In 1980 Intel made a bet on the Southwest. Forty years and $40 billion later, it’s still paying off for the global chipmaker and others today.

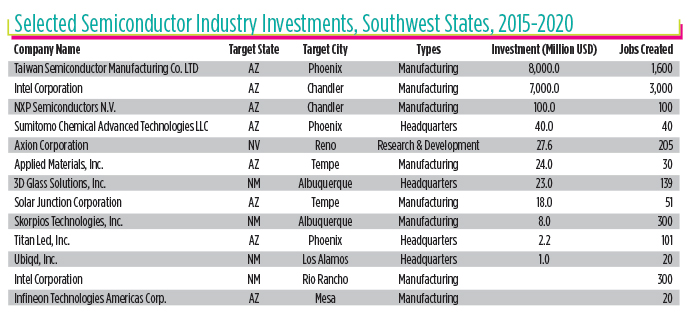

In the past five years alone, Site Selection’s Conway Projects Database has tracked more than $15.2 billion in corporate semiconductor and semiconductor machinery manufacturing investment in the U.S. Southwest, accounting for nearly 7,000 jobs.

Overall, Intel has invested more than $23 billion in Arizona, resulting in an annual economic impact of approximately $8.3 billion, based on 2018 data. The company had 12,000 employees in the state as of January 2020, working at Fab 6 in Chandler. And 3,000 more jobs are arriving thanks to one of the largest construction projects in the U.S.: Fab 42 at the company’s Ocotillo campus in Chandler, where 6,000 workers (10,000 at peak construction) were recently outfitting the fab with 1,300 tools and an overhead “highway” that zips silicon wafers around all four of the company’s Arizona factories.

In New Mexico, the 40 years has brought $16 billion in capital investment, an annual economic impact of $390 million and more than 1,800 jobs today at the company’s Rio Rancho site in Greater Albuquerque. The company’s ties include a strong connection to Sandia National Laboratories. Intel Federal LLC in October signed a three-year agreement with Sandia to explore the value of neuromorphic computing for scaled-up computational problems, which would eventually result in delivery of Intel’s largest neuromorphic research system to date, which could exceed more than 1 billion neurons in computational capacity.

“The goal is to apply the latest insights from neuroscience to create chips that function less like traditional computers and more like the human brain,” Intel explains. “Intel sees its Loihi research chip and future neuromorphic processors defining a new model of programmable computing to serve the world’s rising demand for pervasive, intelligent devices.”

Chip Growth Medium: Water, Talent and … Incentives?

But wait: Doesn’t making chips require a ton of water? Yes, it does, to the tune of between 2 million and 4 million gallons of ultra-pure water a day. But Intel has done its part in the desert.

“The Southwest is grappling with the multipronged threat of extended drought, climate change and overallocation,” wrote Intel CEO Bob Swan in an October 2020 column celebrating National Manufacturing Day and the company’s 40-year anniversary in Arizona. “Effectively managing water supply is essential to the state’s continued growth and economic security. To date, Intel has funded a dozen water restoration projects with nonprofits estimated to restore roughly 800 million gallons of water per year to support Arizona’s supply. And our new Fab 42 features our most ambitious on-site water recycling facility that, once complete, will be able to treat more than 9 million gallons of water each day.”

Even as it reduces its draws on the water table, Intel is enriching its pools of talent.

“This year, we helped Maricopa County Community College District launch the first Intel-designed artificial intelligence (AI) associate degree program in the United States,” wrote Swan.

He noted Arizona’s success in attracting other manufacturers. Those include Taiwan Semiconductor’s recently announced $12 billion fab, and a new gallium nitride plant in Chandler from NXP Semiconductors whose products will help power 5G cellular infrastructure expansion. Swan said Intel is “encouraged by bipartisan efforts at the federal level to increase semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S. Advancements in silicon technology will give the U.S. access to breakthrough capabilities.”

In a companion piece to Swan’s column, Jeff Rittener, Intel’s chief government affairs office and general manager of governments, markets and trade, laid out the reasons why it’s important to grow chip manufacturing.

