In a 2014 op-ed piece in The Baltimore Sun, then Maryland Secretary of Planning Richard Eberhart Hall wrote, “Redevelopment provides environmental benefits by reinvesting in buildings and infrastructure, focusing growth where services exist rather than creating new development on tracts far from population centers. People know it when they see it: downtowns bustling with activities and special events, a variety of housing types near places of employment, wide sidewalks that beckon to pedestrians and well-tended storefronts.”

He could have been describing plans for Port Covington, a sweeping, 260-acre (105-ha.) project that will transform a former industrial site into a vibrant live-work-play space. The mixed used project calls for offices, residential, retail, a whisky distillery and loads of parks and green space. Transit is an integral part of the Master Plan with proposed extension of Light Rail, bus and water taxi stops. The entire project will take about 20 years to complete. The centerpiece of the redevelopment is the 50-acre (20 ha.), 3 million-sq.-ft. (278,709-sq.-m.) campus and headquarters for Under Armour, the high-performance sportswear company founded by Kevin Plank, the company’s CEO and unabashed Baltimore booster.

Generating Some Buzz

“You can see the property from I-95, when you pass the stadium on your left,” says Neil Jurgens, vice president of Global Corporate Real Estate for Under Armour. “Right now you see the Baltimore Sun printing press building; we’re just beyond that. It’s great because at night you see our building really well. Our Master Plan calls for three towers that will be visible from the interstate. Kevin really wanted to create this iconic place for Baltimore. He said, ‘Let’s not only create a great place for our teammates but also generate great buzz for the city. Let’s make a new front door.’”

While the larger project is being developed by Plank’s private development company, Sagamore Development, the Under Armour project is separate. “We’re owning it and developing it ourselves,” says Jurgens. That separation is important to the company as Sagamore pursues such items as tax increment financing (TIF) for any infrastructure improvements to the real estate. “Like anyone else, we are going to pursue the as-of-right tax credits, the brownfield tax credits and the enterprise zone,” he says. “But we’re not using any TIF to fund the construction of the Under Armour campus itself. That sort of money will not, and couldn’t, be used for building our field house or our buildings.”

The Under Armour campus will be built in four primary stages of development which are broken down into smaller phases. “My phasing plan is 12 phases, which might sound crazy but they’re manageable pieces,” Jurgens says. “We’re still a growth company. Those twelve phases of development can be accelerated if the company grows faster. We will have the ability to slow down or speed up depending on Under Armour’s performance, something happens in the world, whatever.”

At this point in the process, Under Armour has received approval from the city’s Urban Design and Architecture Review Panel (UDARP). The next step is to go before the city’s Site Plan Review Committee. “This first phase that we’re in now is substantial, developing 500,000 sq. ft. [46,451 sq. m.] of space, plus the parking structure, plus the lake, plus the central utility plan and some other things,” says Jurgens. “To put it in perspective, our existing campus at Tide Point is just under 500,000 sq. ft. We just opened this building, an adaptive reuse of a Sam’s Club, and we have 170,000 sq. ft. [15,794 sq. m.]. The expectation is that we’ll build it in the next four to five years.”

Jurgens called the project a game changer for the city and in this instance the well-used description is not an exaggeration. As it stands now, Port Covington isn’t generating tax revenue or jobs. Under Armour is planning for a campus with 10,000 employees. Consider the following statistics: currently Under Armour has approximately 1,800 employees with just under 40 percent living in the city limits.

“They’re buying homes, renting apartments, buying food, all their goods. The economic uplift is huge,” Jurgens says. “We had Ernst & Young do an economic study and they found that for every Under Armour job being generated here at this campus, another 1.5 jobs are being generated. That’s from other businesses, vendors, suppliers, companies supporting Under Armour’s operation. And those people are spending. There’s enormous economic impact to the state. We’re taking this forgotten area, this underutilized land, and really transforming it into a vibrant economic engine for the city.”

Under Armour has invested in facilities around the world, but there was never any doubt that the company’s headquarters would go anywhere but Baltimore. Though he doesn’t claim to speak for his boss, Jurgens — also a Baltimore native — can certainly identify with Plank’s vision of making something great happen in Baltimore. It’s why, when he was living in California working for Disney, Jurgens made the move back east. “It was his vision about what the company was going to become and what he was going to do to help the city,” says Jurgens. “It was a compelling story, a compelling vision that brought me back, for sure. We’ve built all over the place. But we see the core, the nucleus here in Baltimore. We call it home.”

Startup City

Comments like Jurgens’ are music to the ears of Bill Cole, CEO of the Baltimore Development Corporation (BDC). Cole loves to tell the Baltimore story, especially enumerating the city’s many assets — a great location, easy access via interstate, rail and air, and a first-class deep water port. But excellent infrastructure tells just one side of the surge of interest in Baltimore.

