If you listened to every company’s pitch at the annual Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, you’d emerge thinking you’d just visited an alternate universe, flying through a utopian dream of the future before landing with a thud on the pavement of everyday life.

Then again, Las Vegas tourists have that feeling every day.

For one of those companies, however, the time is now. The place is just up the road in North Las Vegas. The wager encompasses a whole lot more than just putting on a show. And when it’s placed in the context of other corporate investments in Nevada, ecosystem seems too mild a term. We may be witnessing the birth of a mobility solar system.

On December 10 at the CES, Faraday Future Vice President of Global Manufacturing Dag Reckhorn joined Nevada Governor Brian Sandoval and Governor’s Office of Economic Development Director Steve Hill to announce the company had selected Apex Industrial Park in North Las Vegas for a $1-billion, 3-million-sq.-ft. (278,700-sq.-m.) electric vehicle production complex that could create as many as 4,500 jobs over the next seven years building sleek, high-performance vehicles.

“We are eager to begin production of our vehicle of the future — it will embrace the increasingly intrinsic relationship between technology and mobility,” said Reckhorn.

Five days later, Sandoval convened a special session to consider the deal’s incentive package, and on Dec. 21, he signed those incentives into law. “The passage of the legislation today signifies a new chapter for the economic opportunities of southern Nevada. I am grateful for the opportunity to work with the City of North Las Vegas, Clark County and all interested parties and stakeholders to take a large step forward in diversifying the southern Nevada economy,” said Sandoval, who presided over the plant’s groundbreaking in April.

Region Robust with Resonant Projects

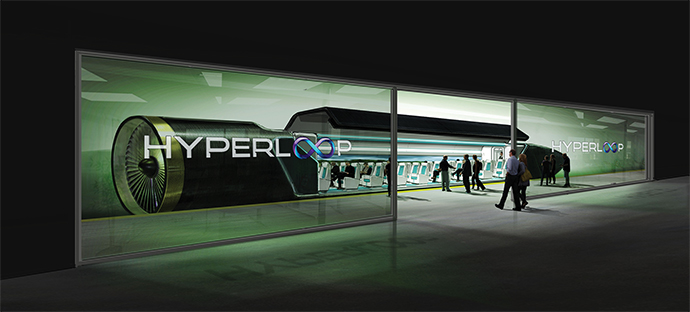

By coincidence or fate, two days before the Faraday announcement, another Elon Musk dream-in-the-making — the Hyperloop Technologies high-speed transport project — had committed to a parcel in the same Apex Industrial Park. A pilot buildout of Hyperloop’s nearly frictionless pods, designed to one-day travel at ultra-speed through tubes between Los Angeles and Las Vegas and up and down the California coasts, began testing there early this year.

Northern Nevada already has its futuristic billion-dollar baby, in the form of Tesla’s battery gigafactory. That project could involve up to $10 billion of investment by Tesla, and attracted its own $1.3-billion incentive package.

Meanwhile, it’s really not that far to Tesla’s own automotive plant in Northern California, or to electric bus maker Proterra’s new HQ in Burlingame.

Faraday Future, based in Gardena, California, is largely backed by Chinese billionaire Jia Yueting, founder and chairman of Leshi Television and of global technology firm LeEco, which is partnering with Faraday on an autonomous driving research center, LeFuture AI Institute, to be located at the new LeEco North American headquarters campus that broke ground in San Jose, California, in late April. Faraday also happens to employ a number of former leaders at Tesla, its avowed rival. It received California regulatory approval for road testing earlier this year. Meanwhile, In May, the Nevada Governor’s Office of Economic Development (GOED) and the Nevada Institute for Autonomous Systems (NIAS) executed a teaming agreement with EHang, Inc., a Chinese developer and maker of unmanned aerial vehicles, that will provide the foundation for collaboration in the areas of flight testing, training, and development at Nevada’s FAA UAS Test Site, located at Ren-Stead Airport.

How It Unfolded

Consultants at Cushman & Wakefield Strategic Consulting who led Faraday’s site selection process for “Project Robin” say they were completely unaware of the parallel choice of Apex by Hyperloop, as negotiators on the other side of the table abided by non-disclosure agreements. The consultancy led site selection and incentives negotiations for the Faraday project, completing the property search, labor market due diligence, financial evaluations and incentive negotiations over a 10-month period. The team was led by Andy Mace and Alexander Frei, heads of specialty practices within the firm’s Strategic Consulting practice, with a major assist from Keith Gendreau, project manager for the site selection.

In a group interview earlier this year for The Site Selection Energy Report, Mace, Gendreau and Frei said the project came their way through a series of automotive industry referrals via their Detroit office. In collaboration with Faraday Future, Cushman & Wakefield’s team evaluated over 100 properties, both brownfield and greenfield, in 10 US states and portions of Mexico, weighing expected human resources costs and labor availability, access to supplier and customer markets, real estate and infrastructure suitability and incentives.

“The client had a very broad search area and set of possibilities,” said Mace. Three filters were used to whittle down the geography: 1) existing automotive production and supplier corridors in the two countries; 2) availability of large, existing automotive plants or buildings; and 3) leaning toward California and the western US, in order to be near the company’s targeted talent and headquarters base in Southern California.

Northern Mexico was in the mix, but Mace said consideration of Mexico did not proceed to a very advanced level. Asked if there was concern due to the number of other big automotive projects that already have landed there, he said, “At no time were we concerned about Mexico’s labor availability for this.”

A compressed time frame pushed the process through several iterations, said Gendreau, as the team performed extensive cost comparisons and studied site availability in the Western US and Mexico initially, then was asked by Faraday to expand the search area to include the southeastern US and other corridors.

