“We’re healthy enough. We’re beautiful enough. We’re smart enough. And doggone it, people like us.”

It’s hard not to channel affirmation-sputtering character Stuart Smalley every time a ranking is released by the Geneva-based World Economic Forum. That’s because so many of those indices seem to rank the WEF’s home country of Switzerland near the top.

You can’t blame them. What’s not to like about a nation that is the year-round home of some of the globe’s most gorgeous mountains and elite companies, and which plays host to the world’s elite individuals every January in Davos. The country’s legendary neutrality always places it above the fray. Two Swiss guys — the powerful and cool Stan Wawrinka and the picture-perfect Roger Federer — comprise the remaining three tennis players (as of this hour) in this week’s Australian Open. Everything about the Swiss simply exudes panache, tinged with a soupçon of sophistication, infused with un certain je ne sais quoi that just sounds like they’re better … especially when expressed with their superior multilingual capability.

Then again, the annual event that kicked off this week in Davos is really just like any other conference: Attendees circulate among the keynotes, reports and proclamations, gradually approaching a crescendo of self-congratulation and self-importance that outdoes any affirmation, as they lend the convocation sufficient gravitas to justify everyone’s expenses.

Capital investment is the name of the game, after all. But one of the latest WEF reports, originally released in October, provides a possible tool for capital investors by calibrating human capital’s influence on spending decisions.

The World Economic Forum’s Human Capital Index (HCI) defines a nation’s human capital endowment as “the skills and capacities that reside in people and that are put to productive use” and says such a measuring stick can be a more important determinant of a country’s long-term economic success “than virtually any other resource.”

The HCI evaluates 122 countries according to 51 indicators across four pillars: health and wellness; education; work force and employment; and the “enabling environment,” i.e. the “legal framework, infrastructure and other factors that enable returns on human capital.”

Yes, Switzerland tops the rankings, “demonstrating consistently high scores across all four pillars, with top spots on Health and Wellness and Workforce and Employment, second place on Enabling Environment and fourth on Education.” Eight of the Top 10 countries are from Europe, encompassing another perennial rankings maven, the Nordics, with Finland at No. 2, Sweden No. 5, Norway No. 7 and Denmark No. 9. The Netherlands lands at fourth, while Germany comes in at No. 6 and the UK finishes eighth.

The only territory to break up the Euro party was Singapore (No. 3), the famously proficient Asia Pacific city-state that some might be willing to lend honorary Nordic status if its even keel weren’t more equatorial than glaciated in nature. Canada rounds out the Top 10, mostly by virtue of its second-place finish in the education criteria.

Familiar Trends

The HCI’s authors are the first to admit that “there is a strong correlation between national income and human capital across the 122 countries,” but they note “there are also variations within each income category and unique experiences that can serve as examples within income groups. Among the lowest-income countries — those with around US$1,000 per capita GNI [gross national income] — countries like Kenya and the Kyrgyz Republic perform far ahead of countries such as Malawi or Burkina Faso. Among lower-middle-income countries — those with US$1,000-4,000 per capita income — Nigeria, Pakistan and Egypt rank low, while others such as Sri Lanka, Ukraine and Indonesia rank much higher. Among upper-middle-income countries — those with US$ 4,000-12,000 per capita income — countries such as Malaysia, Costa Rica and China outstrip South Africa, Venezuela and Algeria.

“Among the high-income countries — those with US$12,000 and above — the variations are the greatest,” says the report. “There are strong performers such as the Nordics and Singapore. There are countries such as Qatar and UAE that are hubs for skilled and unskilled talent and rank in the upper half of this group, while countries like Russia, Greece and Kuwait fall near the bottom.”

The United States ranks 16th, a position “earned by its dynamic work force and capacity to attract talent, as well as its innovation potential and high levels of university-level education,” says the HCI. “Weaker factors include relatively high levels of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) during prime working ages and comparatively low levels of mental well-being.”

Ouch. But it’s a Swiss think tank speaking, so it must be true.

Among the trends and challenges identified by the HCI are some themes familiar to those down in the corporate and industrial trenches:

- “Many of today’s education systems are disconnected from the skills needed to function in today’s labor markets and the exponential rate of technological and economic change is further increasing the gap between education and labor markets.”

