Farm work is not for the faint of heart. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, agricultural workers suffer up to five times as many deaths as those in all other industries. That’s where the University of Washington’s Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center comes in.

Founded in 1996, PNASH (think “panache”) conducts applied research into agricultural safety as it promotes best practices in farming, fishing and forestry in the Pacific Northwest. Combined, those sectors employ 164,000 Washingtonians.

“Our mission is built around precision agriculture technology on the farm and injecting safety into that,” says Eddie Kasner, the Center’s director of outreach.

Consider forestry, an occupation that employs more than 40,000 workers in Washington state. It’s dangerous work, with job tasks involving chainsaws, heavy lifting and falling and burning trees. One of PNASH’s current projects involves developing a smartwatch app for loggers.

“We’re looking to reduce injuries among a group of workers that is out there performing high-risk work in remote areas,” says Kasner. Through the app, he says, “You’ll know where everybody is before you fell a tree. It can send alerts to loggers and, if a logger stops moving, alert someone else to go check on them.”

Currently one of 12 agricultural research centers funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, PNASH has ongoing projects to assess respiratory hazards to cannabis industry workers; reduce potentially harmful drift from pesticide sprayers; and develop less intrusive life jackets to promote their more widespread adoption on fishing boats. Fish and seafood are the state’s top agricultural exports.

Emphasizing as it does practical solutions, the Center, says Kasner, also awards grants to employers and community-based organizations to put its research into practice.

“Engagement with the community is a big part of our mission,” he says. “We’re finding practical solutions for both employers and workers.”

A Robust Partnership

PNASH is but one example of how state universities, the federal government and private enterprises work together in Washington on emerging agricultural products, production techniques, health advocacy and sustainability. In August, federal officials joined state lawmakers and leaders at Washington State University to break ground on a new U.S. Department of Agriculture Plant Sciences Building on WSU’s Pullman campus. The facility, supported by nearly $125 million in federal funding, is to open in 2025.

The collaboration between WSU and the U.S. Agricultural Research Service (ARS) dates back to 1931 and, according to the USDA, is “one of the nation’s most robust federal-state partnerships.” On hand for the groundbreaking, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said the Plant Sciences project “opens a new era” for the long-time alliance.

“We have a university and a government research entity in partnership, ensuring that farmers, ranchers, growers and producers can continue to be productive. Each one of us,” said Vilsack, “should be thankful for the science that’ll take place here.”

Washington leads the nation in apple production.

Photo: Getty Images/ Mariloutrias

Research conducted at the facility is to focus on improving the health, sustainability and profitability of dryland and irrigated agriculture in the Northwest. Being built from the ground up, the building will house scientists from WSU and ARS. Members of the WSU Departments of Plant Pathology, Crop, Soil Sciences, and Horticulture will share lab and office space with federal researchers from ARS Departments of Plant Pathology, Crop, Soil Sciences, and Horticulture.

“This building,” said Elizabeth Chilton, chancellor of the WSU Pullman campus, “will support faculty members, students and researchers partnering together to create better crops and more sustainable farming practices so that we’re able to better feed our planet. The groundbreaking research that this facility will support will literally change lives.”

Fields of Plenty

Washington’s agriculture industry is worth an estimated $49 billion, employs 164,000 people and accounts for 13% of the state’s economy. A varied climate and geography, the latter defined by the Cascade Range, supports 300 different crops across 15 million acres of farmland.

“The state’s diverse geography,” according to the Washington State Department of Commerce, “combines with ocean-fueled microclimates to create an endless variety of growing regions, from the moist hillsides and valleys on the west side of the state to the fertile, rolling plains of Eastern Washington.

