As a national leader in wind and solar energy with ambitious goals to decarbonize, California has nonetheless lagged other coastal states in developing offshore wind power. The reason for that is simple. The continental shelf off California’s coast plunges steeply and deeply, far more so than do the coastal waters off the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, where massive wind turbines can be bolted to the sea floor.

For California, the more recent development of “floating” wind turbines that are tethered to the floor by cables is a hoped-for game changer. So much so that last August, the state government set a target of adding 25 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2045, enough to power an estimated 25 million homes.

Getting there will be a tall order, one that’s likely to require hundreds of billions of dollars of public and private investment and the offshore deployment of some 1,700 15-megawatt wind turbines. And that’s just for starters.

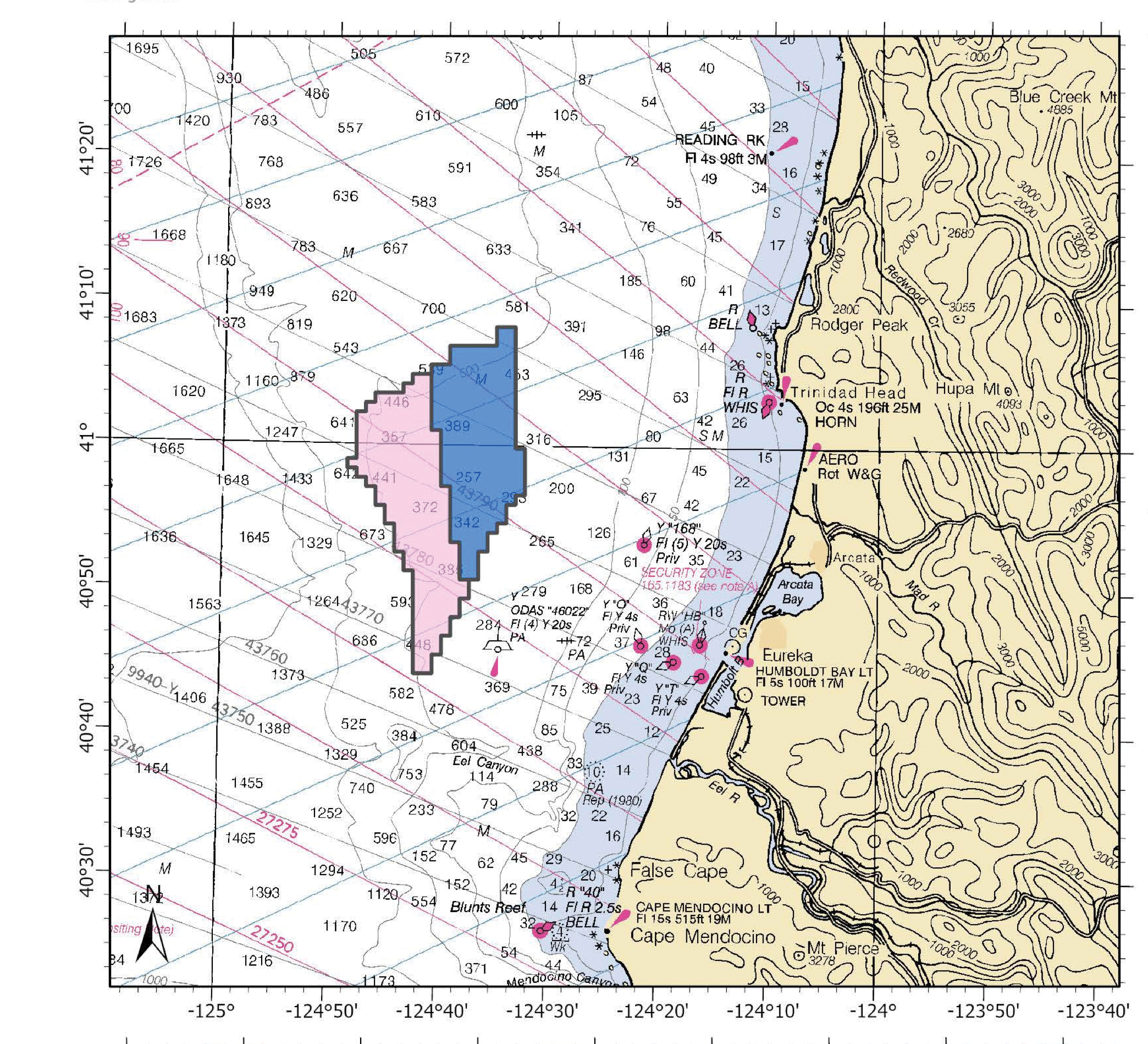

Image courtesy of BOEM

“I think of offshore wind as being about five distinct projects,” says Arne Jacobsen, director of the Schatz Energy Research Center at Cal Poly Humboldt in Arcata, formerly Humboldt State University. “Building the wind farms is one endeavor. Building out the ports to support them is another. Building transmission lines is a third, and then there’s building the workforce and the supply chain.” All from scratch.

Yet the opportunities are vast, and the wheels are turning and gaining momentum. Years of feasibility studies culminated last December in the initial auction of Pacific region wind area leases by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). Five companies bidding a total of $757 million were awarded leases covering 373,268 acres within two federally designated wind areas off central (Morro Bay) and northern (Humboldt County) California. The leased areas have the potential to produce over 4.6 gigawatts of offshore wind energy, about one-fifth of California’s eventual goal.

“This auction,” said BOEM director Amanda Lefton, “commits substantial investment to support economic growth from floating offshore wind energy development — including the jobs that come with it.”

