“There’s a need for a pile of nitrogen in North Dakota.”

So said Don Pottinger, CEO of Northern Plains Nitrogen (NPN) in announcing in May the choice of Grand Forks, N.D., in the famously fertile Red River Valley, as the location for a new $1.5-billion fertilizer plant that will employ 135.

The NPN project was conceived to provide a secure supply of nitrogen based fertilizer for the growers in the North Central United States and the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. These growers are largely supplied with nitrogen based fertilizer products imported from countries such as Egypt, Oman, Qatar, China, and Saudi Arabia.

The plant could open as early as spring 2017, producing 2,200 tons per day of ammonia plus urea and urea-ammonium-nitrate.

Larry Mackie, NPN’s COO, has more than 43 years of experience in nitrogen plant development and plant operations. In an interview, Mackie, a Winnipeg native who worked for 24 years for Simplot, says freight sensitivity is the first thing to address when picking a fertilizer plant site, because “you buy it by the ton. So we want to build in the market.”

Next comes water, as the plant will consume 4,000 gallons per minute. Then there’s natural gas and transportation proximity. Natural gas accounts for about 80 percent of the cash production cost for ammonia. Today much of the natural gas from the feverish oil shale activity in western North Dakota’s Bakken oil field is still flared off, or “stranded” in industry parlance. But work is under way to start harvesting that stranded resource in order to feed harvests of the agricultural variety.

“Our plant is immediately adjacent to the BNSF railroad,” says Mackie in a phone interview. “You have Highway 29 going north-south and Highway 2 going east-west. And we’re utilizing Grand Forks’ wastewater. We’ll make angel’s tears out of wastewater, making good use of something that would otherwise be disposed of. There’s a 69-KV line and a 230-KV line, and several gas lines are within reach. And you want to be by a good-sized community for a work force. The Grand Forks community is absolutely awesome for that. They have a high work ethic, and are just good hardworking people.”

Mackie says his team considered South Dakota too. “But it’s pretty tough to beat Grand Forks. The Grand Forks economic development folks leaped tall buildings for us, as did all the [City of] Grand Forks staff, the mayor and the governor.”

Mackie says his team is fielding “very strong interest” from local growers, and is in discussions with “several players in the industry” as finance partners.

Harmonic Convergence

The NPN project follows last September’s announcement of a similar plant being planned by CHS Inc. (formerly Cenex), the nation’s largest farmer-owned cooperative, in Spiritwood, N.D., east of Jamestown along I-94. That project would bring an investment of between $1.1 billion and $1.4 billion, and would rise on a 200-acre parcel near a 1,100-MW combined heat and power plant owned by Great River Energy, less than a half-mile from one of Cargill’s largest malting plants in the world.

“Today CHS imports fertilizer products from 19 countries,” said CHS President and CEO Carl Casale last fall. “Developing additional domestic crop nutrients sources closer to our customers is critical to meeting demand, improving our logistical and distribution expertise, and adding value for the farmers who count on us.”

Preliminary plans call for building a plant that will produce 2,200 tons of ammonia fertilizer daily. It will be distributed as anhydrous ammonia, urea and UAN liquid fertilizer to farm supply retailers and farmers in the Dakotas and parts of Minnesota, Montana and Canada. The proposed plant will take advantage of abundant regional natural gas feedstock. It will employ between 100 and 150 people, with a tentative start-up in the second half of 2016.

CHS is in discussions with Great River Energy and the Jamestown Stutsman Development Corporation (JSDC), which together own the Spiritwood property, to formalize project agreements related to the land and services to be provided by Great River Energy and JSDC. CHS will continue working with Gov. Dalrymple’s office, the North Dakota Department of Commerce, JSDC, Jamestown city officials, Stutsman County, North Dakota Farmers Union and Great River Energy to move the project forward. In addition, CHS has contracted with the engineering firms of CH2M Hill of Houston, Texas, and Kadmas, Lee and Jackson of Bismarck for on-site planning and related business and construction details.