- “Current education systems are time- compressed in a way that may not be suited to current or future labor markets. They force narrow career and expertise decisions in early youth. The lines between academia and the labor market may need to blur or disappear entirely as learning, R&D, knowledge-sharing, retraining and innovation take place simultaneously throughout the work life cycle, regardless of the job, level or industry.”

- “Many large businesses, as one of the key consumers of human capital, face a skills mismatch between the jobs they need to fill and the people searching for jobs, a gap evident in many countries for which this data was available … Businesses increasingly place a premium on creativity, interaction and collaboration skills, yet the business community does not engage in directly influencing the formation of human capital as it does with other supply chains.”

- “Rapid demographic changes and the ability to forecast them offer a valuable opportunity for planning, while creating unprecedented pressures in markets and societies. Ageing [sic] economies will face a historical first as more and more of their populations cross the age of 60 and their workforces shrink further, necessitating a better integration of female workers, potentially importing talent and better aligning the state pension age with lifespans. Youth-bulge economies face burdens of a different kind as a very large cohort of the next generation — one that is more connected and globalized than ever before — enters the work force and with very different aspirations, expectations and worldviews than their predecessors.”

Full Translation

How do such indices themselves measure up, when it comes to translating rankings into real money? A glance at Asia serves to illustrate, in part because of the region’s diverse spread of wealth, with five high-income economies, four upper-middle-income countries, nine lower-middle economies and two low-income economies.

“In Asia, while Japan’s performance is strong across Health and Wellness, its relative weak spots include gender gap indicators for education and the work force, the country’s ability to attract talent and reported depression in the Well-being sub-pillar,” says the HCI. “After Singapore and Japan, Asia’s highest ranking countries are Malaysia (22) and Korea (23). China’s (43) positions across the four pillars vary greatly from the 26th rank on the Workforce and Employment pillar to 65th on the Health and Wellness pillar, the latter due in part to weak scores across the Health and Services sub-pillars.”

Among the HCI’s observations on the region:

Singapore: “Exceptionally strong scores across the qualitative education indicators and the high level of tertiary education among the adult population drive up its Education pillar ranking. Strengths on the Enabling Environment’s Collaboration and Legal framework sub–pillars include a top rank on the Doing Business Index. The Health and Wellness pillar is weakened mainly due to the burden of disease in the country.

New Zealand: “Despite the Enabling Environment being New Zealand’s (12) weakest pillar at 18th, the country also performs very well in some aspects, with top ten ranks across the Legal framework sub–pillar and a rank of 3 in Social mobility. New Zealand’s strengths in Education are similar to those of Singapore, but it ranks lower in the qualitative talent indicators on the Workforce and Employment pillar, including a particularly low rank (69) for the ability of the country to retain talent, or the ‘brain drain’ indicator.”

Australia and Malaysia: “Australia (19) and Malaysia (22) have almost identical scores on the Workforce and Employment and Enabling Environment pillars, but their performance within the pillars varies. Australia ranks poorly on its labor force participation of those over the age of 65, whereas Malaysia, the highest of the region’s upper-middle-income countries, ranks very low for the Economic participation gender gap indicator. Malaysia performs well on most of the qualitative talent and training indicators in the Workforce and Employment pillar. Australia performs well on the majority of indicators in Enabling Environment, in particular those concerning the legal framework. Australia also performs well on the Educational attainment of the population over 25 indicator.”

Republic of Korea: “The Republic of Korea (23) has its strongest performance on the Education pillar, with a rank of 17. Korea’s enrolment rates for tertiary education take the top spot overall and the educational attainment of the adult population has consistently strong ranks. Despite good scores across the qualitative indicators, overall Quality of the education system was particularly low at 52nd position. Korea’s scores on the Enabling Environment pillar are pulled down by low scores on the Social mobility and Social safety net protection indicators. Korea also has a notably low score on the Business impact of non–communicable diseases indicator, in the Health and Wellness pillar.”