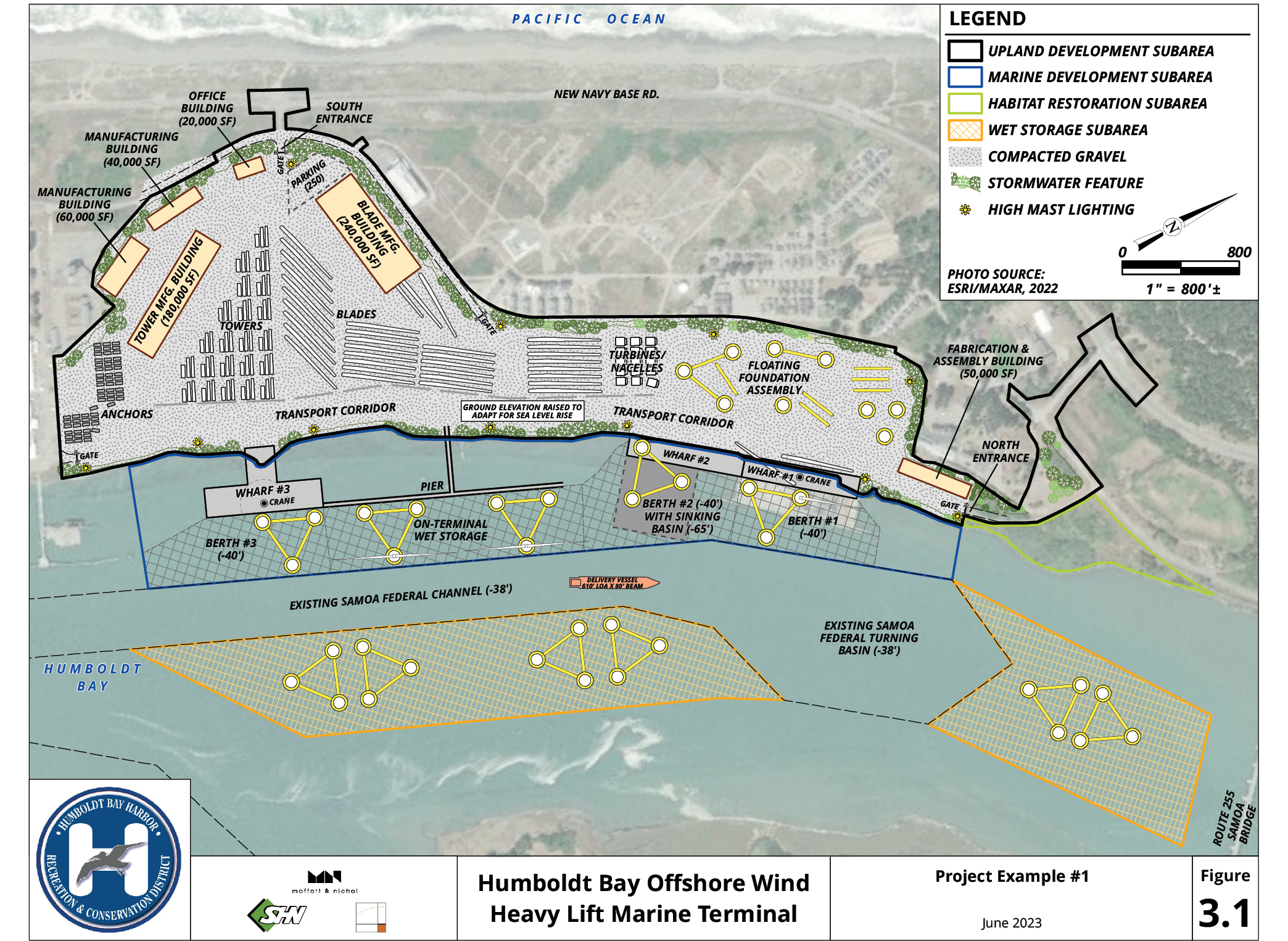

Rendering courtesy of Humboldt Bay Harbor District

A New Vision for Humboldt Bay

Two of the wind lease areas — purchased for a combined $330 million by Vineyard Offshore and Germany’s RWE — lie adjacent to each other about 20 miles off Humboldt County, some 270 miles north of San Francisco. For the deepwater Port of Humboldt Bay, whose waning fortunes have paralleled the decline of northern California’s timber industry, the development of offshore wind offers an opportunity to reinvent itself and to bolster the fortunes of the community that surrounds it. The port has received a $10.5 million grant from the California Energy Commission (CEC) to initiate renovations that will eventually support the onshore assembly of turbines and other components and their transport to sea.

“It seems inevitable that we will be the first wind port on the West Coast. Humboldt will be a leader in energy, decarbonization and addressing climate change.”

— Rob Holmlund, Development Director, Humboldt Bay Harbor District

“The project,” said CEC in a release, “is expected to revitalize the waterfront industry in Humboldt County and provide living wage jobs to nearby communities.” An economic assessment found that an envisioned 170-acre terminal to support the offshore wind industry could generate as many as 830 local jobs and more than $130 million in industry output over a five-year period.

“It seems inevitable that we will be the first wind port on the West Coast,” says Rob Holmlund, who is overseeing the project as development director for the Humboldt Bay Harbor District. “Humboldt,” he tells Site Selection, “will be a leader in energy, decarbonization and addressing climate change.”

