Sometime later this year, a century-old rail bridge that crosses the Mississippi River at St. Louis is expected to reopen after a four-year transformation. Originally opened in 1899, the Merchants Bridge is a key link in one of the primary East-West rail corridors in the country, leading into and out of the nation’s second-largest freight rail interchange. Antiquated as the structure had become, it could support but a single train at once, thus creating bottlenecks on both the Missouri and Illinois sides of the Mississippi. By restoring Merchants Bridge to full viability, the $222 million project will essentially double its capacity.

“It’s a big win for the St. Louis area, but also for the national supply chain,” says Mary Lamie, executive of St Louis Regional Freightway. The new Merchants Bridge, she says, “will increase our ability to take on more freight and bolster our ability to serve as an alternative during supply chain disruptions.”

Courtesy St. Louis Regional Freightway

“We are very bullish on this market.”

— Wakeel Rahman, VP of Acquisitions, NorthPoint Development

The Merchants Bridge restoration tops the annual list of priority infrastructure projects the Freightway released in May. The list includes plans for 25 transportation improvements representing combined investments throughout the St. Louis region of some $3.8 billion. Priority projects cover multiple transportation modes including rail, road, air and ports, part of a collective push to bolster the region’s profile as a Midwest axis of logistics.

“Saint Louis,” believes Chester Jones, “is primed to take its place as a global hub for logistics and the movement of goods throughout the United States and internationally.” Jones, head of supply chain operations for O’Fallon, Missouri–based commercial refrigeration company True Manufacturing, sees the investments being sunk into infrastructure as more than just a boon to his transportation fleet.

“Ultimately,” Jones tells Site Selection, “infrastructure improvements attract more business and create growth. That benefits our company strategically.”

Playing Catch-up

Lamie ticks off the region’s logistics assets like a mantra: Central location; six Class I railroads; four Interstates; two international airports; a robust port system along the Mississippi. The Freightway, established in 2016, is a key player not merely in supporting industries reliant on infrastructure, but also in promoting the manufacturing logistics cluster within the St. Louis metro and seven adjacent counties in Missouri and Illinois.

“From the manufacturing logistics perspective,” Lamie says, “our growth rate didn’t rebound after the Great Recession as perhaps it should have. When we looked at our sister cities like Kansas City, Memphis, Columbus, Indianapolis and Nashville, their growth rates were better than ours. We essentially grew out of a transportation study that found that we were being outhustled from a marketing standpoint.”

Since its creation, Lamie says, the Freightway has “secured an immense amount of infrastructure dollars” — including $700 million over the past three years from the Missouri and Illinois transportation departments — and coordinated efforts spanning multiple jurisdictions where projects are in the planning and construction stages.

The Freightway’s Priority Projects list includes investments totaling more than $133 million along I-70 between St. Louis and Kansas City, one of the nation’s most heavily traveled freight corridors. Key economic drivers along I-70 as it passes through the St. Louis region include the General Motors Wentzville facility, Boeing’s St. Louis facility, St. Louis Lambert International Airport and multiple fast-growing industrial sites. True Manufacturing’s O’Fallon headquarters is located just off the highway.

“We often say,” Jones relates, “that I-70 is the heartbeat of True Manufacturing. We traverse it with about 88 trucks a day going between our headquarters and our manufacturing facilities.”