Thailand: Thailand (44) also has a hugely varied distribution of rankings across the pillars, ranging from 27th on Workforce and Employment to 79th in Education. Thailand ranks 94th on the Enrollment in primary school indicator, and the majority of the education indicators are in the bottom half of the sample countries. Thailand’s very low levels of unemployment yield two top–five rankings for these indicators. Good performances on the qualitative talent indicators are also strong points.”

Indonesia: “Indonesia’s (53) ranks vary between 32nd on the Workforce and Employment pillar to 84th on the Health and Wellness pillar. A relatively low unemployment rate and good labor force participation of the over 65s, as well as a good performance on some of the qualitative talent indicators, support Indonesia’s strong overall performance on the Workforce and Employment pillar. Paradoxically, the country’s strongest performance overall is on the Well–being sub–pillar, with top and second rankings for the Depression and Stress indicators respectively.”

Philippines: “The Philippines (66) follows a similar profile to Indonesia with a 38th ranking on the Workforce and Employment pillar and 96th on Health and Wellness. The Philippines has top scores for the education and health gender gap indicators as well as a strong 15th rank for economic participation. Ranks below 100 on Well-being sub-pillar indicators pull down the aggregate Health and Wellness scores.”

Vietnam and environs: “Vietnam holds 70th position and Lao PDR holds 80th position. Bhutan’s (88) strong labor force participation and in particular low unemployment rates drive strong scores on the Workforce and Employment pillar. However, weak scores in technology absorption and training pull down the overall ranking to 74th spot.”

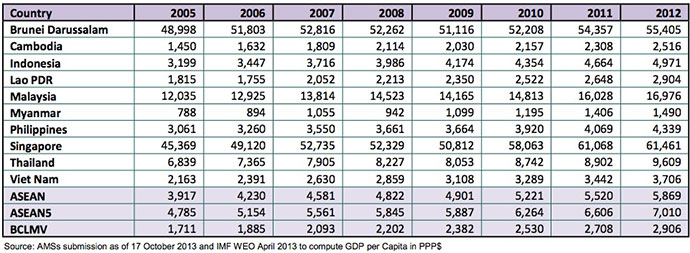

How does human capital stack up against real performance as measured by GDP? An October 2013 report from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) profiling GDP growth and the role of the services sector found that 2012 GDP growth was 5.7 percent, compared to 4.7 percent in 2011. Average income in ASEAN-5 (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) increased by 5.1 percent during the first semester of the year. And despite the effects of supertyphoon Yolanda, a December report from the Asian Development Bank still forecast that the economies of ASEAN-5 would grow by 4.8 percent in 2013. The table below shows how some of the countries examined by the HCI are performing in real-money terms.

“The ASEAN economies have found their niche in the services sector after deliberately moving away from agriculture over the last five years,” said the ASEAN report. “The services sector along with industry accounted for more than 80 percent of the GDP of most ASEAN economies. The share of services sector has continued to increase considerably in the region.

“In 2012, services sector accounted for the highest share of GDP in eight ASEAN Member States. Four years ago, the services sector was the main source of national income only in six ASEAN Member States, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, and Singapore. Brunei Darussalam, Thailand and Viet Nam were pre- dominantly in the industry sector, while Myanmar was concentrated on agriculture.”

The report also noted, “marked improvements in the economies of Philippines and Thailand have contributed significantly to the ASEAN5 GDP growth,” and that in terms of comparable international exchange rate, the purchasing power parity, “ASEAN’s GDP has expanded from PPP$2.19 trillion in 2005 to PPP$3.62 trillion in 2012.”