As if to solidify the port project’s viability, the Harbor District has reached an agreement with Crowley, one of the global leaders in maritime and energy solutions, to exclusively negotiate to build and operate what’s to become known as the Humboldt Bay Offshore Wind heavy Lift Marine Terminal. In April, Crowley cut the ribbon on its inaugural office in Eureka.

“We are excited about the opportunities Crowley brings to the table — living-wage jobs, opportunities for local businesses to engage with them, and economic development for our community overall,” said Nancy Olson, president and CEO of the Greater Eureka Chamber of Commerce.

Costs vs. Opportunity

Estimates of what it will cost to redevelop the Humboldt port, including the new terminal, are all over the map, but Holmlund believes it could exceed $1 billion. Much of that will depend on which parts of the massive turbine components end up being manufactured at or near the port and which are imported for final assembly from elsewhere.

“We are likely going to see that the major components are going to be manufactured in European markets and Asian markets overseas and brought here by ship,” says Scott Adair, director of economic development for the City of Humboldt. “And then really what’s occurring here is the assembly of these pieces. But the hope is that we can start developing the capacity so that maybe for the second or third phase, we aren’t having to bring those components in from overseas but that we are able to manufacture those components here in the U.S.”

As Holmlund points out, there is much to be produced beyond the mammoth turbines and stands that support them. Here’s some back-of-the-envelope math regarding just the the cables required to tether floating wind platforms to the seabed.

