When it comes to designing airports, the “aerotropolis” is one of the most influential development models out there. Yet among airport planners, it’s an open secret that the aerotropolis concept—which looks great on paper—actually doesn’t work very well in practice.

Why is that?

While researching my book Airport Urbanism over the last 10 years, I visited dozens of empty office buildings and underperforming logistics hubs at airports all over the world. Disappointed by what I saw, I started to think about how we can build on the strengths of the aerotropolis idea, move beyond its shortcomings, and update it for the demands of the 21st century airport — and the 21st century economy.

This article discusses some of the problems with the current airport-area planning paradigm. It explains how we got to where we are and speculates on how we can do better.

In the conclusion, I introduce a new development mode l called Airport Urbanism, or AU for short.

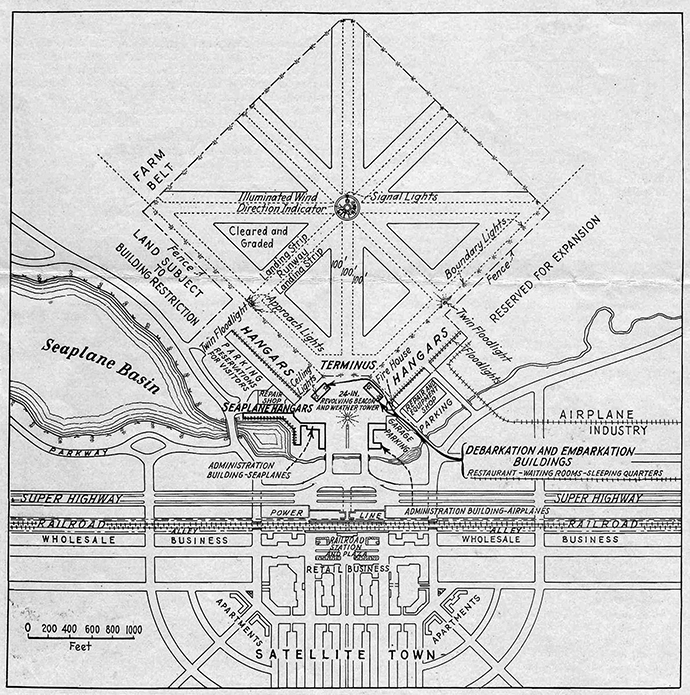

Since the early days of civil aviation, airport designers have tried to productively integrate the airport into the surrounding city — and to use the airport as a springboard for developing the communities located around the airfield. In the 1920s and 1930s, European architects suggested combining the airport with existing building types, such as amusement parks, exhibition halls and railway stations.

In the United States, meanwhile, designers thought that airports should be merged with other new building types that were considered exciting and futuristic: such as supermarkets, skyscrapers and — yes — parking lots. In 1939, the term “aerotropolis” was first used in a fanciful proposal for an airfield built on top of an inner-city office tower.

On both sides of the Atlantic, urban planners argued that airports could be used to develop satellite towns to service the emerging logistics industry. Some, like Le Corbusier, even thought that entire new cities should be built around the airport. Like the railway stations of the 19th century, airports would thus become the focal point of urban growth.

The notion that airports could serve as centers of urban development remained popular throughout the post-WWII era — but the idea never came to fruition.

However, in the 1990s, Dr. John Kasarda at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill began to resurrect some of these older concepts, and incorporated them into a development model that called the “aerotropolis.” He argued that the airport of the future would assume the role that traditional downtowns had played in the 20th century. Kasarda claimed that in a globalizing economy, accessibility to air transport networks would be essential for doing business. Land located near the airport would become a desirable place to build corporate headquarters, convention centers, and conference facilities. The airport area would also attract logistics firms that handled high-value products and time-sensitive cargo, such as food and flowers.

This was a really interesting idea — but the problem is that it’s not applicable to most airports.

A recent article in The Economist points to some of the aerotropolis’s major flaws. Simply put, the airport doesn’t have the “pull” of historic city centers, which have steadily regained their attractiveness over the last 20 years. If anything, multinational corporations (and their employees) want to be downtown now more than ever — in attractive, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. (Shifting demands placed on workspaces are also rapidly outpacing what’s available in the standard airport office park.) At the same time, the urban periphery, where most airports are located, has increasingly become the home of the poor and the poorly educated.

What about logistics firms? Well, they tend to set up shop wherever it’s cheapest to do so, as long as it’s within a one-hour drive of the airport. Storing cargo right next to the airport is often a lot more expensive — and a lot less appealing.

There are a few examples where the aerotropolis model has been a huge success: places like Schiphol in the Netherlands, or Las Colinas, Texas, near Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) airport. But these places do well because the airports that they’re attached to are located in the middle of a dense metropolitan region, equidistant from multiple urban centers.

It turns out that proximity to an airport is no guarantee for success.

Many factors contribute to the feasibility of an airport-area development, and reducing those factors to airport accessibility alone is a fatal mistake that urban scholars refer to as infrastructural determinism. But that hasn’t stopped airport authorities around the world from trying their luck anyway — leading to dozens of failed aerotropolis projects on nearly every continent.

In private conversations, many people who work in the aviation industry have readily expressed their doubts to me about the viability of the aerotropolis model. At a major European hub, one planner confessed that no one in his team believed that their airport’s aerotropolis plan would generate much revenue for the airport authority, or provide employment for the surrounding communities. He explained that there wasn’t enough demand for office space, and the local residents lacked the skills needed to work in a formal business environment. He also didn’t think that the subsidies being plowed into the project would ever be recovered.

“So why are you pursuing the project?” I asked.

“Because it’s our mission to develop real estate around the airport,” he replied. “So we have to plan something.”

“Even if you know it won’t work?”

He let out a weary sigh. “The problem is that there isn’t any alternative. The aerotropolis — the office park, the conference hotel, the convention center — it’s the only model. So that’s what we have to work with.”

But is it the only model? There must be other options.

On my website, airporturbanism.com, I introduce a new people-focused airport development model, designed to produce growth strategies that increase non-aeronautical revenue, improve the passenger experience, and benefit local communities.

Max Hirsh is a professor at the University of Hong Kong and a leading expert on airports and urban infrastructure.