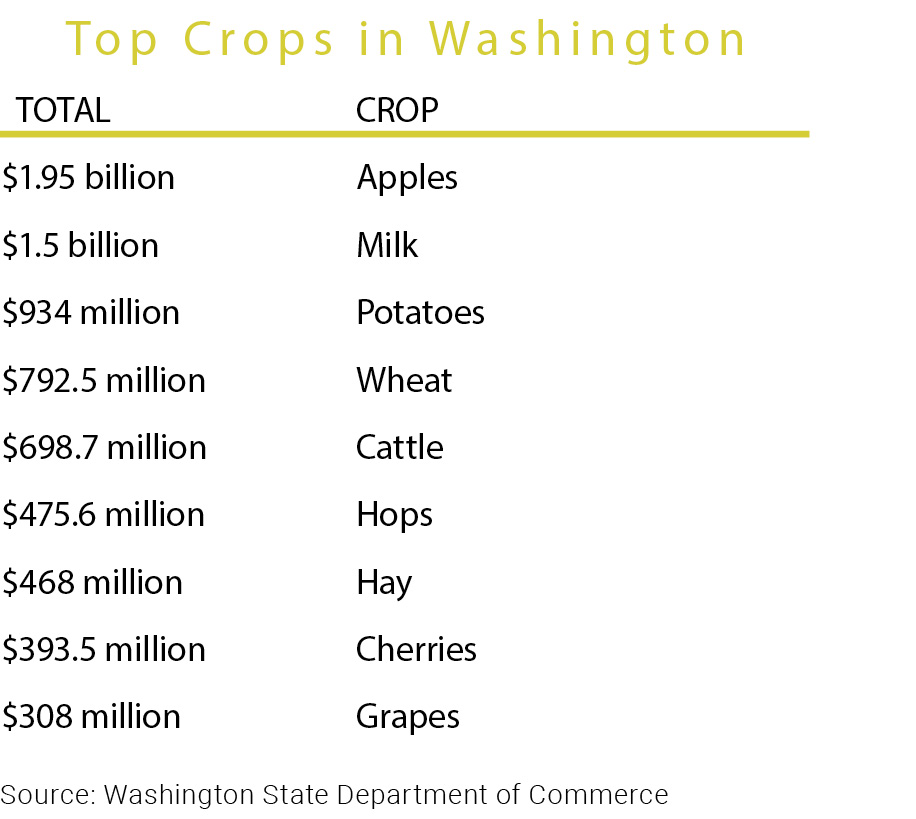

Apples, a $1.95 billion industry, are Washington’s top crop. Washington produces more apples — Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Honeycrisp, Fuji, Granny Smith, Gala, Jonagold and Braeburn among them — than any other state.

Oysters raised in Washington

Photo: Getty Images/ Larry Zhou

Washington is also the top state for production of blueberries, hops, pears and sweet cherries, and is the second largest U.S. producer of apricots, asparagus, grapes, potatoes and raspberries. The state’s hundreds of farm commodities range from bison, beets and broccoli to turkeys, tomatoes and turnips. Of the 36,000 farms that drive the state’s agricultural sector, two-thirds measure less than 50 acres, and 96% are family rather than corporately owned.

A Bounty for Business and Entrepreneurs

A Bounty for Business and Entrepreneurs

Food processing is a $12 billion business and Washington’s second-largest manufacturing industry. The state offers an array of incentives to promote value-added agriculture, including tax exemptions and deductions for manufacturers of fresh fruit and vegetable crops.

Through a series of recent expansions, Oregon-based Reser has invested more than $120 million to boost its 25-year potato salad operation in Pasco, west of Walla Walla. Seattle-based Darigold, a farmer-based dairy co-op, is in the midst of its third major capital project in as many years — a $600 million milk production facility, also in Pasco.

Opportunities abound for entrepreneurs, as well. Ask Cisco Navvarete, founder of PNW Fresh Clams and Oysters, established in Shelton in 2019. Through a recent agreement with the Nisqually tribe, Navvarete is reinvigorating a 76-acre oyster farm on Puget Sound’s Henderson Inlet. Now 28, the first-generation American of parents born in Mexico began as an oysterman for Seattle’s Taylor Shellfish Farms then branched out into brokering.

“I got pretty good at it, and I felt comfortable enough to go the next step,” he says, “which was trying to find a lease to do it all myself, from seedlings to market-size oysters.”

His plan, he says, is “to put a million oysters out there.” Right now, there are about 10,000. No sweat, though, for Navvarete is accustomed to uphill battles.

“I come from a migrant worker background, and success has not been part of my environment. So, my idea of success is to be able to give opportunities to my kids, give them resources and a better future. I’d like to be independent. That’s what success is to me.”