“Each one of these [1,700] platforms requires three mooring lines. So, you need 5,000 total lines to be manufactured, each one being about 3,000 feet long. So,” he figures, “that’s 15 million feet, or about 2,800 miles of mooring lines. It is a massive undertaking to manufacture these, and there’s nothing like this currently being manufactured on the West Coast. It’s a whole new manufacturing industry. And that’s just the mooring lines. They’ll need miles and miles of transmission cables. I haven’t been able to calculate that one yet.”

Photo courtesy of NREL

The point, he believes, is “there is a suite of new industries that all need to be created on the West Coast that currently do not exist. If we want to capture that manufacturing opportunity, we’ll need to invest even more.” And if it costs a billion dollars, well, that’s California relative.

“A billion dollars does sound like a lot, and of course it is,” he says. “But if you look at what California spends on freeways every year, it’s nothing.”

He’s run the numbers on that, as well.

“A four-lane freeway in California turns into a billion dollars after six miles. And there’s no private investment in that. We anticipate there will be private investment in our project. If we can get public funding for two-thirds of the total project costs,” he says, “that would go into public lands and be public infrastructure in perpetuity. And it’s all to manufacture energy systems for the state to reach its goals.”

Holmlund cites an estimate by the California Association of Port Authorities of $10 billion to develop port infrastructure at other support hubs, such as the Port of Long Beach, near the Morro Bay area. Smaller supply chain components could even come through ports like those of San Diego and San Francisco, just not the huge components that could never get past the Golden Gate Bridge and other such structures that commonly limit access to seaports.

Can California Still Do Big?

It is worth bearing in mind that, more than a quarter century since the foundation of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, California still doesn’t have high-speed rail. In an extraordinary lament to his state’s inability to see major projects through, Gov. Gavin Newsom, in June, fairly roared through the pages of the New York Times.

“People are losing trust and confidence in our ability to build big things. People look at me all the time and ask, ‘What the hell happened to the California of the ’50s and ’60s?’ We need to build,” he wrote. “You can’t be serious about climate and the environment without reforming, permitting and procurement in this state.”

Gov. Newsom directed his ire at his state’s powerful army of environmentalists, some of whom have banded together to take him to court over some of the physical underpinnings that support California’s ongoing conversion from fossil fuels to electricity.

“The governor,” says Adair, “is signaling that he will not allow or tolerate minor environmental disruption to impede these projects. He believes that the overall positive effect for the climate is greater than those smaller considerations.”

With Newsom’s support, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO), in late May, endorsed investments totaling $7.3 billion in new and expanded transmission capacity — including towers, wires, transformers and substations — that will help interconnect new clean power generation. He has vowed to streamline permitting processes to move projects along more swiftly.

The Schatz Center’s Jacobsen, who has spearheaded numerous studies on the feasibility and now the implementation of California’s wind project, believes public support for the project could hinge upon the finer details of how it’s designed. Humboldt County, he says, already is under stress from rising housing prices and a lack of access to healthcare, problems an influx of workers would only serve to exacerbate.

“If the workforce is going to consist primarily of people outside of the region, that’s a really different look than if workforce development is done in a way that jobs will be locally generated, and people see that there’s a pathway for them to be involved.”

“The governor is signaling that he will not allow or tolerate minor environmental disruption to impede these projects. He believes that the overall positive effect for the climate is greater than those smaller considerations.”

— Scott Adair, Director of Economic Development, City of Humboldt

More broadly, he believes, “NIMBY” concerns tend to wither when benefits accrue to the broadest range of Californians.

“The question is whether there‘s a large enough constituency to carry it forward. How will it be designed from a jobs and economic development perspective? From an electricity reliability perspective? From an environmental perspective? People support it when they see that it will deliver significant benefits to them.”

Says Holmlund: “There are people that oppose every project, everywhere, all the time. There’s a process for that, and I don’t see it as a critical challenge, not like the funding, the workforce, logistics and the transmission piece.

“The bottom line is that we need to decarbonize our energy system. We can sit around and wait for others to do it, or we can participate in something that’s really desperately needed.”

California is Tops for Foreign Investment

For the second straight year, California leads the nation in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). In a release issued July 10, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that California totaled $29 billion in FDI in 2022, followed by Texas ($20.7 billion) and Illinois ($10.9 billion).