“We’re the 4th fastest growing millennial population in the US and we have the 8th largest millennial population overall,” Cole says. “You add in Under Armour, you add in John’s Hopkins University, the University of Maryland and two rapidly growing bio-parks and all of a sudden you have this young vibrant workforce. A lot of things drive our millennial growth but by all relative terms living in an urban area, this is still one of the less expensive areas up and down the East Coast. It is exponentially cheaper to live here than in Washington, D.C., so we also see a lot of people who choose to live here and commute using the train.”

degrees among the 25 largest metros.

Baltimore is an acknowledged startup city. The US Chamber of Commerce ranks Maryland no. 3 in the country for innovation and entrepreneurship, thanks to the state’s longstanding commitment to nurturing research and development in bioscience, cybersecurity and other tech fields. The BDC has long supported early stage tech companies through its Emerging Technology Centers (ETC) initiative, which provides technical and networking connections to help those companies grow. The ETC has an outstanding track record, assisting more than 350 companies since 1999, 87 percent of which are still in business. The companies have created more than 2,300 jobs and raised $1.8 billion in outside funding.

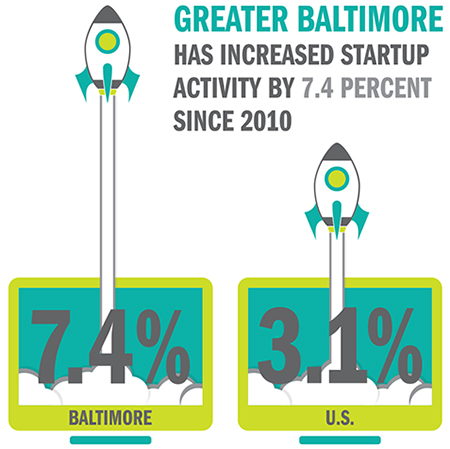

Based on statistics from the 2015 Greater Baltimore Regional Report published by the Economic Alliance of Greater Baltimore, there appears to be a correlation between startup activity and a city’s millennial population. Looking at data from 2010 through 2015, startup activity doubled in Greater Baltimore as the metro also experienced some of the nation’s fastest growth of young professionals with advanced degrees.

But startups and tech companies aren’t the only ones to call the City of Baltimore home. Pandora, the Danish jewelry company, moved its regional headquarters along with 250 employees from the suburbs to the downtown core in 2015. The company looked at more than 60 locations and acknowledged that employees were eager to work in the urban environment. And energy company Exelon is continuing to build its $270 million Exelon Tower headquarters building and mixed use development. It is scheduled to open later this year.

A Blank Slate

Not all redevelopment involves greenspace, whisky distilleries and residential. The massive Tradepoint Atlantic is the brownfield redevelopment an old Bethlehem Steel mill at Sparrow’s Point, looking to turn 3,100 acres (1,255 ha.) into a “world class, institutional quality, multi-modal industrial development,” says Mark Levy, managing director at JLL, the exclusive real estate provider for the property.

In addition to its size, the Tradepoint property boasts outstanding transportation infrastructure including a short-line railroad connecting to two Class 1 railroads and easy access to the Port of Baltimore, major interstates and an international airport. Levy says the sheer scope of the land and infrastructure at Tradepoint Atlantic make it an exciting venture. “I don’t think we have any preconceived notion of what is right or wrong for the property,” he adds. “The list of things we won’t look at is probably shorter than the list of things we will look at. In the industrial spectrum, there’s really nothing that’s been put on the ‘do not pursue’ list.”

In January 2016, FedEx Ground became the first company to sign on at Tradepoint Atlantic. The small-package ground delivery unit will build a 300,000-sq.-ft. (27,871-sq.-m.) distribution facility at the property. “In a macro sense, FedEx Ground is essentially a distribution network for a lot of companies that are potential candidates for the property,” says Levy. “They realize the opportunity for the larger property and realize the opportunity to be proximate to what the future could hold here.”

Tom Sadowski is the CEO of the Economic Alliance of Greater Baltimore. He says projects like Tradepoint Atlantic, Port Covington and the Under Armour headquarters are indications of not just Baltimore’s strength, but the region and the state as well. “We have some of the most tremendous and diverse arrays of government and federally funded laboratories, institutions, military installations that are driving the nation’s economy, from healthcare and health-related research to cybersecurity and aerospace,” he says, noting a change in Maryland in the past four to five years. “We’ve stopped relying on federal spending and looked for innovative and entrepreneurial ways to leverage our assets to create real sustainable commercial enterprise and commerce here,” he says.

JLL’s Levy agrees. “The success of Tradepoint Atlantic is going to be predicated on this being a strong public private partnership,” he says. “A lot of the success of these types of projects has to do with the commitment on the part of the state to get behind it and make it a success. Historically, Maryland hasn’t been favorably viewed in the context of site selection, not viewed as pro-business or putting the right incentives in place to attract business, but I will tell you that when the Secretary of the Maryland Department of Commerce gives you his cell phone number and says call me anytime, something’s different. I have never in my life called a cabinet level government official and had him answer the cell phone. This is a great confluence of that sort of political infrastructure. This is not the Maryland of 15 years ago.”