“Today, the growth in commercial space transportation is more and more noticeable to the American public.”

So said Michael Huerta, administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration, on May 15 at a meeting of the Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC) in the nation’s capital.

But as any business knows, reaching stratospheric heights — metaphorically or literally — requires a safe place to launch.

The American public may be familiar with the two most heavily used U.S. government-owned launch complexes: Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida (located on the same piece of land as NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, from where the Space Shuttle launched) and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

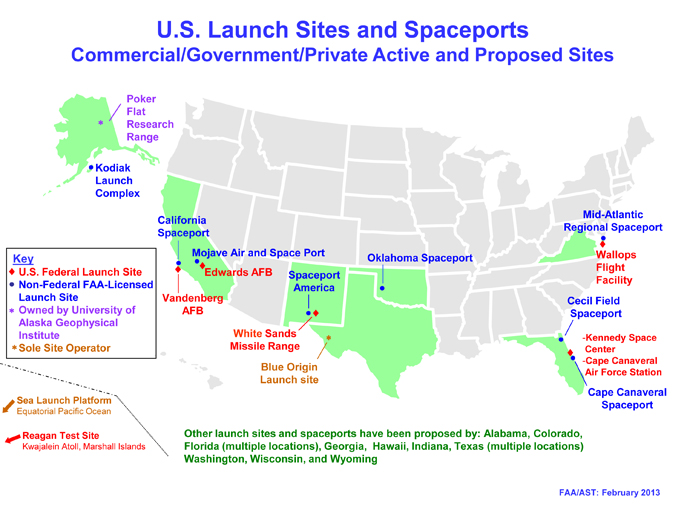

But do you know where the eight non-federal commercial launch facilities are?

Okay, we’ll provide the answers (and even a helpful map below):

- California Spaceport at Vandenberg Air Force Base

- Spaceport Florida at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

- Cecil Field Spaceport, Jacksonville, Fla.

- Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport at Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia

- Mojave Air and Space Port in California

- Kodiak Launch Complex on Kodiak Island, Alaska

- Oklahoma Spaceport, Burns Flat, Okla.

- Spaceport America, Las Cruces, N.M.

Where in the rest of the world can you go launch? The very helpful Space Launch Report informs us that as of July 19 this year, the global distribution of launches looks like this:

| YEAR TO DATE LAUNCH SITE SUMMARY | |

| Site Overall Launches (failures) | |

| Baikonur, Kazakhstan | 13(1) |

| Cape Canaveral, Florida | 6(0) |

| Kourou, French Guyana | 4(0) |

| Plesetsk, Russia | 3(0) |

| Jiuquan, China | 3(0) |

| Vandenberg AFB, California | 2(0) |

| Sriharikota, India | 2(0) |

| Tanegashima, Japan | 1(0) |

| Taiyaun, China | 1(0) |

| Wallops Island, Virginia | 1(0) |

| XiChang, China | 1(0) |

| Naro Space Center, South Korea | 1(0) |

| Odyssey LP, Pacific Ocean | 1(1) |

| Taiyaun, China | 1(0) |

Meanwhile, development of capabilities and clustering of companies involved in the burgeoning field of space travel continues to proceed apace at many of the U.S. sites. And indeed, as Huerta explained in May, their work is being noticed.

In 2012, SpaceX completed its Commercial Orbital Transportation Services demonstration mission by launching and berthing its cargo capsule to the International Space Station, then safely returning with cargo intact back to Earth. It was the first time that private industry resupplied the Space Station. Since that time, SpaceX has completed two more cargo missions. And the company has been operating in McGregor, Texas, under an experimental permit from the FAA to use the Grasshopper rocket to conduct a launch and then return to a vertical position on the launch pad. That work is now transitioning to New Mexico. The company already has more than 3,000 employees in California, Texas, Washington D.C., and Florida.

Other locations supporting the industry with manufacturing, assembly and testing are quietly ramping up too. Just this week, the Centennial, Colo.-based United Launch Alliance — comprising the Atlas and Delta teams from Lockheed Martin and Boeing — announced that during the last eight days its team has completed five major processing activities, including one launch, on three different launch pads at Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg. ULA program management, engineering, test and mission support functions are headquartered in Denver, Colo. Manufacturing, assembly and integration operations are located in Decature, Ala., and Harlingen, Texas.

