The first rule is that there are no rules.

Physicist Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of Manhattan Project director J. Robert Oppenheimer, didn’t say those exact words when he founded the first-of-its-kind hands-on museum the Exploratorium in the late 1960s. But you know he wanted to.

“I remember one meeting where someone was trying to convince Frank to agree to a practical solution by saying ‘But Frank, we live in the real world,’ ” recalls one colleague in a museum article. ” ‘No we don’t,’ Frank said. ‘We live in a world we made up.’ “

Oppenheimer, who died in 1985 of cancer, knew all about improvisation. His research career at the University of Minnesota derailed due to harassment by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1949, New York City native Oppenheimer became a cattle rancher in Colorado. While teaching at the local high school, he often took students to the dump and used abandoned auto parts to teach principles of mechanics, heat, and electricity. At a subsequent post at the University of Colorado, he created a “library of experiments” that was a prototype of sorts for the Exploratorium.

Making the world up as we go along could easily be the mantra of the Bay Area’s hackerspace and maker community, that loosely defined group of people engaged in small-scale, hands-on invention, fabrication and exploration in garages, workshops, makeshift R&D labs and boutique manufacturing sites around the country. Certain places such as Brooklyn, N.Y. (home to Maker’s Row, among other organizations) have seemed to develop clusters of makers, and the Bay Area is one of them: The annual Maker Faire founded by Make magazine in 2006 and held in San Mateo draws 120,000 people.

The Exploratorium (a Maker Faire partner) draws more than 550,000 people a year, and reaches millions more through its programs and traveling exhibitions, on display at more than 1,000 science centers, museums and public spaces around the world. The museum even inspired some “hands-on tinkering” by both men and women at a science festival in Saudi Arabia.

Every middle and high school in the Bay Area has been touched by the Exploratorium Teacher Institute. Ninety percent of beginning science teachers who graduate the Exploratorium’s two-year mentoring program are still teaching science today, compared to a 50-percent national attrition rate, says the museum.

Since its founding, the institution has been located at the Palace of the Fine Arts. But its leaders decided to make up a new world, and as of mid-April, after several years and the work of 81 different partners, the museum’s new home is a $220-million, 330,000-sq.-ft. campus on Pier 15 along the Embarcadero on San Francisco’s historic waterfront.

In a release, one of those 81 project partners, San Francisco-based general contractor and construction manager CB2 Builders, describes the scope and challenge of the work, which was completed on time and on budget:

“With its high-profile location, landmark status, numerous public and private stakeholders and 600 intricate art and science exhibits, the Exploratorium was an extremely challenging project and, likely, the most unusual of the many construction projects under way on the rapidly evolving Embarcadero,” said CB2 Project Manager Tony Campagna. “In taking on this very dynamic assignment, we understood that we needed to be flexible and adjust our priorities on a daily basis — otherwise procedures would get in the way of progress.”

“Crucially, the CB2 team understood the Exploratorium as a client-a creative entity with a non-linear way of thinking,” said Exploratorium Project Director Kristina Hooper Woolsey. “They were masterful in their role, and like the museum itself, CB2’s approach was a mix of art and science — creative and flexible, yet disciplined and detail oriented.”

Among the challenges and accomplishments:

- CB2 was responsible for coordinating approximately 24 entities including the Exploratorium and its work groups, i.e. exhibits, outdoor exhibits, shop, and bio-lab and many others; Port of San Francisco (permits and inspections); outside vendors associated with exhibits and other scopes of work, i.e. AV, telecom; structural engineer; and base building contractor, to name a few.

- Due to the unusual nature of the base building construction (a pier over water), work below-slab involved executing from a boat. With slab penetrations limited to two inches in depth, CB2 collaborated with the structural engineer to develop anchoring solutions to accommodate structures, equipment and exhibits within tight constraints.

- Constructing the “distorted room,” an entirely new, 30,000-pound structure built to the Exploratorium’s specifications. Designed to challenge the notion of perception, the room is neither square nor plumb and also has to be entirely mobile as it is used at corporate events and other gatherings.