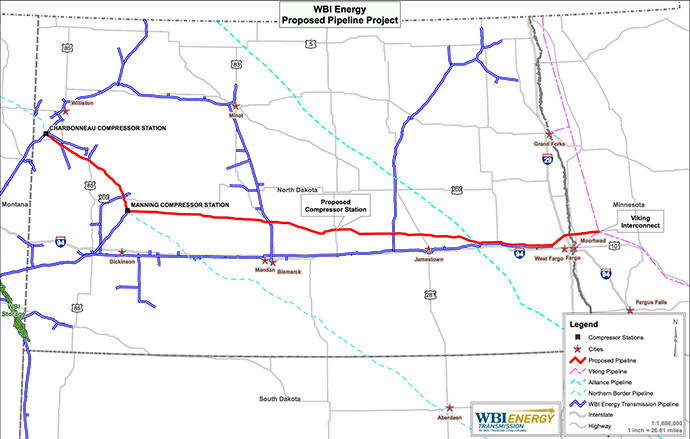

The site is also near the proposed route of a new natural gas pipeline from WBI Energy, Inc., the pipeline and energy services subsidiary of MDU Resources Group, Inc., that would stretch from the oil patch of far western North Dakota to western Minnesota where it would connect with Viking Gas Transmission Company’s pipeline system. Announced May 30, the project would provide a new transportation route to bring Bakken-produced natural gas directly to industrial customers and commercial and residential utility customers in eastern North Dakota.

The pipeline has been initially designed to transport approximately 400 million cubic feet per day of natural gas and, depending on user commitments, could be expanded to more than 500 million cubic feet per day. The project investment is estimated to be between $650 million and $700 million. Following receipt of capacity commitments and necessary permits and regulatory approvals, construction on the new pipeline would begin in early 2016 with completion expected by late 2016.

“Since 2010, we have invested over $150 million in energy development projects in North Dakota including our acquisition of midstream assets near Belfield and the Dakota Prairie Refining diesel plant currently under construction near Dickinson,” said Steven L. Bietz, president and CEO of WBI Energy. (Another $450-million refinery from three Native American tribes just broke ground in April south of Minot). “This project would be the largest single pipeline construction project in our company history. This project, combined with other recent and ongoing projects, would bring our total Bakken-related investment to nearly $1 billion.”

That’s a lot of billions floating around.

John Mittleider, manager of ag and bioenergy development in the economic development & finance division of the North Dakota Dept. of Commerce, says both the CHS and NPN fertilizer plant projects came onto the radar about a year ago. His team helped convene discussions and bring logical sites to the table that could qualify for the projects’ high water and natural gas requirements.

“We’ve helped connect them to other players in the state that could supply their inputs,” he says. In addition to looking at grant funding to help both projects through their front-end engineering and design (FEED) studies, he says, Commerce is also identifying potential incentives and evaluating roadbed and other infrastructure improvements that could be facilitated by the state. The first phase of the CHS FEED study is a $10-million investment from the co-op.

“A lot of money is spent doing the analysis,” explains Mittleider. “It’s a long-term process before there’s actually dirt dug. Both are moving along quite nicely at this time.”

‘About Time’

The two billion-dollar bets would join a bevy of announced and under-construction fertilizer plants in such locations as Louisiana and Iowa over the past year. But a scan of fertilizer production locations across the U.S. reveals a dearth of such plants in the Dakotas, where legume and other crops are grown in huge volumes and shipped all over the world. North Dakota growing operations alone use more than 1 million tons of fertilizer annually — more than one of the proposed plants can produce. There is some anyhydrous ammonia production at the Great Plains Synfuels plant operated by Basin Electric Power Cooperative’s Dakota Gasification Co. near Beulah, and the next closest fertilizer production site is in Manitoba.

