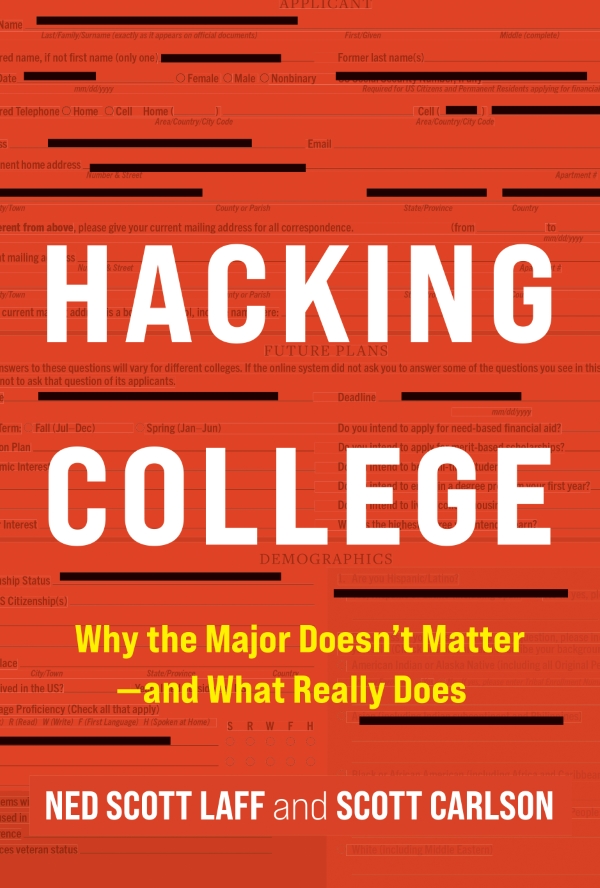

Early this year, Johns Hopkins University Press published “Hacking College: Why the Major Doesn’t Matter — and What Really Does.” Written by veteran academic affairs professional Ned Scott Laff and Chronicle of Higher Education Senior Writer Scott Carlson, the book draws on extensive research, a review of the literature and real student experiences to advocate for a proactive approach to education that encourages students to “hack” their college experience by crafting a personalized Field of Study. Here, by exclusive arrangement with the publisher and co-authors, Site Selection presents an adapted excerpt. — Ed.

The scene: The Alfândega do Porto in Porto, Portugal, along the Douro River. In September 2022, Porto hosted the Vacation Rental World Summit, where attendees included the technology companies behind websites like Airbnb and Vrbo, the trade journals covering the getaway locations, and the data crunchers selling services to optimize the property owners’ market potential.

Sarah DuPre, today the senior partnerships director for AirDNA, one of those data-crunching companies, was a keynote speaker who highlighted how data analytics of the market can reveal unexpected insights. Her presentation killed.

“When I got off stage, people asked me if I was an economist or a statistician, which is a compliment because I am definitely not either of those things,” Sarah said over Zoom about a month after her presentation, sitting on a veranda in Barcelona, where she lives. “I studied French and Spanish.”

Maybe that’s a surprise to some readers — after all, among liberal-arts disciplines getting cut at colleges across the country, foreign-language departments appear on every list. Employers, academics, parents, pundits and policymakers all have various ideas of what a liberal-arts major means to individual development and prospects on the job market. Depending on the person, that value lands somewhere between priceless and useless.

Higher education increasingly responds to market forces, but the key population driving those market forces — students and their parents — generally do not understand the nature of liberal-arts disciplines or how to apply them in the world of work. And neither do many of the people guiding those students and parents in navigating college to get a good return on investment. The Strada Institute for the Future of Work and Emsi, a labor market analytics firm now called Lightcast, called the phenomenon the “translation chasm.”

Sarah DuPre illustrates how a student from a small, unknown college with a liberal-arts major, armed with a Field of Study process, can open up unexpected career routes as she learns how to research the possibilities, fill in the blank spaces, and trade on the hard, pragmatic skills discovered in liberal-arts disciplines. For students like Sarah, what might look like luck is actually, as Seneca would say, where preparation meets opportunity.

Sarah DuPre

Senior Partnerships Director, AirDNA

Major Shift

Sarah grew up in an evangelical Southern Baptist family in Columbia, South Carolina. “You’ve seen that film ‘Jesus Camp’? That was me,” she says. “Speaking-in-tongues kind of family, super religious.” Those traditional values extended to the jobs the family would approve for

Sarah: a teacher, a nurse, or a mom. Sarah didn’t want children and couldn’t stand bodily fluids. “So, teacher it was,” she says with a shrug.

Sarah entered Columbia College, the women’s college her mom and aunt had attended, as an elementary-education major taking French and Spanish courses as electives, with the goal of becoming a French teacher. Sarah had long been obsessed with France. She attended one of the “odd” public primary schools in South Carolina that offers French, starting when she was seven years old. Later, a high-school teacher who grew up in France lent Sarah novels and storybooks from francophone authors.

