“Postdoctoral scholars form the backbone of the global biomedical research enterprise.”

With that assertion, a team led by Tammy Collins, Ph.D., director of the Office of Fellows’ Career Development at the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, set out to document detailed career outcomes for more than 900 NIEHS postdoctoral fellows, or postdocs, over the past 15 years. (Postdocs are scientists who have received their doctoral degrees and are participating in a program that offers additional training.)

Lead author and NIEHS computer scientist Hong Xu analyzed the data using the R Project for Statistical Computing, a free online program that displays data using graphs and charts. Shyamal Peddada, Ph.D., former NIEHS head of the Biostatistics and Computational Biology Branch, served as key advisor. The study appeared online in the journal Nature Biotechnology, and is the first standardized method for categorizing career outcomes of NIEHS postdocs.

The new tool still emerging from their findings separates employment trends in biomedical science by sector, type, and job specifics. What they found out a) reflects similar clustering in the private-sector life sciences community, and b) may offer guideposts for talent migration more broadly that those biomedical companies would do well to heed.

"As we sought to determine how to make sense of detailed career outcomes in a standardized way, we used a bottom-up approach, rather than forcing the data into any particular naming system already being employed," Collins said. "We looked at what our postdocs were specifically doing, and asked, ‘What is the most logical way to categorize and visualize the information?’ "

Among the findings:

- Ninety-one percent of US scholars remain in the US (415/455), while only 45 percent of international fellows (198/436) do.

- About two-thirds of alumni from China and India remained in the US, while only about one-fifth of alumni from Japan and South Korea remained, with most returning home.

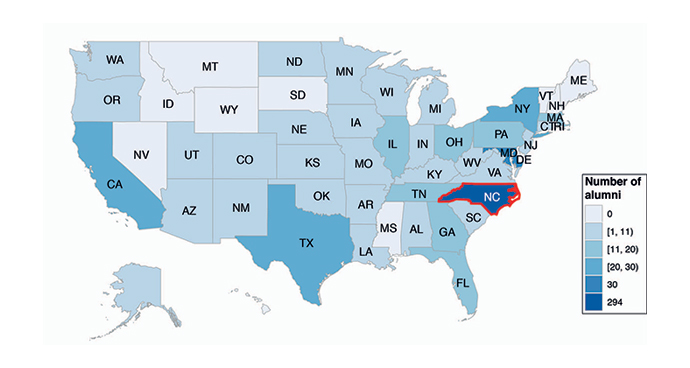

- One-third of all NIEHS alumni remained in North Carolina (294/891), the location of NIEHS. "This trend is not surprising given that other studies show that individuals tend to settle near the areas where they receive training," write the authors. The next highest concentration of fellows included those in the Maryland/DC metro area, with the rest distributed across the US in a manner approximately proportional to state populations.

- Significantly more US scholars were employed within for-profit companies in professional positions conducting applied research, while international scholars obtained academic tenure-track faculty positions conducting basic research at nearly twice the rate of US scholars.

In an almost 2-to-1 ratio, international postdocs were going into academic positions to do basic research. However, analysis of the total number of international postdocs specifically entering academic positions showed that 70 percent of this subpopulation entered them abroad. US postdocs tended to enter for-profit companies to do applied research.

The careers project began in 2013 as a way to establish a snapshot of career trajectories for NIEHS postdocs and to report the findings to NIH. Other institutions have since committed to similar efforts. Work at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) revealed in 2014 that 62 percent of more than 1,700 postdocs who stayed in research careers since their separations from UCSF from 2000 to 2013 had stayed in academia, with 19 percent going into industry. (Nine percent of those not engaged in pure research careers were still in science-driven careers, such as biotech business development or clinical work.)