Asked what the agricultural community across the state thinks of the pending projects, Mittleider says, “Farmers I’ve heard from say it’s about time we get a fertilizer plant built. They’re excited to see these projects move forward. It would be a huge positive for farmers — right now a lot of the fertilizer comes in from overseas, and there’s at least a 90-day lag between time of order and time it’s issued. Having fertilizer locally would be a critical positive for our growers. A lot of that has to come from overseas and has to be shipped up the Mississippi River. If you get droughts, or any constraints with barge traffic, or weather-related issues, obviously fertilizer deliveries can be delayed. We’ve seen that occur in the past.”

But the opportunity goes well beyond just North Dakota, says Mittleider, including potential customers in South Dakota, Iowa, Montana, Minnesota and Canada.

“Look at a map of where fertilizer facilities are located today, and we certainly are in a deficit area,” he says. “And with all the oil and natural gas in the western part of the state, we have a huge opportunity to bring gas directly into these facilities. The demand is here, the gas is here, the market’s here.”

Those were the conclusions of an agribusiness diversification study for a four-county region in northeastern North Dakota that was prepared last year by Grand Forks-based national economic development and policy think tank Praxis Strategy Group on behalf of the Grand Forks Region Economic Development Corporation, and backed by the North Dakota Agricultural Products Utilization Commission.

Mark Schill, vice president for research at Praxis and managing editor of NewGeography.com, says while ag is a huge part of the region’s economy, it hasn’t necessarily resulted in major employment across the food value chain. Part of the reason is that the kinds of crops grown in North Dakota lend themselves to profitable export (e.g. soybeans and lentils to Asia). But things are changing.

“People are looking at the possibility of putting more fertilizer to use,” says Schill’s research colleague Matt Leiphon as the area’s traditional wheat harvest looms. “Spring wheat still is king, but corn acres have gone through the roof, up by 430 percent in a decade. New hybrids have come along that can handle more northern climates. That means higher profits and higher-yield crops. With that comes demand for a lot more nitrogen. At some point you’re talking a lot of nitrogen that has to go into the ground when you’re getting yields of 150 bushels an acre.”

Total nitrogen fertilizer demand was forecast to rise by more than 7.6 million metric tons worldwide between 2011 and 2015 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, with demand from North and South America comprising 18 percent of that rise. The 2011 report also forecast a 4.6-million-ton deficit in supply in the Americas when compared to anticipated demand.

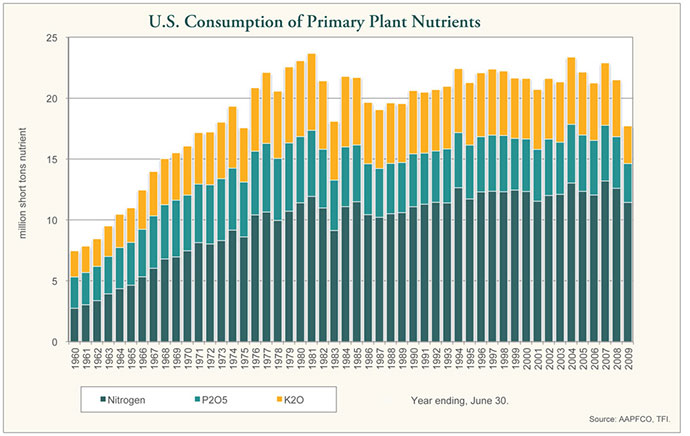

Much of the demand is coming from increased acreage devoted to corn, ever since a 2006 ethanol mandate went into effect. According to The Fertilizer Institute, an organization representing the fertilizer production industry, between 1980 and 2010, U.S. farmers nearly doubled corn production (from 6.64 billion bushels to 12.45 billion bushels) using slightly fewer fertilizer nutrients than were used in 1980. But the overall trend across all types of fertilizer is more, more, more. And that has many onlookers concerned about side effects from runoff’s effects on water quality to insidious economics.