Industrial Activity Surges

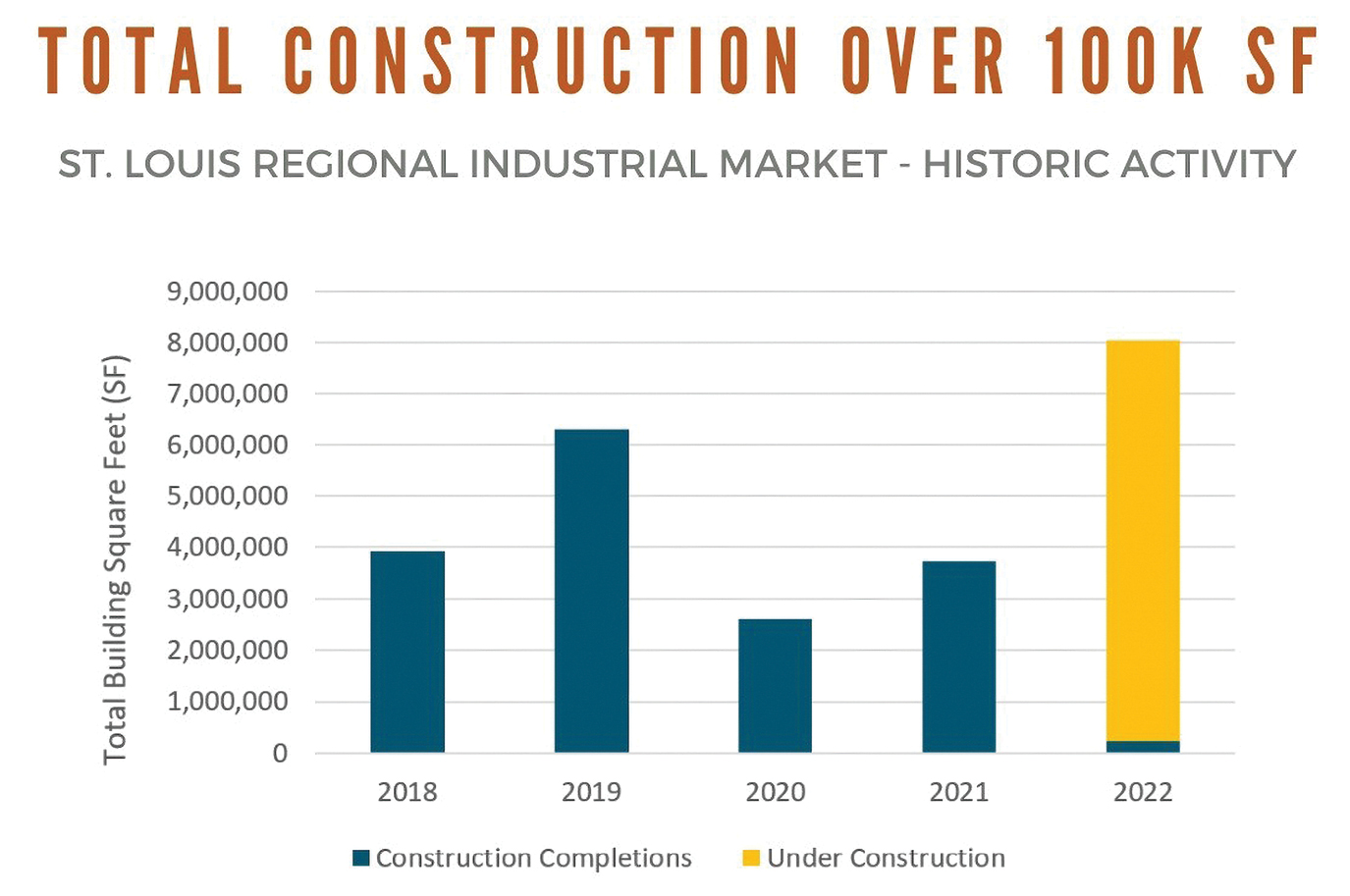

As infrastructure improvements unfold along major arteries such as I-70, the St. Louis region’s industrial real estate market is growing to meet the parallel demand for modern bulk and manufacturing space. Speculative construction activity, according to a Freightway report released in May, stands at a record 7.8 million sq. ft., higher than in the three previous years combined.

“It’s developers stepping up to meet unprecedented demand,” says Wakeel Rahman, vice president of acquisitions at Kansas City-based NorthPoint Development, which constructs, manages and leases industrial properties nationwide. NorthPoint’s logistics assets in the region, says Rahman, include 12 million sq. ft. of industrial properties either built or under construction.

“We are very bullish on this market,” Rahman tells Site Selection. “In terms of macro and micro factors, it has a lot going for it, with 12 to 15 months of runway. Infrastructure projects,” he adds, “are a huge driver of what we do. If you can unlock new submarkets and other new development opportunities because there’s a new infrastructure project either in tow or under construction, that makes a real difference.”

In addition to the growth along the I-70 corridor, the Freightway’s real estate report highlights industrial development connected to Illinois Route 3, a 60-mile manufacturing and logistics corridor along the Illinois side of the Mississippi that is part of the Freightway’s coverage region. The Route 3 corridor is home to more than 6,000 businesses, and, according to the report, its manufacturing and logistics sectors generate more than $16 billion in annual revenues and support more than 221,000 jobs. Lamie says the Illinois Department of Transportation has supported the corridor with more than $20 million of funding over the last several years.

“The secret to the success along Route 3,” she says, “is the infrastructure that’s in place. Intermodal and rail yards provide connectivity, and you’re in close proximity to the Mississippi River.”

There’s an “immense demand,” says Lamie, for industrial space along Route 3, as well as the potential to develop it.

“We have a series of industrial sites in that region and available locations for growth. There’s vacant industrial land that has close proximity to multimodal transportation that is not quite developer-ready. We’re identifying those sites and trying to take on some of those challenges so we can move the needle and move them to developer-ready.”

Leveraging the Big Muddy

Among the most intriguing projects presently in the works is the planned upgrade of a port on the Mississippi that would serve as an anchor of a new cargo route that would connect St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico. The Missouri legislature recently earmarked $25 million toward transforming the port at Herculaneum as the northern terminus for a fleet of LNG-powered vessels capable of moving containers up and down the Mississippi. Goods would move between Herculaneum and a port being built in Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish faster and in greater volume than on present-day barges.

The so-called Super Hub could be a means of linking the Midwest to ports around the world.

“Given the supply chain disruptions we’ve seen over the past two years and the continuing congestion at ports on the West Coast, there is no question that shippers need alternatives,” says Lamie. “Our freight advantages,” she adds, “are fueling this new opportunity to elevate the Mississippi River’s role in global trade. Everyone recognizes,” she says, “that it’s underutilized and that this is a big opportunity.”

Texas-based Hawtex Development Corp. was announced in December as lead developer of the project, whose projected cost is some $86 million. The company says it hopes to have the facility operating by the end of 2024.

“It’s very interesting to us because it opens up another option,” says Jones of True Manufacturing. Typically, he says, the company exports to Europe via ports in Norfolk and New York and to Asia from the Port of Long Beach, California, all of which backed up at the height of the pandemic.

“This could give us the opportunity,” he says, “to actually go south — float products down to Louisiana and put them onto a big boat there. This would give us that other option, and this business is all about options.”