Corporate Water Asset Management in The American West: From Afterthought To Imperative

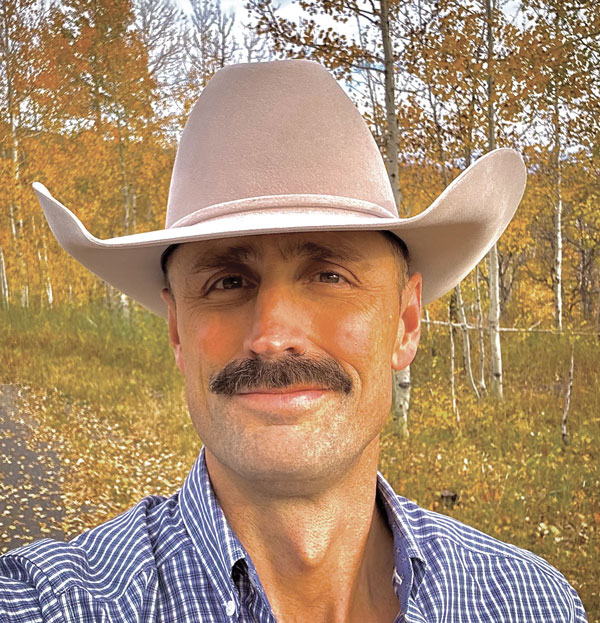

by James Eklund, Partner, Taft/ Sherman & Howard

Not long ago, water supply was the last thing on a corporate executive’s mind when planning a new industrial facility. Electricity? Sure. Permitting? Of course. Logistics? Always. But water?

That was assumed. Get a “will-serve” letter from the local utility and move on. Water was someone else’s problem — usually a public agency’s.

But we are not in that era anymore.

Today, water is no longer an assumed commodity in the Western U.S. It is a strategic asset. In fact, it may be the strategic asset when it comes to industrial site selection, permitting timelines and operational risk. The historical superstructure of government-managed water delivery — cheap, reliable, and invisible — is cracking under the pressure of climate extremes, aging infrastructure and legal fragmentation. Companies must now be water-literate, water-prepared, and water-resilient to thrive in the West.

Apple and pear orchards near Yakima, Washington

Photo by Brian Prechtel courtesy of USDA Agricultural Research Service

From Passive to Proactive

I’ve spent my career helping states, municipalities and companies navigate the complex and often contentious world of water law and policy in the West. As the architect of Colorado’s Water Plan, and now as leader of the Water & Natural Resources practice at Taft, I’ve seen a paradigm shift unfold in real time.

It used to be that industrial development anywhere in the U.S., West or East, followed a predictable pattern: Confirm zoning, confirm utility service, confirm transportation access. Water was a checkbox item — not a strategic variable.

Today, that checklist is outdated. Especially in booming industrial hotspots like Phoenix, the Front Range of Colorado, Austin, Reno, Southern California and Salt Lake City, site selectors are being forced to do their own due diligence on water. A “will-serve” letter is no longer sufficient assurance that water will be there in the volume and quality needed, at the times required and at a sustainable cost. Corporations are finding that their water exposure — if unaddressed — can jeopardize billions in capital investment and long-term operational viability.

Old Compact Collapses, Private Sector Expands

This shift is occurring because the traditional model — in which government agencies shouldered the burden of water infrastructure and allocation — is no longer reliable. The federal and state bureaucracies that once built dams, canals and reservoirs are now constrained by budget cuts, legal challenges, climate variability and political gridlock. The Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to 40 million people and supports 40% of U.S. GDP, is the most prominent example. But it is not the only one.

Governments are slow to act. Private industry cannot afford to be. Companies must now model their water supply risk like they would model energy pricing volatility, commodity exposure, or regulatory compliance. This includes:

- Diversifying sources: Can your operation flex between groundwater, surface water and reclaimed water?

- Stress-testing availability: How does your risk change in a drought year? A megafire year?

- Understanding legal rights: Are you protected by a priority water right, or are you relying on junior rights that could be curtailed?

- Monitoring quality: Is your water clean enough for production, cooling or discharge standards? Are PFAS or other contaminants an issue?

Sophisticated water planning is no longer a luxury. It’s risk management 101.

Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce Members pose by the Colorado River at the Foot of the Bright Angel Trail in November 1906.

Photo by Putnam & Valentine courtesy of National Park Service

The insurance industry sees this coming. I used to be the only lawyer in a room full of hydrologists and engineers at water risk conferences. Now I see actuaries and underwriters everywhere. Why? Because water risk is financial risk, and financial risk must be priced.

Increasingly, corporate actors are stepping into roles once reserved for government. They are building their own water infrastructure, investing in water reuse and recycling systems, and even acquiring water rights. A client of mine manufactures graywater systems that can reduce residential water demand by 25% — but their greatest challenge isn’t technical, it’s regulatory.

Without clear market signals or supportive policy frameworks, these kinds of technologies don’t scale. If government can’t deliver water certainty, then government needs to get out of the way of those who can.

Tools for Industrial Leaders

For corporate decision-makers, particularly those in real estate, manufacturing and logistics, water fluency needs to become part of the site selection and facility operations toolbox. Here are several practical steps to take:

- Use granular data: Tools like the Water Risk Atlas from the World Resources Institute now provide stress maps down to the county level. Leverage these to understand regional water risk profiles.

- Engage with providers early: Talk to utilities and ditch companies before committing to a site. Confirm infrastructure capacity, not just legal entitlement.

- Include water in ESG reporting: Stakeholders are paying closer attention to water usage and sourcing — not just carbon. Be prepared to answer those questions.

- Retain water-savvy counsel: Water rights and entitlements are governed by a patchwork of local, state and federal law. You don’t want to navigate that alone.

- Advocate for performance-based incentives: If you’re willing to invest in conservation or onsite reuse, policymakers should reward that — not pile on new compliance hurdles.

The New Reality

I’ll be blunt: In the West, we have enough water to sustain agriculture, cities and industrial growth — if we manage it correctly. But if we don’t, we don’t.

The solution isn’t to say no to growth. It’s to get smarter about how we support it. That means better forecasting tools, smarter infrastructure investments and a clear role for private industry as a partner — not a passive recipient — in managing our water future.

Water is no longer just a utility. It’s a supply chain issue. A permitting issue. A geopolitical issue. And ultimately, a leadership issue. The companies that will thrive in the Western U.S. over the next decade are those that treat water as the strategic asset it is — not an afterthought.

The future belongs to those who plan for it. In the American West, and increasingly nationwide and globally, that means planning for water — actively, intelligently, and collaboratively.

“We have enough water if we manage it correctly. But if we don’t, we don’t.”

— James Eklund, Partner, Taft/ Sherman & Howard

James Eklund leads the Water & Natural Resources practice at law firm Taft/Sherman & Howard. A recognized authority on water management in the American West, he was the architect of Colorado’s Water Plan.