“The port’s unique location is a powerful tool to balance the difficult and lengthy development process,” says Phil Williamson, project manager for the Port of San Francisco. Asked what helped expedite the museum project, he says, “I am not sure if ‘expedited’ fits the path the Exploratorium project followed. Site selection due diligence, site entitlements and document negotiations took quite some time. Once construction began, as challenging as it was, the bulk of the overall schedule and project risk was behind us.”

“An atypical client, fluid scope of work, stringent code requirements and tight schedule made this a particularly demanding assignment, but also an exceptionally rewarding one,” said Campagna. “We had the pleasure of working with an outstanding group of intelligent, creative people that challenged us, and resulted in the creation of an extraordinary museum and campus.”

“Waterfront development in San Francisco is a complicated process,” says Williamson. “The port’s recent experience successfully entitling major projects is proof positive that its staff, regulatory partners and end users can work together to add value, preserve and enhance maritime opportunities, create jobs and add new public open space at the Port of San Francisco.”

Are there also ways in which an institution with the international stature and connections of the Exploratorium contributes to the area’s economic development in indirect ways?

“In short, yes,” says Williamson. “As a 16-year employee of the Port and lifelong Bay Area resident, I noticed a palpable change in the activity level in the vicinity of the Exploratorium once it opened. The creative vibe that defines the Exploratorium directly transferred to the adjacent street scene as their employees and curious patrons activate and enliven the already bustling Embarcadero. That said, the Exploratorium has only been open at their new home three months, and the depth of follow-on effect and impact to the neighborhood it will have remains to be seen.”

Tools for Creating

The Exploratorium recently partnered with a number of leading California corporations to expand or develop programs that strengthen scientific literacy by enabling more than 20,000 Title I school students to visit the institution. One of those companies — Autodesk — is an invention enabler in its own right. And it’s growing on the waterfront too, locating its consumer products team to Pier 9. That makes for an easy walk to the new Tinkering Social Club it’s helping to sponsor at the museum, designed to bring together maker movement enthusiasts.

Last September the San Francisco Port Commission approved a five-year lease and $3-million improvement program for Autodesk to renovate and occupy 8,391 sq. ft. on the pier. In January this year, the lease was expanded to 27,190 sq. ft. for 10 years with a minimum of $7 million in planned improvements, according to published reports.

The move was driven in large part by fast-accumulating demand for 3D modeling and printing. The new space will host robotics, nanotechnology and synthetic biology equipment. The firm is also moving into 108,000 sq. ft. at One Market in the city by mid-2014. The company, known for its design and modeling software such as AutoCAD, has tripled its San Francisco work force in the past five years. The San Rafael-based company had FY 2013 revenues of $2.31 billion, and employs 7,300 worldwide.

Noah Cole, senior manager, corporate public relations, says Autodesk was founded just across the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County, and for most of its history has grown there. But acquisitions have led to increased space in San Francisco, where he says the company has steadily increased its presence for two primary reasons: “It’s easier for us to hire in San Francisco, and getting customers into San Francisco is a lot easier. We still maintain a lot of people at corporate headquarters in Marin, and have a back office there. But for certain type of things, especially as we develop more cloud software, or for the maker community, San Francisco is really a hotbed and makes much more sense for us.”

The space at One Market is home to between 500 and 600 employees, as well as a LEED-Platinum-certified design gallery. About two years ago, the company acquired Instructables, an online community for people who make things, whether it’s “cake, a costume or a marshmallow gun,” says Cole. “The Instructables team actually tests out some of the stuff they do, and they’ve been working out of a fairly small facility crammed into one office. So we’ve been looking to find a space to expand them and other teams. That led us to expanding at Pier 9.”

Start-Up Space

Helping select that spot was what Cole calls “a fairly robust corporate real estate team. The requirement was to find some light industrial space within walking distance of our main site at One Market. Ultimately it’s some office space, but also a workshop space, with 30,000-pound water-jet cutters, and massive five-axis routers. Doing that in industrial space didn’t make sense. We wanted to get that equipment in and out and get the things created there in and out. We found out there was an opening from a company vacating their space.”

That company was DNA Direct, now relocated to South Carolina after being purchased by a larger firm. According to meeting minutes from the port, Autodesk will receive a rent credit of about $2.9 million, while the port will see about $55,000 a month in rent. Cole says the company has received great support for its growth from San Francisco Mayor Edwin Lee and the city’s Board of Supervisors, as well as the port.

