New work published in the journal Joule by an MIT team started as research about membranes for water desalination, but is really about eliminating the filters between academic research and real-world applications.

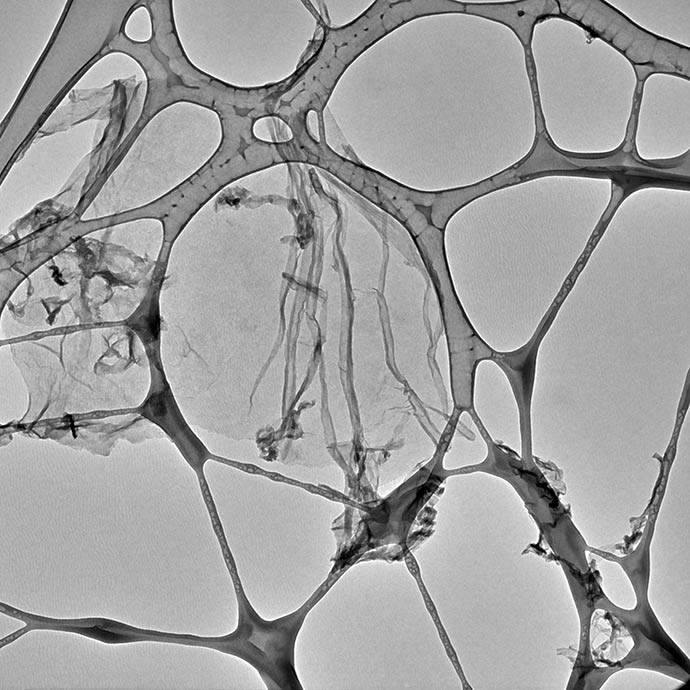

As an MIT release in early October explained, Shreya Dave, a former MIT doctoral student, was working with Jeffrey Grossman, a professor of materials science and engineering at MIT and today the Morton and Claire Goulder and Family Professor in Environmental Systems, on a new type of filter made from graphene oxide that they thought could improve flow rate by hundredfold over conventional polymer filters at desalination plants.

But one of the conditions of their National Science Foundation I-Corps grant for the project was to interview 100 professionals across the desalination industry. The team doubled down and talked to 200 instead. Those unfiltered conversations allowed nuts-and-bolts reality to permeate the research. The findings:

- Estimated costs for the new membrane material (which cost around $15 per sq. meter) would represent at least a 50-percent increase over that of existing membranes, when the total costs of plant operation were taken into account.

- Using the new material would lead to only an estimated 15 percent improvement in output.

In other words, what looked good on paper wasn’t good enough to justify introduction of the new membrane as it was. But the cumulative result of those industry conversations turned the MIT team in a new direction: the chemicals arena, including pharmaceuticals.

It turns out that chemical separation processes such as distillation and evaporation account for 12 percent of the total energy use in the United States. "But using a filter instead of the traditional processes, the team found, could eliminate 90 percent of that energy use," says MIT. According to the authors in their paper, that translates to saving 11 quadrillion BTU, or $200 billion annually.

The work also could apply to the food and beverage and pharmaceutical sectors. In the latter, "although manufacturing represents a small fraction of the total cost of a drug, throughput-constrained facilities would benefit from solvent-stable membranes that can be sterilized," they write. "Efforts toward continuous manufacturing of pharmaceuticals require qualified membranes, and new drug development could be enabled with improved separation capacity." Other graphene research at MIT has focused on applicability in drug delivery to targeted areas in the body, and in sensing disease agents in the bloodstream.

Ironically, even though this particular membrane research has taken a new path away from desalination and toward process industries, but research shows how important desal work will be to those very industries in years to come. "Industrial Desalination & Water Reuse: Ultrapure waer, challenging waste streams and improved efficiency," a report released in April 2017 by Global Water Intelligence (GWI), predicts that salt removal and wastewater recycling technologies are "expected to become an essential ingredient in operational strategy, growing by 11.4 percent over the next five years" to reach a total market value of more than $11.9 billion by 2025 — including oil & gas sector activity rising by 14.2 percent this year, and pharmaceutical sector activity rising by 6.2 percent.

Revving the Engine

Meanwhile, the work done by Dave, Grossman and co-researchers Brent Keller PhD ’16 and Karen Golmer, innovator in residence at MIT’s Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation, has resulted in more than a published paper. It’s the basis for the new company Via Separations, where Dave is CEO, Grossman is the chief scientific officer, Keller is the company’s CTO, and Golmer its head of business development. The company in September was one of seven (including several life sciences/health startups) that won funding from MIT’s The Engine, founded to help bring transformative "tough" technologies along the arduous path from the lab to the marketplace. All based in Greater Boston, the seven firms include ytopen, which is working on accelerating the development of genetically engineered cells by developing technology that modifies microorganisms 10,000 times faster than current state-of-the-art methods; and Suono Bio, which aims to enable ultrasonic targeted delivery of therapeutics and macromolecules across tissues without the need for reformulation or encapsulation.

As MIT explains, keeping the big picture in mind — i.e. looking up from a specific issue at the lab bench to what it means in day-to-day industry — is essential. “In industry, they don’t care about individual components," says Dave. "They’re looking at whole systems."

"Getting out into the trenches, you really do find out where their challenges are,” Grossman says. “You learn a lot from that experience that’s not out there in the literature. You can’t find this stuff in papers.”

And yet, they observe, research papers on using graphene in desalination have continued to grow by leaps and bounds, even as the costs associated with such an application continue to be well beyond reasonable. The researchers put it bluntly in a graphic where large ovals depict where industry could most use the technology, vs. a small yellow dot where the research is concentrated. "There is a mismatch between what is available and what is desired, and yet the bulk of academic research is focused on the yellow dot," they write.

According to the team, the cumulative time spent interviewing desalination professionals was seven weeks — approximately 2 percent of the seven years the team has spent on the research. In other words, it’s not an inordinate burden to talk to people, especially when those industry insights can turn a project in a better direction. And other MIT research continues studying other challenges in the $13-billion desalination industry, such as a study out this week about the search for what causes membrane fouling in reverse-osmosis facilities.

In addition to the National Science Foundation, the graphene project was supported by the Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation, the Abdul Latif Jameel World Water and Food Security Lab (J-WAFS) at MIT, and The Engine, says the MIT news office. "The company, Via Separations, has won an SBIR Phase I grant and aims to have prototype separation systems in place for real-world testing within a year."