| Region | Number of Alumni |

|---|---|

| North Carolina | 294 |

| Maryland | 30 |

| New York | 24 |

| Texas | 22 |

| California | 21 |

| District Of Columbia | 20 |

| Illinois | 19 |

| Pennsylvania | 18 |

| Massachusetts | 14 |

| Florida | 13 |

| Ohio | 13 |

| Georgia | 11 |

| Tennessee | 11 |

| New Jersey | 8 |

| South Carolina | 8 |

| Connecticut | 6 |

| Indiana | 6 |

| Virginia | 6 |

| Kentucky | 5 |

| Michigan | 5 |

| North Dakota | 5 |

| Arkansas | 4 |

| Colorado | 4 |

| Louisiana | 4 |

| Minnesota | 4 |

| Nebraska | 4 |

| Unknown | 4 |

| Washington | 4 |

| Wisconsin | 4 |

| Alabama | 3 |

| Arizona | 3 |

| Iowa | 3 |

| Oregon | 3 |

| New Mexico | 2 |

| Utah | 2 |

| Alaska | 1 |

| Kansas | 1 |

| Missouri | 1 |

| Oklahoma | 1 |

| Virgin Islands | 1 |

| West Virginia | 1 |

| Delaware | 0 |

| Hawaii | 0 |

| Idaho | 0 |

| Maine | 0 |

| Mississippi | 0 |

| Montana | 0 |

| Nevada | 0 |

| New Hampshire | 0 |

| Rhode Island | 0 |

| South Dakota | 0 |

| Vermont | 0 |

| Wyoming | 0 |

The focus of the UCSF analysis was primarily internal to the academic institutional realm, i.e. how to sustain careers, treat tenure and do the best science in institutions. But it largely glossed over a significant finding: By 2016 that percentage in private industry had risen to nearly 25 percent.

That’s in part because the tradition of tenure is fading. As the authors write in their paper, "Postdoctoral scholars are highly skilled scientists that, classically, have been trained to enter into academic tenure-track positions. However, the number of these tenure-track positions is remaining largely flat while the number of postdoctoral fellows is increasing, meaning that the majority of scientists will obtain other types of careers."

Among the jobs NIEHS alumni hold were positions ranging from professors at academic institutions around the world to scientists at such firms as Novartis, KBI Pharma, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb and Kaiser Permanente, to one self-employed textile artist.

RTP’s Magnetic Pull

In an interview, Dr. Collins says that, in addition to providing information to prospective graduate and postdoc students, "We felt location was also an important thing to look at." What they found was that a lot of people stay in the environment where they’ve completed their training, e.g. Stanford people like to stick around Stanford. So it’s not a total surprise that many postdocs from the North Carolina–based NIEHS stay in the Tarheel State.

"Of the people who stay in the US, half stay in North Carolina, and most of them are staying in the Research Triangle Park area," says Collins, a native of Rocky Mount herself, who attended Duke University as a graduate student. "For those going into the for-profit sector, they tend to stay in the area," she says, while the academics tend to be more mobile. Many postdocs also are in the stage of their lives when they are starting families: She says about half of those studied who were in that stage of their lives and careers chose to stay in the RTP area.

Collins and Xu are refining a way to visualize data using the R software, and plan to release additional information on NIEHS career outcomes online. Releasing the information to the public would allow individuals or institutions to upload data from an excel spreadsheet into the new tool and readily see and compare their own employment trends.

As more biomedical research is sponsored or pursued on academic campuses, even as her team has created this career taxonomy, does Collins see traditional academic/government/corporate lines blurring when it comes to R&D careers?

"I would definitely say so," she responds, noting a regional consortium that conducts site visits to companies in order to showcase career opportunities. "My husband went to UNC-Chapel Hill, did a joint fellowship between UNC and GSK, and spent a year in a pharmacy lab and then a year in the industry lab. But in addition to that, in graduate education in general there is an increase in internship opportunities for graduate-level students. I’m seeing a lot more of those pop up, where they rotate into companies, for instance. We really see blurring between all the different sectors."

Among topics for further study is career outcome differences between US and international alumni in future work, "especially in light of studies suggesting that migration has a positive effect on scientific performance," say the authors, before using scientific language with a genetics tint to describe how such knowledge workers may evolve: "This effect is predicted to result from the knowledge recombination gained from migration."

In other words: Travel is good for you.

"There could be a number of factors," Collins says. "But the hypothesis is this: Training in one country where there is a certain way of doing things, then going somewhere else and having a diverse set of experiences, potentially makes your science better."