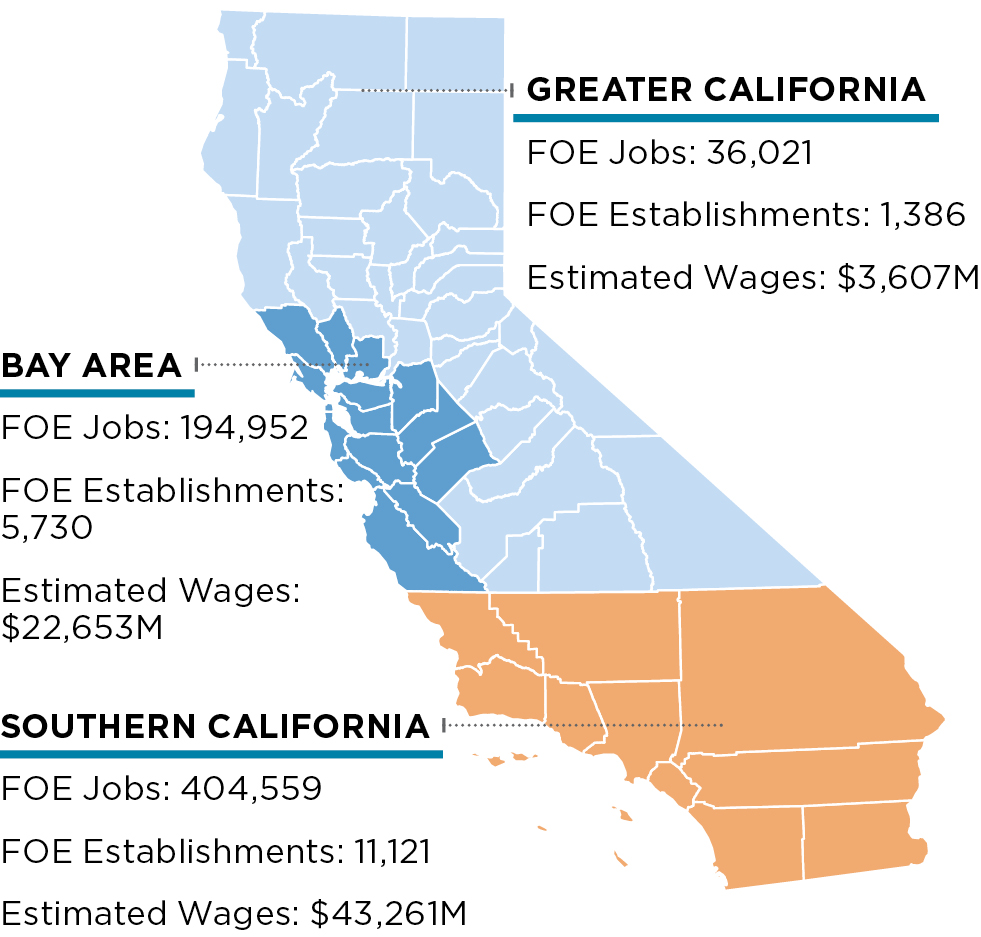

A separate analysis published in April broke down the distribution of foreign investment among regions designated as Southern California, the Bay Area and Greater California, with the 10-county region of Southern California shown far and away to be the leader. The report by World Trade Center Los Angeles in partnership with Loyola Marymount University identified more than 11,000 foreign-owned enterprises (FOEs) employing more than 400,000 workers operating in Southern California.

“Southern California,” says the report, “is preferred by FDI targeting industries such as wholesale trade, retail trade, transportation, hospitality, and administrative services. In addition, FDI in manufacturing, finance, and real estate industries manifests significant growth trends. These trends indicate that foreign investment for those industries has gradually concentrated in Southern California.”

In all, the report estimated that 18,237 FOEs were operating in California in 2022, employing 635,532 residents and paying an estimated $69.5 billion in wages.

“This year’s report,” the authors said, “shows the beginning of a rebound from the detrimental effects of the pandemic, as California gained 271 foreign-owned enterprises and over 5,300 workers employed by FOEs.”