If you want to gain a competitive edge in the race to hire talent, you may want to consider doing what many American workers have already done: Move out of the big city.

What many thought was just a blip during the COVID-19 pandemic — people fleeing big cities for the open space of suburbs, exurbs and rural small towns — has turned into a long-term trend.

Recent data from the federal government back this up. According to a report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, the overall rate of non-metro-area population growth during 2020-2021 (0.25%) exceeded the national rate (0.12%) for the first time since the mid-1990s. That trend continued in 2022 as the counties in outlying areas, including suburbs, exurbs and rural counties, saw their populations grow the fastest. Exurban counties grew by 1.9% while suburban counties grew by 1.5%.

In fact, the only areas that did not experience populations gains across the country last year were the urban cores. These high-population counties saw domestic migration outflows of more than 1.1 million people, according to Census data.

What’s happening? More in-depth research using Internal Revenue Service data reveals that the trend of people moving outward from large central cities actually began a few years before the pandemic and is continuing well after the peak COVID-19 years of 2020 and 2021.

Aaron Renn, a former senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Public Research, tells Site Selection that record inflation, remote working, rising big-city crime and lifestyle changes are prompting Americans to relocate from large urban cores to the hinterlands.

“Urban real estate prices are going up,” says Renn. “The price-to-income ratio in Columbus, Ohio, has increased by 50%. It is not as cheap as it used to be to live in big cities, even when those cities are in the Midwest. The same is true in Detroit. There have been tremendous increases in real estate prices in even the so-called affordable metros.”

USDA research shows that places once considered far-flung now rank among the most attractive magnets for in-migration. These include outlying counties in rural locations like the southern Appalachians, the Ozarks, the upper Great Lakes and the intermountain West. Others can be found adjacent to large metro areas, such as Nashville, Minneapolis-St. Paul and Dallas-Fort Worth, according to this same report.

One notable standout is the swath known as the Great Plains. Reversing historic trends, higher-than-average growth was experienced in non-metro counties in every state in this region.

Betting Big on Small Towns

As a result, many outlying counties across the country are now reaping record industrial investment windfalls. From the $20 billion Intel semiconductor factory by Intel in New Albany, Ohio, to the $100-billion commitment by Micron in Upstate New York, corporate America is betting big on the fortunes of small-town economies.

International investors are riding this wave too. Finnish housing manufacturer ADMARES announced May 31 that it will invest $750 million to build its first U.S. factory in Waycross, Georgia, where the company from Turku in Scandinavia will employ 1,400 workers in the making of affordable homes in a place known more for alligators and the Okefenokee Swamp than heavy industry.

With 13,502 people, Waycross ranks No. 81 in population in Georgia. It’s located in Ware County, which has 36,233 people and ranks No. 53 in Georgia. Just how rural is Waycross? The town is 237 miles from Atlanta and 122 miles from Savannah. In fact, the nearest big city is Jacksonville, Florida, and it’s still 80 miles and a 90-minute drive away.

None of that mattered to ADMARES, which found everything it needed, including a skilled and available labor pool, in the heartland of rural southern Georgia. “In addition to exploring opportunities in other states, Waycross is an ideal location for a transportation hub with easy access to major highways and extensive rail connections,” says Mikael Hedberg, founder and CEO of ADMARES. “Its proximity to the Port of Brunswick, one of the busiest ports on the Eastern Seaboard, offers a competitive advantage for global trade.”

ADMARES picked a greenfield site to build a 2.5-million-sq.-ft. plant on Highway 23 in Waycross. The new facility is expected to begin production of manufactured housing in late 2025.

Kristi Brigman, deputy commissioner of global commerce at the Georgia Department of Economic Development, said the Peach State beat out a number of competitors to land the project.

“ADMARES is a textbook example of how Georgia and our communities build long-term relationships that create future opportunities,” says Brigman. “ADMARES was referred to Waycross and Ware County by an industry partner who was familiar with the community. From there, Georgia entered ADMARES’ nationwide search, working the competitive project with state and local partners over the next eight months.”

