The Scout has come a long way since International Harvester first produced the vehicle in 1961 in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The journey, in fact, has taken it about 700 miles to the southeast, depending on which route the driver wants to take to test the vehicle’s legendary ruggedness.

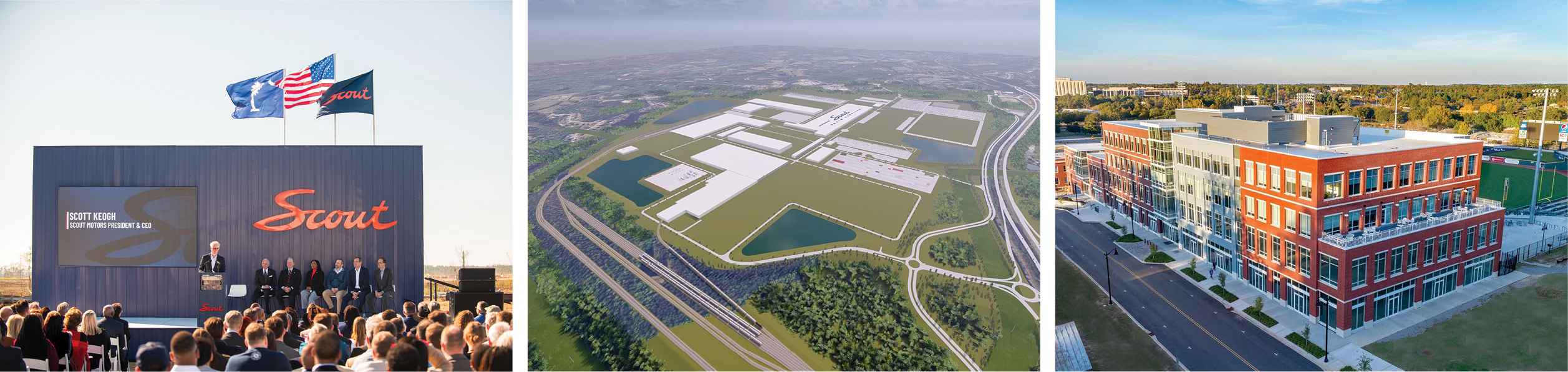

In February, Scout Motors broke ground on a new 1,100-acre production center at a 1,600-acre site in Blythewood, South Carolina, where the company, backed by Volkswagen Group, says it will begin manufacturing all-electric trucks and rugged SUVs by the end of 2026. The $2 billion investment, originally announced in March 2023, could create at least 4,000 permanent jobs and could produce as many as 200,000 Scouts annually at full capacity.

“Today is less about construction and a building and more about a calling and a community,” said Scout Motors President and CEO Scott Keogh. “We’re here to celebrate the revitalization of an American icon and the reshoring of American jobs. On this land — with our hands and with our technology — we will build great vehicles.”

The investment came three months after the company opened what it called “its first South Carolina office” in Columbia’s BullStreet District, a mixed-use development just one mile from the S.C. State House and anchored by Segra Park, home of the Columbia Fireflies Minor League Baseball team. The office will have a capacity of up to 175 employees.

The February groundbreaking for Scout Motors’ plant in Blythewood took place not far from where the company recently opened offices in Columbia’s BullStreet District.

Images here and on previous page courtesy of Scout Motors

As of the date of the groundbreaking over in Blythewood, Scout Motors had hired nearly 350 employees since its inception in 2022. The production center’s location, bordered by I-77 and Blythewood Road, is less than 20 miles north of Columbia and “near major cities and talent hubs such as Charleston, Charlotte, Greenville, and Atlanta,” the company said. “This proximity gives Scout Motors unrivaled access to major highways, ports of Charleston and Savannah, and colleges and universities focused on automotive engineering.”

Hidden Gem No Longer

South Carolina is home to more than 500 automotive-related companies that employ 75,000 people, led by the 11,000 or so at BMW, which is pursuing its own EV strategy with a $1.7 billion expansion that includes a $700 million battery facility. Through an executive order issued in October 2022, Gov. Henry McMaster helped lay the groundwork by prioritizing building EV infrastructure and advanced manufacturing training.

But precision manufacturing goes well beyond vehicles. One need only take a peek into Pickens County, located in a rural region of the Upstate adjacent to the Georgia state line that’s known for Lake Hartwell and Clemson University — one of those schools focused on automotive engineering.

Companies in the region benefit from partnerships with the five-campus Tri-County Technical College, the state’s No. 1 public two-year community and technical college in terms of student success. But a school at a different level is making its mark on industry in this region: Pickens County Career & Technology Center, where 1,800 high school students are enrolled and there’s a long waiting list to get in.

Ray Farley, executive director of Alliance Pickens South Carolina.USA, took me on a tour of the school last summer alongside his right-hand man, Alliance Pickens Existing Industry and Workforce Development Manager Jeromy Arnett, whose eyes well with pride and a bit of fire as he talks about the work ethic and skills of the area’s students. Farley doesn’t hold back either.