“That process evolved into a several-month site selection effort,” said Gendreau, from March to September 2015. The 10 states in the running: Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, South Carolina, Georgia, California and Nevada.

“We evaluated hundreds of properties,” Gendreau said, focusing on existing large-scale, automotive-related buildings. Soon the short list was down to eight sites that were featured on a tour of Louisiana, parts of Georgia, Texas, Arizona, Nevada and California. Labor market evaluation and employer interviews followed, along with detailed cost comparisons, “and incentives were kicked into high gear at that point,” he said.

Good Size, Clear Air

The North Las Vegas property fared well on many site attributes, so was an early top contender, especially given Faraday’s desired proximity to the Western US. Other finalists were located in Georgia, Louisiana and California. While other sites were ready to go, the Nevada site needed some work, Frei said, as reflected in the project’s ultimate incentive package.

Soon just three finalists remained, and Frei’s frequent-flyer miles jumped accordingly. Mace says the front-runner kept shifting because of each site’s unique attributes, but Western proximity and outbound supply chain considerations prevailed for two of them, “because ultimately shipments out of the country could be important for the client.”

A major factor in favor of Apex turned out to be the sheer scale of the site, Mace said. Though Nevada’s water availability is always an issue, environmental considerations also stood in the state’s favor — because of the air. “Some of the other properties we were considering were constrained from an air emissions perspective,” said Gendreau. Especially in California.

“There seems to be incredible activity and investment in the automotive industry in California, without a doubt,” said Mace, but it isn’t necessarily manufacturing. “California can be a good place to do initial startup manufacturing, but as you grow to scale in California, the constraints on cost structure, land availability and emissions are daunting. It’s a great place for talent — IP, software and design — but for manufacturing, you really have to make sacrifices for California to work.”

Growth Is One Thing, Cultivation Another

Amy Ogden and Danielle Steffen, directors of industrial/investments with the Las Vegas office of Cushman & Wakefield/Commerce, say parcel assembly for the Faraday project had a subplot all its own, involving eight parcels.

“We put that together over the course of a year, and closed April 13th, on the day of the groundbreaking, on the main parcel, after closing on other parcels throughout the year,” says Steffen. The majority of the landowners were medical marijuana cultivators, which had been directed by the state to be operational by May 2016 in order to keep their licenses.

“Because Faraday was coming in, the state said, ‘We’ll give you additional time to build your cultivation facilities,’ and worked with them,” Steffen says. A land swap was effected, with Faraday Future footing the bill for any differences in cost as well as the transactions, as marijuana growers such as Nuveda, Libra Wellness Center, Three Cups Yard, Southern Nevada Growers and Canna America Enterprises moved, some to nearby Mountain View Industrial Park. Also moved was the septic treatment facility of Honey Wagons, a portable toilet service provider.

“There were eight different parcels, with eight different owners and contracts,” says Ogden. “It was very complicated.”

No Cluster? We’ll Make One

Work on solutions to narrow the cost gap in Nevada focused first on the workforce. After all, Nevada has no automotive cluster.

Gendreau said his team’s extensive employer interviews in all candidate markets included one-on-one conversations with leaders at six Las Vegas-area manufacturers, with Faraday leadership in the room, discussing applicant flow and quality, attrition and pay rates, and skill shortages, particularly in trades, welding and certificate-level programs.

“All things considered, the Las Vegas metro in general fared well, and was surprisingly good,” Gendreau said. Moreover, the trade skills already evident will only be further bolstered by the workforce training aspect of the incentives package. “It was great to see that legislation pass,” he said. Among the standout aspects of the labor market: a steady influx of military retirees to refresh the applicant pool; low attrition rates (less than 10 percent); a loyal and diverse workforce; and affordable housing.

“That labor piece was obviously a huge concern and critical item for the company,” said Frei. “They’re a startup — hiring and training of employees will be something that will take up quite a bit of their resources and time. Nevada’s existing program was probably not designed for a large-scale manufacturer to come in, which was one reason why we let Nevada know that training would be a big site selection criterion.

“Nevada did what any business-friendly state would have done, and asked, ‘What are other states doing?’ “ Frei explained, studying the successes achieved by such programs as Georgia’s QuickStart, Louisiana’s FastStart (itself a QuickStart copycat) and Alabama’s AIDT. “Step two will be in the implementation,” Frei said. “It’s a new day for Nevada form a training perspective.”

Hard Assets, Hard Cash

Project negotiators also narrowed the cost gap on site infrastructure — water, rail and road, as well as low-cost financing for storm water drainage, internal roads, sewer and other improvements.

“Other users will benefit from them in that region,” Frei said. “Leaders saw this would be the catalyst, and were nimble and called a special session.”

The company is trying to be just as nimble. At the April 13 groundbreaking, Faraday Future’s Dag Reckhorn said, “We are moving extremely quickly for a project of this size. Our aim is to complete a program that would normally take four years and do it in half the time, while still doing it right.”

The language of the incentives legislation, like that of the special legislation for Tesla’s Gigafactory, was written so that “any supplier that locates within the site will be awarded the same benefits,” said Frei. “They just need to be added to the list of participating firms, and that’s it. That was part of the discussion from day one, and we find that to be an important consideration for an automotive company that relies on a large number of suppliers. If the suppliers are able to get benefits, they can be more competitive with pricing to Faraday. They might be separate companies, but it’s all one project.”

One project, sure. But one of several separate projects forming a hyperloop of mobility innovation out West. They are the moving parts in a bigger, regional supermegaproject that just might change the face of transport as we know it.