After she enrolled, Sarah wanted to study abroad at Columbia’s partner universities: the University of Angers, in France, and the University of Salamanca, in Spain. The problem, she soon learned, was that the education major did not allow her to study abroad. That led her to the Center for Engaged Learning. The office’s advice was to change majors from education to French, which could still lead to viable careers after college in the hidden job market — traditionally defined as jobs that aren’t advertised and are acquired through connections, but also encompassing the many ancillary or adjacent jobs that people may not know by name but are out there to find. [In the world of global corporate location decision-making, specific jobs in corporate real estate (as opposed to commercial real estate) could be considered a hidden job market. —Ed.]

Taking that advice with a mixture of skepticism and relief, Sarah marched down to the registrar’s office on the last day of the spring semester of her freshman year to declare French as her major and Spanish as her minor. “Are you sure about this?” a staff member in the registrar’s office asked her more than once. Sarah nodded — she was certain that getting to Europe was now her goal. Then she packed up her dorm room and returned home for the summer to face the “wrath of her parents,” as she puts it.

Even Sarah initially struggled with the translation chasm, but in her sophomore year, she began to engage in a Field of Study process that would help her bridge that gap. “What do you do with a French major, anyway?” she sarcastically asked one day in the Center for Engaged Learning. To find something to do with that major, the center’s mentors prompted her to play off a problem she’d long been concerned about: the number of South Carolina middle and high schools cutting their foreign-language programs.

Starting her research investigative inquiry, she Googled keywords related to the problem and discovered the office for Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the consulate in New York City, which had a program advocating for the expansion of French courses in American schools. Late on a Friday afternoon, she put together a short email in French and sent it to the deputy counselor with a request to talk.

The following Tuesday, she received a reply asking her to stop by the cultural-services office on the Upper East Side on Thursday to discuss her email. Sarah panicked. Clearly, the deputy counselor thought she was writing from Columbia University in Morningside Heights, not a little-known liberal-arts college in the South.

She called and explained the misunderstanding to the deputy counselor’s assistant. It didn’t seem to matter to the people at the consulate, who were captivated more by Sarah’s initiative and interest in the French language than by the college she attended. The consulate set up a remote meeting over Skype.

Sarah took a day to prepare questions that addressed the social and political implications of keeping language programs alive. When she finally talked with the deputy counselor, he was impressed with her grasp of French and her concern about what middle- and high-school students would lose without exposure to foreign languages and other cultures. When Sarah asked him about opportunities for experiential learning, he offered her a summer position at the consulate.

Whole New Worlds

Aside from a trip to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, with her grandparents when she was a child, Sarah had never been outside South Carolina. New York City was a culture shock in the best of ways, as Sarah absorbed new perspectives and experiences. As Sarah’s cultural capital grew, she began to see people in important positions — those she once regarded as unapproachable — as normal human beings, and she realized she could join their ranks.

This gave her the confidence to work the room at a gala, where she met the director of a dual-degree graduate program in business and French at New York University and one of the officers in a student organization that promotes French language, culture and business within the MBA program at Columbia University. These conversations opened up her view of the hidden job market for a French major. She had so many other options than just teaching French to schoolkids.

Returning to Columbia College after a summer in New York City, Sarah planned her study-abroad experience: France in the spring and Spain the following fall. She researched the many cultural and career-relevant possibilities in Europe, approaching the experience differently from many of her peers, who tended to think of study abroad as simply about reading French literature and experiencing life in a different country. Sarah discovered she could take courses that would grant her certification from the French and Spanish education ministries to use those languages in business practices. She could also take business classes that would give her a different perspective on a facet of Western European culture not found in simply studying literature.

Sarah aced those courses and came back certified to use French and Spanish in myriad commercial settings, from business negotiations to broadcasting for the media. But when she returned to Columbia College, Sarah was in for a shock: Her faculty advisor, the chair of the French department, would not accept her credits in business language or the French business courses as electives for the major. The department would only accept studies in French literature. Courses in business language and practices — taught in French and concerning current issues in France’s economy and everyday economic life — didn’t qualify as French culture and would not count toward her major requirements, Sarah was told.

Sarah ran headlong into a faction of higher education that views the study of liberal arts in college as mostly a personal exploration of the canon of humanistic knowledge, a faction that takes a skeptical view of college as career preparation. The liberal arts are not about arming students with the skill sets catered to a specific job, they say; in fact, these liberal-arts advocates often refer to those disciplines as “nonvocational.”

Sarah was enraged. To meet the department’s requirements, she would have to spend another year at the college. But she thought about her experience in New York City, where she had met people from the French studies department at New York University; she researched that program, which combined skills in French and business, and realized she could use it as a model to design her own major. She put together her work in France with her studies in Spain, added courses in marketing and statistics to flesh out her degree plan, and dropped her French major.

She needed an internship—and a lightbulb switched on when one of the peer mentors in the Center for Engaged Learning asked her, “Who sells South Carolina?” As it turned out, the South Carolina International Trade Association was heavily involved in luring businesses from France (and many other countries) to operate in the state and utilize the Port of Charleston for imports and exports to the world.