I’ll Be Your Mirror

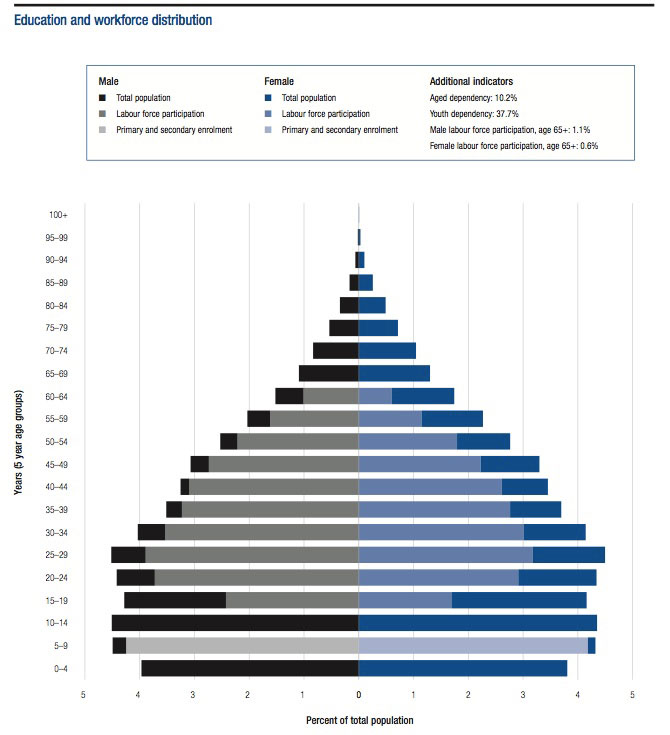

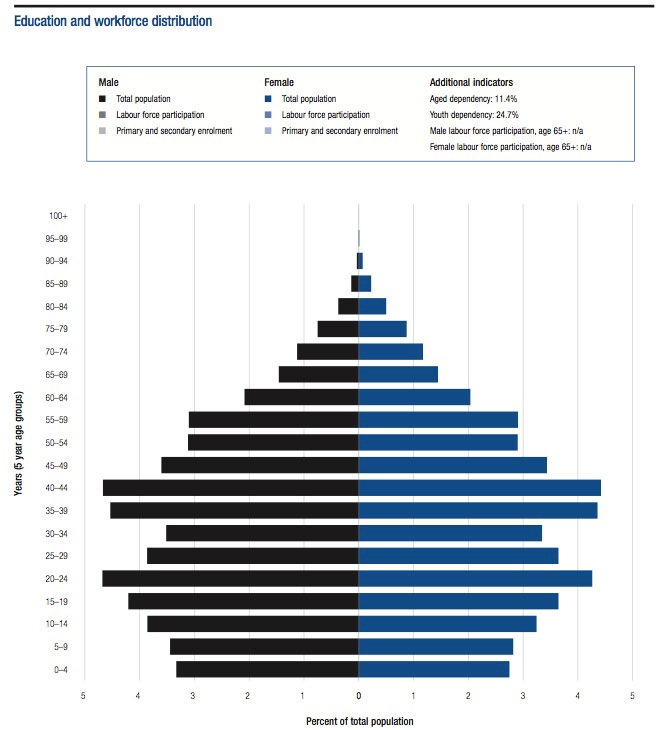

The bulk of the HCI is given over to 487 pages of country profiles for each of the 122 countries examined, showing via tables and graphs not only a country’s scores for every indicator and sub-indicator, but doing readers the favor of graphically breaking down education and work-force distribution by gender, enrollment and work-force participation, as well as pointing out that country’s percentage of aged dependency and youth dependency. Here, for example, are how Brazil (top) and China (below) shape up:

In the meantime, another index has surfaced that puts the World Economic Forum itself under the microscope.

The Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) at the University of Pennsylvania released its seventh annual 2013 Global Go To Think Tanks Report on Jan. 22 at a morning press conference in Washington, DC, hosted by the World Bank. Regional events took place in over 30 global cities to announce the report, which was translated into 13 languages including Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Hebrew, Hindi, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish.

“In the world filled with tweets and sound bites that are often superficial and politically charged, it is critical to know where to turn for sound policy proposals that address the complex policy issues that policymakers and the public face,” said James McGann, PhD, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program. “This Index is designed to help identify and recognize the leading centers of excellence in public policy research around the world.”

The Brookings Institution ranked top of the Global Think Tank list for the sixth consecutive year, followed by Chatham House (United Kingdom), Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (United States), Center for Strategic and International Studies (United States) and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI, Sweden).

Alas, it is our solemn duty to report that, among the globe’s 6,826 think tanks, the World Economic Forum ranked No. 39 in 2013, a precipitous fall from No. 35 a mere one year ago.

Say rankings-weary governments around the world, “Put that in your Swiss pipe and smoke it.”