Dennis Conaghan is the executive director of the San Francisco Center for Economic Development (SFCED) and the former COO of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, with 30 years of commercial real estate industry experience prior to taking on the Chamber role in 1999. He says the creative spark can apply to policies too, referencing the Upper Market Street area of the city.

“There is a tax incentive program there for people interested in relocating to the area that involves a relaxation of the payroll tax,” he says. “It also has a provision for corporate profits and how they are taxed. It’s why Twitter, Zynga, Dolby and other firms have relocated to the area. It’s very enticing for them.”

Cole says the Autodesk space is a mix of offices, meeting and workspace, including a bio-nanotech wet lab that is experimenting with Autodesk design technology to do programming and design at the molecular level. He says the company may be 30 years old now, but “it feels like we’re a start-up, because there are a lot of startup businesses inside [the company]. This space feels like a start-up. We want to have that type of atmosphere.”

Autodesk thrives in what Cole calls the “really vibrant maker community” in San Francisco. Among its investments is a company called TechShop, which provides a library with 3D printers, workstations, wood shops, paint shops and metalworking facilities to start-ups looking to create prototypes. The firm has facilities in Detroit and in other cities as well. “We do see this growing maker movement,” says Cole, “and we’re trying to tap into that with our software and our facilities.”

Joan Price, a principal at Gensler in its San Francisco office who was a co-author of the award-winning “Spaces for Growth” report issued by Gensler and SFCED, says, “There’s definitely an emergence of a desire to return to the urban core, specifically in the tech sector. There’s a desire to locate very near other like-minded, innovative companies. And allowing choice for employees is a big deal.”

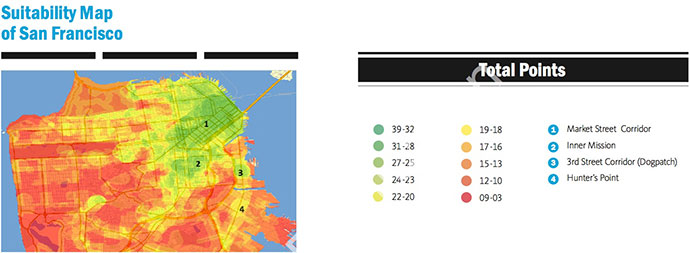

She says the team that compiled the report, which used GIS to evaluate city hot spots for tech firm growth, referred to some of these concepts as it surveyed leaders of young companies. She uses terms such as “hackable space,” “authentic” and “garage.”

“It’s reminiscent of where these companies started,” she says. “A lot of companies are looking to create environments like a start-up. In the maker movement, you might even be building your own furniture for your office space. They’re calling it ‘hackable spaces.’ The office environment is not all that precious. What’s precious is the talent that resides in that space.”

SFCED’s Conaghan also has been observing the corporate move toward urban environments, not only accessing the talent but the quality-of-life and cultural amenities that talent craves. In the process, sometimes those companies turn into cultural treasures all their own.

“Autodesk’s location in San Francisco is a literal think tank,” he says of the One Market Street location. “It’s a museum of ideas and innovation.”

Autodesk’s overall expansion in the city is adding several hundred jobs to the company’s payroll over several years, says Cole, while also consolidating from several facilities in the Bay Area and Toronto. “We had 300 eight and a half years ago in San Francisco, and will have more than twice that this year,” he says. With the Pier 9 expansion we’ll grow to about 287,000 square feet [26,662 sq. m.] in San Francisco and will have capacity for about 1,000 employees. Our future growth is planned to be primarily in San Francisco.”

And that growth will come from consumer products, which are essentially the bridge between the company’s 12 million professional customers and the approximately 100 million people now using Autodesk’s first consumer product, SketchBook, on mobile devices.

“Our CEO Carl Bass is a woodworker himself, with a shop in Berkeley,” says Cole. “He’s been actively involved in spec-ing the equipment for this new office. He had final say on what went in, which system in the ducts, which router and water jet, and the whole range of 3D printers.

“What we’ve figured out,” he continues, “is there is a large group of people out there who want to create things, and if we can get the technology into their hands, amazing things can happen.”

Frank Oppenheimer, one imagines, would approve.