In Florida in May, aerospace-related propellant services provider United Paradyne Corp. announced it is expanding to Kennedy Space Center as it seeks to broaden its capabilities with government and commercial launch providers and expand its research and development operations. The State of Florida and Enterprise Florida joined the EDC of Florida’s Space Coast, Kennedy Space Center, Space Florida, Brevard Workforce and the Brevard County Board of County Commissioners as integral partners in the UPC project. UPC’s return to the space center, where the California-based company served as a propellant subcontractor from 1998 to 2008, will create at least 50 jobs over the next four years with average annual salaries of $64,000. The company’s capital investment over that time will exceed $9 million.

“There is no doubt that Kennedy Space Center, even after the shuttle has stopped flying, remains an amazing asset for our economy,” said EDC President and CEO Lynda Weatherman. “It is an iconic facility known around the world, and with this powerful coalition of the EDC, the Center Planning & Development team, Enterprise Florida, Space Florida and others, we are working to ensure it will continue to meet the needs of commercial companies who are rightfully excited about locating there.”

Orbital Sciences demonstrated its launch capabilities in April 2013 for the same service, taking off from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport on Wallops Island, Va. And Virgin Galactic has begun powered test flights of its Space Ship Two design, in an effort to begin flying tourists from Spaceport America in New Mexico.

So far, just seven individuals have paid many millions to be space tourists, beginning with entrepreneur Dennis Tito in 2001 and featuring Cirque du Soleil’s Guy Laliberte most recently in 2009. But more than 600 individuals have been willing to commit $200,000 to a ticket on a future Virgin Galactic flight, which will propel passengers 62 miles above the earth.

As Huerta explained in his speech, XCOR Aerospace has begun advertising the capability of its Lynx spacecraft to take people and payloads on a half-hour suborbital flight. Boeing, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX continue to work on their own designs for a commercial crew vehicle to take astronauts to the International Space Station. And Bigelow Aerospace is working toward giving spaceflight participants new destinations in orbit.

Thirty years ago there was no commercial space transportation industry. By 2009, U.S. commercial space transportation and the services and industries it enables accounted for more than $208 billion in economic activity, says the FAA. Over one million people were employed as a result of these activities. This level is likely to grow in the future as new applications dependent on commercial space transportation emerge.

“The goal of lowering the cost for access to space is noble, not only for business, but also for science and the accessibility of space to more people,” said Huerta. “As with space itself, the possibilities are endless, and they are not limited to a few locations or a handful of companies. The FAA has licensed spaceports in Mojave, California, in Kodiak, Alaska, and in several other locations. There is also interest in developing other launch facilities in Florida, Texas, and Colorado, to name just a few.”

There have been a total of over 200 U.S. commercial launches licensed since 1989 with no loss of life or serious injury or property damage to the public, and the level of launch activity is increasing rapidly.

Prepare the Way

Measures to support the industry are increasingly rapidly as well. Last September the FAA awarded nearly $500,000 in new Space Transportation Infrastructure matching grants to three projects located in California, Colorado and Hawaii that will help develop and expand commercial space transportation infrastructure, including feasibility analysis for launch sites in Hawaii and Colorado, and safety equipment for California’s Mojave Spaceport.

In February 2012, for example, Florida Gov. Rick Scott signed a Space Florida infrastructure bill that redefined launch facilities to encompass related assembly and processing facilities in addition to control centers and launch pads, thus ensuring that state transportation department funds could be used to support necessary infrastructure improvements at Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral.

In April this year, New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez signed legislation expanding existing liability protections for spaceflight operators to spaceflight manufacturers and suppliers. The New Mexico Expanded Space Flight Informed Consent Act prevents lawsuit abuse and addresses the inherent risks of space flight. California is pursuing similar legislation.

“We are not only reaffirming the major commitment New Mexicans have made to Spaceport America but we now have an even stronger opportunity to grow the number of commercial space jobs at the spaceport and across our state,” said Gov. Martinez.

Building on existing legislation passed in 2010, which covered only spaceflight operators like Virgin Galactic, the new law provides coverage to both operators and their supply chain during the critical early years of the industry’s development. The enhancement, which costs taxpayers nothing, still allows legal options for spaceflight participants in cases of willful, wanton or reckless disregard, while creating an environment that enables New Mexico to more successfully recruit and retain commercial space tenants and customers for human spaceflight operations at Spaceport America.

