STRENGTHENING ARKANSAS’ DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Last week, AVAIO Digital Partners announced a future data center campus, dubbed AVAIO Digital Leo, will situate itself just outside of Little Rock, Arkansas, in Pulaski County. The fresh $6 billion investment is the largest economic development investment in state history and will deliver an estimated 500 full-time jobs once complete. The initial investment is said to cover the project’s first phase, as total investment into the campus could reach upwards of $21 billion. “It is our intention that this extraordinary 760-acre site in the Little Rock area will be both a major pole of data center capacity and an engine of sustained economic and technological momentum for Arkansas,” said AVAIO Digital CEO Mark McComiskey. AVAIO plans to construct the campus in multiple phases, with the first of these phases expected to come online by mid-2027. Construction will kick off within the next few months, resulting in thousands of new construction-related roles. Entergy Arkansas has been contracted by the company to supply an initial 150 megawatts of power to AVAIO Digital Leo, although the campus will grow to demand 1 gigawatt of power as future facilities begin operations.

Photo courtesy of Johnson & Johnson

J&J INJECTS NEW OPERATIONS INTO THE TAR HEEL STATE

Pharmaceutical manufacturer Johnson & Johnson is doubling down in North Carolina, announcing its third major investment in the state since 2024. The company has said it will deliver a new multibillion-dollar manufacturing facility in Wilson, located along I-95 about 40 miles east of Raleigh, to produce medicines that target oncology and neurological diseases. This new site will join the company’s $2 billion pharmaceutical manufacturing campus still under construction in Wilson following its initial 2024 announcement. “This new facility is the third North Carolina project announced by Johnson & Johnson in the past year and will help to further accelerate the delivery of our portfolio of transformational medicines for patients,” said Johnson & Johnson EVP and Worldwide Chairman, Innovative Medicine, Jennifer Taubert. “North Carolina is an important life sciences hub, and we look forward to increasing our presence in the state.” The new facility is anticipated to create an additional 500 direct jobs in the region. Johnson & Johnson’s project investment will be supported by a $12 million legislative appropriation to expand Wilson Community College’s training center. See Site Selection’s September 2025 report on North Carolina’s life sciences momentum.

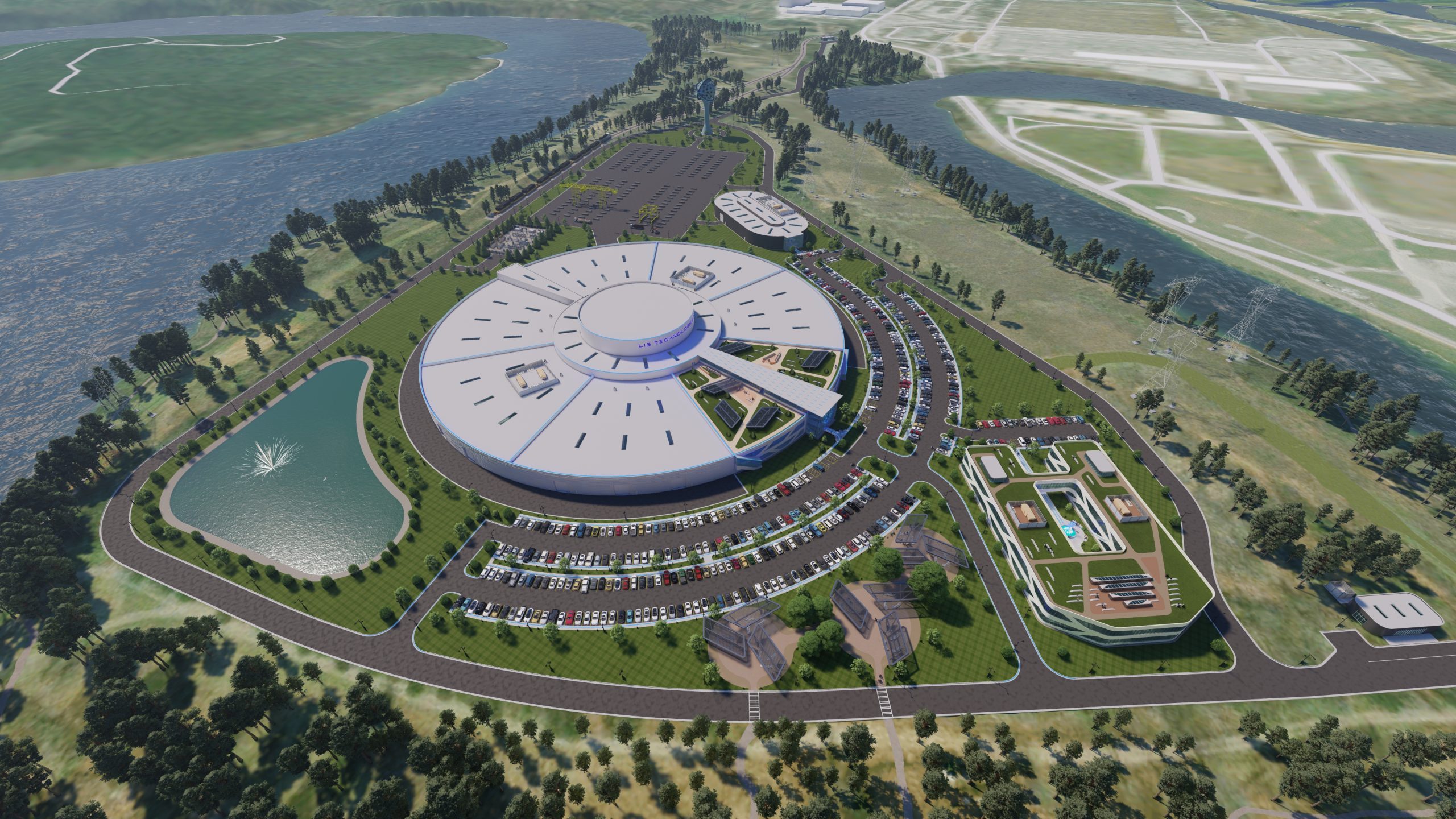

Rendering courtesy of Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development

TENNESSEE’S LANDS THIRD LARGEST NUCLEAR INVESTMENT

Site Selection recently highlighted nuclear activity finding its place in eastern Tennessee’s city of Oak Ridge, and it’s clear the momentum isn’t dying down anytime soon. Last week, LIS Technologies joined Governor Bill Lee to announce a new $1.38 billion uranium enrichment site in the city. The advanced laser technology developer plans to introduce the world’s first U.S.-origin commercial laser uranium enrichment plant. These operations will be vital to supporting U.S. utilities, reactor developers and the defense industry and strengthening the nation’s nuclear fuel supply chain. “Selecting Oak Ridge is both a strategic and symbolic decision for LIS Technologies. This community represents the foundation of America’s enrichment capability and the future of its clean energy and national security mission,” said LIS Technologies Executive Chairman and CEO Jay Yu. “Our laser enrichment technology fundamentally changes the economics of enrichment, enabling faster deployment, lower capital intensity and long-term cost advantages. With our NRC licensing process underway, we are moving deliberately toward construction readiness and positioning the U.S. to lead the world in commercial laser enrichment.”

Reports compiled and written by Alexis Elmore