A new age is dawning for space travel. Companies are clamoring to get a piece of what likely will become very big action as NASA turns over much of its prior Earth-orbit initiatives to the private sector.

That bodes well not only for the companies that will win government contracts stemming from NASA’s Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) initiative, but for the state of Florida as well, as it struggles to reshape and rejuvenate what had been flagging economic development efforts.

The changes in focus and effort are in response to the fact the NASA’s shuttle program is no more. The final space shuttle mission ended July 21, 2011, when Atlantis rolled to a stop at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Thankfully, the public and private sectors were planning ahead. Space Florida, a state economic development agency, was created in 2006 with the thought in mind that more could be done in building upon the aerospace industry presence. And NASA put out word in the fall of 2009 that it wanted to pursue a commercial crew program.

But the biggest event in this transition period came on Oct. 31 when Boeing announced that it would consolidate its commercial crew program at the Kennedy Space Center.

What that means is that Boeing will be taking over one of NASA’s old space shuttle hangars to manufacture the Crew Space Transportation (CST)-100, a reusable, capsule-shaped spacecraft designed to ferry seven people into orbit in four or five years.

To knowledgeable observers on the ground, Boeing’s announcement portends something much greater than the immediate job creation, although any job gains are welcome in Florida’s aerospace industry, which is estimated to have lost between 4,000 and 6,000 jobs with the shuttle program’s demise.

Boeing expects to create 550 high-tech jobs at Kennedy Space Center over the next four years, 140 of them by the end of next year. But the company’s announcement represents much more than a singular deal. Rather, it is the first of what is expected to be a future wave of aerospace companies that will be investing in the state, either by expanding existing operations or establishing new operations.

“We are entering a new era where NASA will have a new rocket system for deep space exploration, a new capsule, which will be built in Florida, and a future reliance on commercial players,” says Frank DiBello, president and chief executive of Space Florida, which helped broker and sponsor the deal with Boeing. “You will clearly be hearing more announcements about expansions and relocations.”

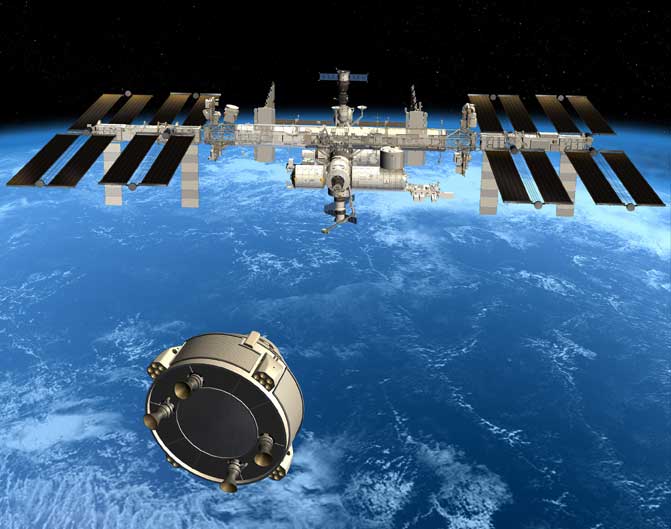

At the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, California-based SpaceX has already launched an unmanned version of its crew vehicle into orbit and recovered it safely. The company has won a US$1.6-billion contract with NASA for a dozen unmanned cargo runs to the space station, with the possibility of manned flights to follow.

Virginia-based Orbital Sciences, Washington-based Blue Origin and Nevada-based Sierra Nevada are also battling for NASA’s business, and all of them have ongoing relationships with Space Florida, DiBello says.

NASA is counting on these companies to ferry cargo and astronauts to and from the International Space Station in three to five years. Until then, the space agency will continue to shell out tens of millions of dollars per seat on Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

“They [NASA] are truly depending upon the evolution of the commercial marketplace,” DiBello says. “NASA is basically looking at an era in which it will acquire space flight services on a commercial basis. That is what this program is about.”