“The passage of this expanded liability protection is extremely important to the future of New Mexico’s leadership position in the commercial space industry, and demonstrates the appreciation and strong support by our Governor for the cutting edge space technology and the associated jobs that will come to our state.” said NMSA Executive Director Christine Anderson. “With this protection enacted, NMSA is now ready and able to get back to the business of building the commercial space industry here in New Mexico. I would like to also emphasize that Spaceport America is open for business.”

Spaceport America has already created over 1,100 construction jobs in New Mexico and has hosted 20-plus launches, including UP Aerospace on June 21. NMSA also is now generating consistent revenues for the State of New Mexico following the commencement of rent on the 20-year lease of the spaceport’s main terminal hangar facility, signed with Virgin Galactic in 2008. Virgin last year opened a support office in Las Cruces, N.M., as well.

NMSA continues to work closely with leading aerospace firms such as Virgin Galactic, SpaceX, Armadillo Aerospace, Lockheed Martin, Moog-FTS, and UP Aerospace and their customers NASA and the Department of Defense. SpaceX in May signed a three-year agreement to lease land and facilities at Spaceport America to conduct the next phase of flight testing for its reusable rocket program.

A Leader’s Perspective

Anderson was the founding director of the Space Vehicles Directorate at the Air Force Research Laboratory, Kirtland Air Force Base. She also served as the director of the Military Satellite Communications Joint Program Office at the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles, where she directed the development, acquisition and execution of a $50-billion portfolio.

“It’s a very pivotal time,” she says in an interview. “NASA retired the Shuttle, so you’re seeing Space X step in flying cargo to the space station. A number of companies are vying for the commercial passenger space line. It’s an opening up of the industry, and we’re fortunate enough to be the first purpose-built commercial spaceport.”

The launch complex is situated on 18,000 acres adjacent to the U.S. Army White Sands Missile Range in southern New Mexico, and has been providing commercial vertical launch services since 2006. Anderson says it’s an opportunity of a lifetime to see the non-metaphorical launch of an entire industry, whether the missions involve scientific research, cargo delivery, colonization or even resource mining from other planets.

On the industry side, there are supply chain jobs related to Space X and its Grasshopper testing. But just as central to NMSA’s mission is the education and tourism component. Start with the difference between a spaceport and an airport:

“When I go to an airport, I don’t plan to have fun,” quips Anderson. But central to her team’s mission in New Mexico is to educate the public, and make it “a fun place to come watch launches and learn about space.”

Among other things, she says, the complex will want to be ready to offer amenities to the friends and families of those 600 people on Virgin’s space tourist list. A visitor’s center is projected for completion sometime in late summer 2014. Anderson says a conservative estimate projects 200,000 visitors a year, including many from outside the United States. Visitors already come anyway, including monthly media tours featuring news outlets from Taiwan, South America and Sweden, among others.

“We’re owned by the State of New Mexico, and took state bond money, but my charter is to be totally self-supporting,” says Anderson. “I don’t know how fast commercial space is going to mature, to the point of point-to-point travel. I know from my military experience that space travel is very hard. My goal is to be self-supporting and make enough money to roll back in to keep the spaceport maintained, and make the experience current and vibrant.”

Anderson wasn’t in her current post when the site was picked, but says the primary reason was its positioning on the backside of the missile range, where airspace is already restricted and there are thousands of acres of land.

“To be an inland space port, you needed that,” she says, pointing out that others are on oceans. “It is very unique space. There are only two restricted airspaces that large, and the other one is in D.C.”

Anderson says it’s an interesting juxtaposition of the Wild West frontier and the new frontier beyond the clouds, with two cattle ranches on site and a Ted Turner buffalo ranch just to the north. There are layers of history too, with 21 NEPA-identified archaeological sites on the property, and parts of the El Camino Real winding in and out. The railroad came through in the 1880s, and now BNSF operates a line just outside NMSA property.

Anderson says all but $20 million of NMSA’s allotted total of $213 million is spent or encumbered on contracts involving the 12,000-by-200-ft. runway (or “spaceway”), the dome-shaped spaceport operations center and other fitting-out obligations. Meanwhile, the launches and payloads continue to come and go: Celestus has carried human remains into space and safely returned them to be re-interred. And student and scientific payloads continue to line up.

Anderson equates this period to the pioneer period of air travel.

“When you’re making history, people don’t appreciate it,” she says. “But 50 years from now, people may look back and say it’s like Orville and Wilbur Wright.”