Sarah set up a research investigative inquiry with the CEO of the trade association, who quickly hired her because of her language certifications and experience to conduct market research. “I was the only person with a bachelor’s degree in the office,” Sarah says. “I learned that others on the team were from the Masters of International Business program at the University of South Carolina — everybody was from a different country, from Italy, Germany, Austria and China.”

Eventually, Sarah felt a yearning to get back to Europe, particularly Barcelona, where she had fallen in love with the city (and someone she’d left behind there). She set her sights on enrolling at ESADE, an internationally ranked business school in Barcelona, and started another series of research interviews to find a scholarship. She came across one offered by Rotary International and talked to a local representative of Rotary, who gave her a tip for winning an award: At the welcome party, he said, “work the room,” because the scholarships always went to people who impressed Rotary’s board members.

“I had identified the seven people on the board I needed to mingle with, looked them up on LinkedIn, and came up with something interesting to say to each of them,” she says. “Something that’s a bit outside the box.”

Having created a narrative about her journey through Field of Study, Sarah had everything she needed to tell her story to the board members — how she consciously linked French and Spanish to business and contemporary culture. After the event, Sarah was one of the awardees.

‘Open It Yourself’

She went off to ESADE, picked up Catalan and did an internship with a start-up company that sharpened her skills in business intelligence and market research. She graduated and used her skills to land a position with a Barcelona-based start-up called AirDNA in 2016. That same year, the French department at Columbia College closed, along with other departments with withering enrollments, including philosophy and history. (Spanish was reduced to a minor.)

The French department could have found myriad ways to boost its enrollment numbers, given that South Carolina is now host to more than 1,200 international companies employing more than 170,000 people. The French faculty could have worked with the career-services office to make connections with those companies and create partnerships with local high schools offering French, thereby showing students the inherent marketability of the language and setting up a pipeline into the college’s French program.

French, after all, is consistently listed as one of the most useful business languages in the world, applicable not only in France but also in parts of Africa, Canada, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia. By showing how French could interact with the blank spaces present in almost any degree — without changing anything the French faculty were already doing in their courses — the department could have brought together the vocational and nonvocational to bridge the translation chasm and perhaps have fended off its demise.

Part of Sarah’s success comes from her tenacity and her refusal to take no for an answer. Another part comes from how she consciously arranged her interests, passions, skills and her degree into a pattern that she and others could understand.

“There really is a hidden job market for people who know how to just show up and say, ‘Hey, I have this skill set, and this is how I can be beneficial to you,’ ” she says. “If you’re good enough, they’ll make space for you. Don’t wait for somebody else to open an opportunity. Just go and open it yourself with what you want to go after and what your skill set is. And I do that every day. My job is made up.”

Scott Carlson

Ned Scott Laff, PhD

Blank Spaces and Wicked Problems: A Field of Study Glossary

In “Hacking College,” Ned Laff and Scott Carlson introduce a number of terms used to buttress their argument for a “field of study” approach to college.

Field of study: It’s not a major, but an individually designed method that offers “a wider lens on the college experience” unifying disparate pieces of programs, connecting interests to studies and allowing students to take ownership of their education instead of checking off degree requirement boxes. The path forward, Laff wrote in his first note to Carlson, “lies in the intersection between students’ ‘hidden intellectualism’ and the ‘hidden job market,’ which career services are not set up to explore.”

Hidden intellectualism: University of Illinois at Chicago Professor Gerald Graff coined the term to refer to the motivating interests students bring to college from their everyday lives — “baseball, motorcycles, Bible Belt religion” — that are legitimate areas of study and through which students can connect their latent or hidden intellectualism to the intellectual resources on a campus.

Hidden job market: Traditionally defined as jobs that aren’t advertised and are acquired through connections, this term is expanded by the authors to include “the granularity of positions that exist in any world of work,” i.e., the many “ancillary or adjacent jobs that people may not know by name but are out there to find.” In Site Selection’s world of global corporate location decision-making, for example, specific jobs in corporate real estate (as opposed to commercial real estate) could be considered a hidden job market.

Vocational purpose: Binding one’s interests, skills and talents with a personal sense of purpose in the vast world of work.

Wicked problem: A fuzzy, complicated, pressing and perhaps unsolvable human predicament requiring a multidisciplinary approach. In essence, say the authors, a student’s college career represents a personal wicked problem.

Blank spaces: The “electives and other open choices that compose most of the undergraduate degree — spaces that students have to figure out how to fill, a crucial but underappreciated aspect of college.”

Social capital: How students can expand their professional and social networks while pursuing an undergraduate degree.

Cultural capital: The competencies, knowledge and skills a person acquires from the environment in which they live. “Cultural capital is the primordial goo that hidden intellectualism emerges from,” write Laff and Carlson.

Research investigative query: What the authors label as “the engine of the Field of Study process,” the research investigative query is a learning agenda strikingly similar to journalism, with four components: 1) Research who is doing what they want to do or something similar. 2) Set up personal interviews. 3) Bring substantial questions and genuine curiosity to the interview. 4) Identify faculty and staff on campus who have interests similar to the experts being interviewed in the hidden job market.