Digging Into Rural Growth Factors

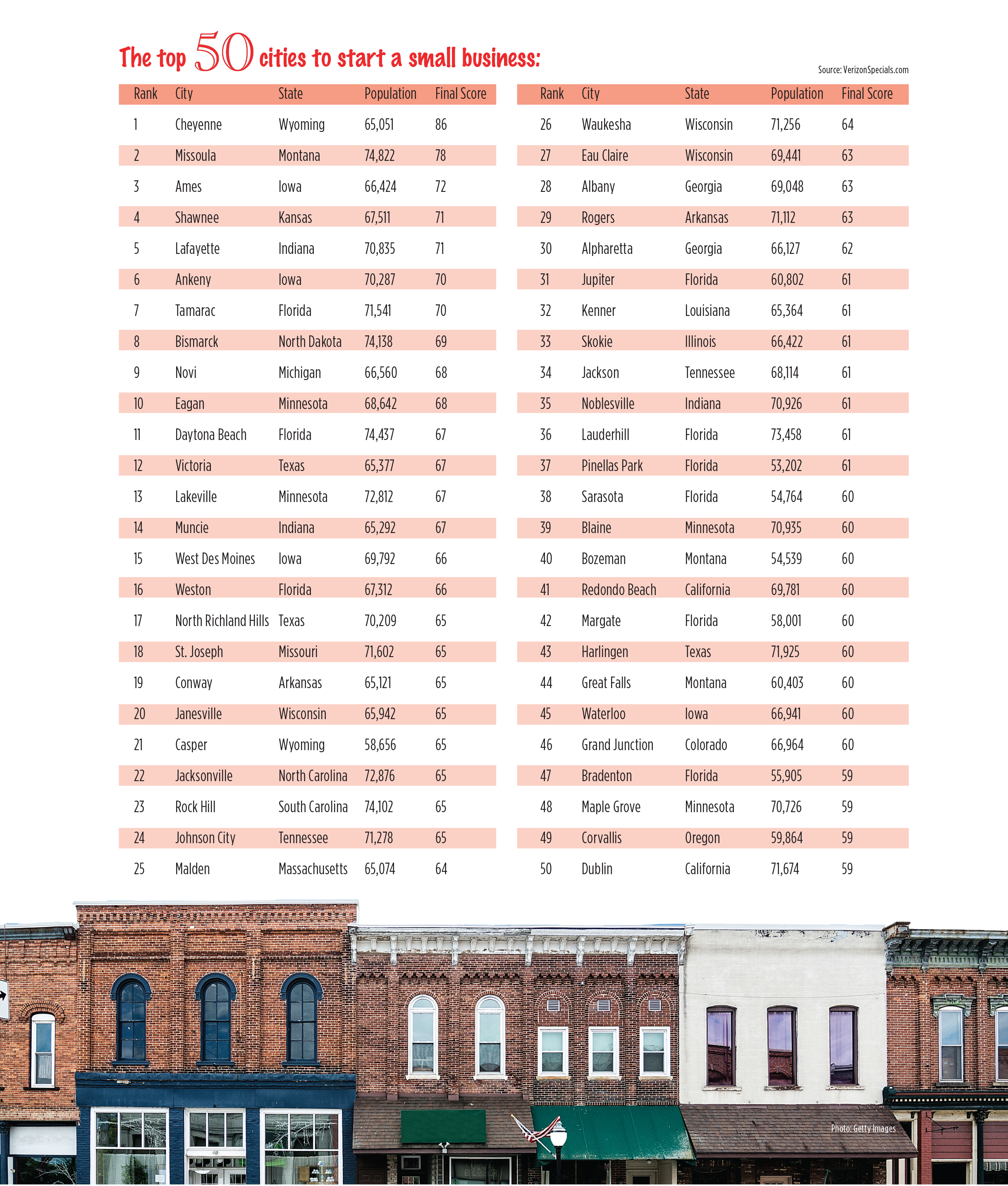

While many components go into producing a top-performing small town, a recent ranking from a telecommunications data provider sheds new light on the factors that the best business locations have in common. The sixth annual ranking of the Best Small Cities for Small Business, courtesy of VerizonSpecials.com, identifies these six factors as critical to success:

- Growing population.

- Highly educated workforce.

- Labor-friendly commute times.

- Favorable tax climate.

- Easy access to capital.

- Widespread broadband access.

Using these as criteria, VerizonSpecials.com looked at cities below 75,000 in population and came up with the top 50 cities for launching a small business (see p. 52). Cheyenne, Wyoming, with a population of just over 65,000, tops the list, followed by Missoula, Montana; Ames, Iowa; Shawnee, Kansas; and Lafayette, Indiana. Rounding out the top 10 are Ankeny, Iowa; Tamarac, Florida; Bismarck, North Dakota; Novi, Michigan; and Eagan, Minnesota.

Time to ‘Cowboy Up’ in Cheyenne

Wanting to know what separates Cheyenne from the pack, we reached out to Betsey Hale, CEO of Cheyenne LEADS, the economic development organization for Cheyenne and Laramie County.

ADMARES’ floating villa is an example of the manufactured housing that will be produced at the Finnish company’s 2.5-million-sq.-ft. plant in Waycross, Georgia.

Photo Courtesy of ADMARES

“We are at the intersection of Interstates 80 and 25. This is an ideal location for distribution operations,” she says. “We are just 10 miles from the Colorado border. You can get to Denver International Airport in about 90 minutes. Our cultural values are strong, and of course you can experience all the wonders of the great outdoors here — from the Sierra Madre Mountains and Jackson Hole to Yellowstone National Park and the Rocky Mountain West.”

Searing Industries, based in Rancho Cucamonga, California, moved to Cheyenne in 2012 and just completed another expansion, says Hale. “They are in the steel fabricating business. On June 13, we held a ribbon-cutting celebrating their third expansion here. This one was for 80,000 square feet.”