“On this Manufacturing Day, we find ourselves at a crossroads,” he wrote. “Eighty percent of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity is now in Asia. Intel and the entire U.S. semiconductor industry face fierce competition in the global semiconductor marketplace. The U.S. risks falling behind in an industry it once dominated and that its economy and national security depend on.”

A new joint study by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) and Boston Consulting Group (BCG) analyzes the impact of proposed federal incentives on domestic semiconductor manufacturing, finding that such incentives would “reverse the decades-long trajectory of declining chip production in America and add many new major semiconductor manufacturing facilities as well as thousands of high-paying jobs in the U.S. over the next 10 years,” the SIA says.

Time to Reverse the Trend

I participated in a virtual panel discussion about the report in early October, where Antonio Varas, senior partner and managing director at BCG, explained that the U.S. dominates with a 45% share of semiconductor sales globall. But the country has only a 12% share of semiconductor manufacturing, unlike other industries considered strategic for the U.S. economy — the global share in manufacturing is 49% in aerospace, 25% in medical equipment and 23% in pharmaceuticals.

“This has not always been the case,” Varas said. “The 12% we see today is the result of a long trend of decline in the last 30 years. In 1990, the U.S. accounted for 37%. In parallel to that decline, the share of Asian countries (Korea, Taiwan and China) has been growing” as they made semiconductor manufacturing a national priority. If the current trend holds, Varas said, “We would expect a decline to 10% by the end of this decade. China, on the back of an aggressive investment policy, could emerge as the number one location with 24%.”

In addition to maintaining U.S. leadership in the industry, “it should be obvious that having more than 75% of global capacity in a small area like East Asia poses a question of supply chain resilience, in particular because this region is exposed to natural disasters, and in the last few years, highly exposed to geopolitical frictions,” Varas said. Of course, its relationship with the U.S. is the primary friction point.

Essentially the U.S. is well positioned in terms of access to talent and security of IP and assets, but not in labor costs or government incentives. So BCG built a model illustrating the total cost of ownership for three types of fabs.

The U.S. government offers the lowest level of incentives, with Taiwan, Korea and Singapore offering double and China offering the highest. Taking everything into account, “the cost of building and running a fab in the U.S. is about 25% higher than if you run a fab in Taiwan, South Korea or Singapore, and 50% more than in China,” he said. That means 40% to 70% of the extra cost in the U.S. comes from lack of incentives. “Incentives have a very material role in the perceived lack of competitiveness,” he said.

“What would happen if the U.S. no longer made planes or spacecraft?” asked Greg S. Slater, vice president and manager of Intel’s policy and technical affairs organization. “Actually, semiconductors underlie both of those industries. They are foundational building blocks for the digital economy and for a lot of other industries in terms of automation, digitization and being more productive.

“Intel put in $29 billion in capex and R&D last year,” he said. “We are one of the most capital-intensive industries around, and we are the fifth-largest spender in the world on R&D. A majority of our manufacturing is in the U.S., but we could have more in the U.S. if we close that gap. If a grant maxes out at $3 billion per project, that would close perhaps 5% to 7% of the cost difference. It’s going to help, but not level the playing field. That’s why we also need an investment tax credit.”

Slater said the average salary in the industry is around $150,000 a year in total compensation. A new federal incentive, he said, would do a lot more than just prevent the continued erosion of manufacturing market share.

“It’s also the jobs,” he said. “It’s the value added to our increased productivity from manufacturing leading-edge products. And the military leadership, which relies more and more on automated weapons. At the cores of those weapons are semiconductors.”

Should the nation’s leaders wake up to the value of the industry, the U.S. Southwest is poised to reap the benefits.

“As we know well, Arizona is a great place to build the future, and we’re honored to have paved the way,” Intel CEO Bob Swan wrote in October. “Forty years from now, how and what Intel manufactures may look quite different. But what won’t change is our belief in the power of technology to enrich lives and our relentless effort to provide the technology foundation for the world’s innovation.”