“In 2012 we had a glut of natural gas combined with high anhydrous ammonia prices paid by farmers and a booming corn industry,” wrote Kay McDonald, an independent agricultural researcher out of Boulder, Colo., in a recent column. “This convinced fertilizer industry decision makers that the margin for profit had become wide enough to risk building new plants here in the U.S. At some point in the future we will most likely see, once again, that the cure for high prices… is high prices.

“In the interim, we will work like mad to extract more natural gas through fracking,” she continued. “We will turn that fracked gas into nitrogen fertilizer to grow more corn than we need. We will use that fracked gas to convert that great surplus of corn into ethanol. And, finally, we will burn that ethanol in our cars, which we will use to drive to our grocery stores to pay higher prices for our food.

“This is not,” she concluded, “the best picture of an efficiency model.”

Meanwhile, institutions such as the International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC) in Muscle Shoals, Ala., and The Fertilizer Institute tout the fertilizer sector’s responsibility for feeding a world population projected to reach 9 billion by 2050. “Without dramatic improvements in fertilizer technology and cropping methods, the world could face an unprecedented food crisis within the next 40 years,” says the IFDC.

Strong Connections

The NPN facility and the high-tech farms it will serve will be aiming to demonstrate those dramatic improvements, based on generations of experience and rigorous due diligence.

The Grand Forks area study by Praxis coincided with feasibility analysis conducted by the NPN investors in concert with North Dakota State University. Access to adequate water supplies and competitively priced natural gas are two primary assets of the region, the Praxis study concluded, as well as land, rail, highway, electricity, and labor availability.

While the recent tragic explosion of a fertilizer storage and mixing complex in West, Texas, is on everyone’s mind, observers are quick to point out that the proposed plants will be state-of-the-art production, not storage, facilities.

At the same time, North Dakotans are used to having such products present in their communities, and are prone, says Schill, to balance any “recency bias”-driven safety concerns with such factors as job creation, including 2,000 construction jobs and several convoys’ worth of trucking gigs. Moreover, a win-win aspect of the Grand Forks deal is the proposed plant’s site right next door to the city’s wastewater treatment plant, which will supply greywater to NPN.

“There’s a general sense of being pro-development,” says Schill. “It’s a positive economic development and good middle-class employment for the region” with jobs in the $75,000 to $80,000 range. “A lot of people will generally view it that way first and foremost.”

Klaus Thiessen, president and CEO of the Grand Forks Region Economic Development Corp., says when his team convened an ag business task force almost a year and a half ago, the sector had not been closely examined in decades. He calls it the strongest of the area’s four pillar target sectors (aerospace, life sciences and energy are the others) but one that has “always been taken for granted.”

One of the task force members knew a group of people looking to site a fertilizer operation, says Thiessen. A package was put together and a site visit invitation was extended. When the investors came, he says, all the city and state officials were there in one room to greet them.

“We showed them we had the infrastructure and the support long term to make it happen,” says Thiessen, who says the spinoff economic impact goes beyond transportation and construction to include procurement and site services. The value to the tax base is nothing to sneeze at either. A conservative estimate when the plant pays property tax is $7.5 million a year. And those taxes will be coming from a piece of marginal land next to a sewage lagoon and wastewater pond.

A different kind of proximity is revealed with a glance at the map.

“We are within two and a half hours of 800,000 Canadians,” says Thiessen. “Twenty-five percent of our retail business is from Canada. Some national chains in Grand Forks, on a per-square-foot basis, rank right up there. And on the ag side, there has been cross-border trade and investment for years. Canada is one of North Dakota’s largest export markets, if not the largest. And Winnipeg is the northern terminus of the Red River Valley.”

It’s just one more aspect of an ideal convergence. Or as NPN’s Larry Mackie expressed it at the announcement in May, “I drool over that site. It’s as good as it gets.”

(A previously posted version of this article quoted Praxis analyst Matt Leiphon citing yields of “250 bushels an acre.” The current version reflects the correct figure of 150 bushels per acre.–Ed.)