the very large ships that will come through the canal, says Steven Cernak, port director. The port can now handle ships with a 45-foot draft, and eventually will have to go to 50 feet, he says.

Cernak is also overseeing a joint venture with the Port of Houston to build a new container terminal on Pelican Island, which will reduce a trip up the channel to Houston by 40 miles (64 km.). With two Class I railroad links and intercoastal water links, Galveston is well situated as a distribution center for the region, he says.

Water highway vessels such as Pyne’s are suited to bulk, and non-time sensitive products such as containers that are stuffed with bales of cotton, Cernak says. “It is far less expensive to move product by water than by truck,” he says. “If you are not replenishing stocks, it is fine.”

Ships are not the only vessels that the DOT is backing. It awarded $3.4 million out of its $7 million pool to the Cross Gulf Container service between Manatee, Fla. and Brownsville. Manuel Ortiz, a spokesman for Brownsille, says the port will purchase loaders, construct ramps and modify a barge so that more containers can be packed on it. Brownsville is a natural gateway to Mexican markets and has 40,000 acres (16,188 hectares) of vacant land available for new investments, he notes.

The Virginia Port Authority received $1 million to buy another barge so that it could run its barge service between Richmond and Hampton Roads twice a week instead of just once, and eventually link to international ports. “The Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel is notoriously congested and I-64 is equally congested,” says Joe Harris, a VPA spokesman. In addition to avoiding those delays, truckers save because they can drop goods at the barge for river transit and don’t have to make an empty run back.

Two other initiatives highlighted by the DOT are the West Coast Hub-Feeder distribution network and The Golden State Marine Highway, a 1,100-mile link connecting California, Oregon and Washington.

Capt Stephen Pepper of Humboldt Maritime Logistics, creator of the idea, notes this public-private project would use two barges to carry domestic and international containers. The whole project would cost $76 million. Pepper says that when a railhead was built near Stockton, Calif., distribution centers and retailers located nearby. The same type of investment could happen with Long Beach, Humboldt and other cities, he notes.