Lee Searing, president of the firm, noted that “Wyoming has proven to be an exceptional locating for Searing. We look forward to our continued growth in Cheyenne and serving our clients from the Cowboy State.”

Tamarac Flourishes in South Florida

Lori Funderwhite, economic development manager for seventh-ranked Tamarac in Broward County, Florida, says, “We have tripled in population since the 1980s, and we have about 2,000 small businesses. We are a business-friendly city that fosters initiatives for entrepreneurs like BOSS — Business One-Stop Shop — to help them get started and get their business off the ground. We also make heavy investments into our infrastructure. We have a Digital Information Technology Department that provides top-notch wifi access in our public parks; and we are a Platinum Permitting City.”

A rural , small-town lifestyle appeals to more and more people every day.

Photo: Getty Images

Success stories abound in this community of 72,000 people tucked in between Coral Springs, Sunrise and Fort Lauderdale. Sonny’s Car Wash Factory employs 660 people and will soon add100 more when its new 200,000-sq.-ft. warehouse opens. The world’s largest maker of conveyorized equipment for automated car washes, Sonny’s has been headquartered in Tamarac for over 20 years.

Aiming for the Top in Ames

Dan Culhane, president and CEO of the Ames Chamber of Commerce in Ames, Iowa, manages economic development for this city of 66,000 people in Central Iowa.

Downtown Cheyenne, Wyoming, the No. 1-ranked Small City for Small Business.

Photo Courtesy of Cheyenne LEADS

“Our central location, Iowa State University, the livability of this region, and the fact that we have 9,000 new graduates every year looking for work make this a great place for any business,” he says. “Merck recently bought a company that began in our ISU Research Park. Deals like that go a long way toward supporting and promoting our startup culture.”

Culhane adds that the president of ISU “has made entrepreneurship a key focus of every college in the university. The main challenge for any new business is finding that early-stage capital they need to grow. A typical investment is $50,000 to $200,000. We work with very young and early-stage companies here to help them find that critical funding.”

He notes that the firms choosing to locate in Ames are raising the local per capita income. “When they come to this market, they are paying their people at a wage rate that attracts people from other places,” he adds. “Economic development is about creating wealth for people. That is what we do here.”

Startups Abound in Ankeny

Derek Lord, economic development director for the City of Ankeny, Iowa, says that access to Interstates 80 and 35 in Greater Des Moines enables employers to tap into a deep talent pool.

“Situated between the core of the Ames MSA and the Des Moines MSA, companies in Ankeny are able to attract and hire a very talented and available workforce.”

Power Pollen is one of those firms. “They are an ag-tech company that preserves pollen,” says Lord. “They develop technology to preserve pollen and then deploy it into existing crops to increase yield. They chose Ankeny because it is close to the R&D coming out of ISU. They found that position between Ames and Des Moines as the sweet spot for growth.”

Craig Tool is another local success story. “They like the access, visibility and workforce in the area,” notes Lord. “They want robust amenities that make it easy to attract talent. They have found the perfect place to do that in Ankeny.”

Don’t Fall Prey to ‘God’s Little Acre’ Syndrome

Robert Pittman is founder of the Janus Forum and the Janus Institute at Lake Rabun, Georgia.

Robert Pittman, founder of the Janus Forum and Institute and co-author (along with Amanda Sutt and Rhonda Phillips) of “Rebooting Local Economies: How to Build Prosperous Communities,” was asked what advice he would give to small towns in America. A longtime site selection consultant and current advisor to Rabun County in the mountains of Northeast Georgia, here is what he had to say:

The more that elected officials, board members and all citizens understand economic development, the more likely the town will succeed in economic development. Once people understand that they can’t wait for economic development to drop on them like manna from heaven, and that they need to be proactive, they can get to work.

An expression I’ve used often to describe what can prevent economic development success is the “God’s Little Acre” syndrome. It goes like this: “Our town is a great place to live, raise a family and grow a business; why wouldn’t anyone want to move their business here?” People often see their town from the inside out, not from the outside in, like an executive or a site consultant who sees the weaknesses as well as the strengths. Understanding the competitive nature of business location decisions and how they are made, and that there are thousands of “God’s Little Acres” out there, helps instill in communities the will to create a good economic development program including becoming more development-ready and marketing to the right industries.

Related to the above, understand your community’s strengths and weaknesses, and what your real economic situation is. Unemployment may be low now, but is your economy based on industries and companies that are growing or declining nationally? In our world of rapid economic change, adjust your philosophy from “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” to “If it ain’t broke now, it will be, so we better have a plan to fix it.”

The above implies that communities should have a strategic plan complete with situation assessment (where we are now), a vision for the future (where we want to be), and a plan to get there.

Finally, look at other communities and how they have succeeded and be open to new ideas.

All the above implies that communities, especially rural ones that may have modest budgets, should have an economic development awareness and an economic development program (staff and budget). They should look at this not as a sunk cost but as an investment that will more than pay for itself.