“The same year LSU stomped Clemson,” he says, as if everyone knows which year that was on the gridiron, “there was a competition in Department of Defense technical skills. Our high schoolers beat LSU in the machining competition. We like to say the Pickens County Career and Technology Center was the only Pickens County school to beat LSU that year. In fact, our kids beat 67% of the entries in that collegiate competition and finished in the top one-third.”

Farley’s organization has trademarked the phrase Scholar-Technician®, whose graduates find good-paying jobs quickly. Many of them work or intern in Pickens County Commerce Park in Liberty, which opened 19 years ago and last summer filled up with the arrival of FN America, which makes small arms for the U.S. military. The $33 million, 100,000-sq.-ft. facility joins the company’s other primary manufacturing operation in the state capital of Columbia.

Farley says one reason the workforce development focus his community launched during the Great Recession has caught hold is “really good involvement from the private sector.” It’s not academic and it’s not getting together for coffee and danishes once in a while and calling that an advisory committee, he says. “They advise the instructor and say, ‘You need to teach the 2026 version, this is where the industry is going,’ and our school adapts really quickly.”

Case in point: Arnett visited the company owner at aerospace manufacturer PMW Aero, who told him, “We do five-axis machining here. That’s all we do, but five-axis machining is not taught anywhere in South Carolina.”

“Jeromy has the position power,” says Farley, “to march into the school superintendent’s office, sit down and say, ‘Hey man, we have a company who needs five-axis machinists.’ ”

Within 30 days the community had pivoted like an expensive machining tool, sending teachers to Chicago to learn what they’d be teaching. “East of the Mississippi River, we have probably the only high school that teaches five-axis machining,” Farley says.

One Engineer’s Perspective

One Engineer’s Perspective

Three of the last six Scholar-Technicians® of the Year work at JR Automation, a Hitachi-owned company with operations at the commerce park. The company has 23 facilities across locations in Michigan, Utah, Tennessee and the Palmetto State, where the business unit relocated in 2011 and has since grown from a $30 million business to a $64 million business that was growing so fast it opened another unit close to Greenville Spartanburg International Airport. It specializes in custom industrial process automation and robotics solutions across a bevy of industries including life sciences — one of three areas of focus, alongside advanced energy and EVs, in the new strategic framework announced in January by the South Carolina Department of Commerce.

The 95,000-sq.-ft. shop floor at JR Automation is a study in pod-based innovation, as teams meticulously put together a vial-filling system for a leading global medical products company or a solution for an electronics manufacturer. Once a system is ready, the team will go install it at the customer’s site, sometimes staying for weeks or months depending on the scale of the build. Projects don’t so much unfold as tighten up across the facility, surrounded like the closely guarded secret solutions they are by sophisticated machinery and even more sophisticated expertise among the company’s more than 130 employees.

By email, I corresponded with one of those experts, Senior Controls Project Engineer Cord Sutter, whose experience sheds light on how talent migrates to a place like Pickens County. He grew up working on farms in rural western Michigan. “I also came from a family of educators, which had the result of exposing me at an early age to the idea that where a person comes from has no business deciding their aspirations for higher learning,” he wrote. He attended Lake Superior State University — “a place where I could balance my love for winter, hunting, fishing, and robots while pursuing my degree” — followed by internships in Michigan and Kansas and a job at Esys in Michigan. Esys was purchased by JR Automation, and having married in 2020, Sutter and his wife sought a change of pace that brought them to the company’s operation in Liberty.

“I recently celebrated my five-year work anniversary and enjoy a very satisfying work-life balance,” Sutter writes. “The job has never gotten stale and is always exciting. I appreciate the mixture of working from home, working from office and travel to customer sites …The mentors and talent pool here in Upstate South Carolina have blown me away and I am honored to work with such a distinguished team of professionals.”

The work JR performs has taken Sutter from granite slab processing in Texas to beverage cans in Virginia, candy bars in Pennsylvania and syringes in his new home state. That sort of collective experience offers a glimpse of the opportunity ahead for South Carolina.

“Because we work in such a broad array of industries, I have found that the automation industry is uniquely poised to bridge the technology gap between industry sectors,” he says. “I have personally seen the positive impacts when technology and tribal knowledge migrate from one discipline or industry to another, carried by our team members here at JR Automation. This accelerates the pace of advancement across the board for manufacturing, technology, and, in turn, education.”

Sutter sees excellent performance in STEM education in the region and thinks robotics is the key area to expand. “Every student with even the slightest inclination toward technology has their place in the world of robotics.”

Other employers in the commerce park rank globally in mission-critical niches such as aerospace ignitors and spark plugs, fire suppression equipment, capacitors and pacemakers.

“All of that stuff has a common denominator,” Farley says. “It has to work 100% of the time. The mindset of the Pickens County workforce is zero tolerance for defect. That mindset is promulgated through our schools and our technical high school. It’s part of the DNA here.”