The big selling points for Florida — noted by Boeing executives — are the ample and veteran aerospace work force nearby and the vast infrastructure offered to the company essentially at no cost, part of an incentive package valued by state officials at $50 million.

As part of its agreement with Space Florida, Boeing takes control of several empty buildings at the Kennedy Space Center, including an Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF), a 128,000-sq.-ft. (11,891-sq.-m.) hangar and office building, where the company will design and build a crew vehicle that it says will be ready for a test flight by 2015.

The company will also take over the Processing Control Center, 99,000 sq. ft. (9,197 sq. m.) of control rooms and office space to be used to support mission operations, training and program offices. As part of the no-charge, 15-year lease agreement, Boeing will modernize the facilities to provide efficient production and testing operations.

The fact that the buildings are a part of Kennedy Space Center was also a selling point for the company because they provide close proximity and practically immediate access to the company’s main customer NASA. So the combination of experienced work force, access to substantial infrastructure (the buildings) and close proximity to customer made business sense for Boeing.

“Our goal is to be efficient and affordable, and one of the ways that we can do that is to locate as many aspects of our program as we can into one location. That was one of the main reasons why we decided to locate there,” said Chuck Hardison, Boeing’s Commercial Crew Production and Ground Systems Manager at KSC.

‘Sea Change’

The Economic Development Commission of Florida’s Space Coast worked closely with a team comprising Space Florida, Brevard County, Enterprise Florida and Brevard Workforce and NASA Kennedy Space Center to develop the winning proposal for the Boeing project, which began 18 months previous when the company requested a project proposal.

There has been no published value of Boeing’s investment. However, Gray Swoope, head of Enterprise Florida and a leading voice for what has been aggressive reform within the economic development community there, places the value of the project at $163 million.

Also, no breakdown on the $50-million incentive package has been made public. Certainly, there is a value of the no-charge lease arrangement, and Swoope said the company would qualify for a capital income tax credit that could be sustained for nearly 30 years.

In 2010, Boeing contributed over $138 million to the Space Coast economy, says the EDC. At full employment, the projected economic impact of the CCTS program will be approximately $61 million.

Swoope, previously head of the Mississippi Development Authority, was hired by newly elected Gov. Rick Scott in February, and has brought an aggressive-pursuit style of economic development that had not been seen in Florida in recent years.

“It’s been has been a challenge here but we’re moving in the right direction,” Swoope says.

Neal Wade, previously the head of the Alabama Development Office, has a similar philosophy to Swoope in aggressive recruiting and dealmaking. Wade now heads economic development for the St. Joe Company, the largest single private landowner in Florida.

“We have had a sea change in the economic development approach in this state,” Wade says. He says the Boeing announcement affirms that Florida remains a vital part of an aerospace corridor in the Southeast.

“Boeing announcement is huge for the entire region because it demonstrates what a strong aerospace corridor we have in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and into Florida. So this underscores that this is now the fourth largest aerospace corridor in the world,” Wade said.

Wade said because of its size and scope, the Boeing project will have a ripple effect, strengthening existing aerospace suppliers and bringing in new ones.

That fact was not lost on DiBello, whose agency’s mission is to strengthen the industry within the state.

“For each major relocation that we get for a product like the CST-100, there is a supply chain that we have to aggressively seek to put in place,” DiBello says. “Frequently, the supply chain availability is one of the elements of the business environment that is an attraction point and a criterion that companies use. So we are working aggressively on strengthening Florida’s aerospace supply chain.”

The Obama Administration requested $850 million in NASA’s 2012 budget for the commercial space effort. The House slashed that to $312 million, but the Senate got it to $500 million.

Boeing expects to start removing shuttle platforms and modifying the buildings that it will take over in the next few months. To those who have said the space program is dead and that Kennedy Space Center is going out of business with the retirement of the shuttle program, DiBello takes issue and points out a salient fact.

“Many people have talked about the end of the shuttle program being the end of the space program. But on the day that the shuttle flew its last flight and launched from the Kennedy Space Center on its last mission, there were six other launch vehicles on pads at the Cape,” DiBello says. “The space program is anything but over.”