When Oakridge Global Energy Solutions (OGES) this fall announced its commitment to lithium-ion battery manufacturing in Palm Bay, the southernmost of seven municipalities that comprise Florida’s Space Coast, Florida Gov. Rick Scott named Oakridge Executive Chairman and CEO Steve Barber a Governor’s Business Ambassador, bestowing on Barber a medallion nearly as gaudy as the company’s promise of 1,000 jobs.

Last week concerns arose that both could prove to be empty tokens, as local TV news reporters found that the new operation’s approximately 40 employees had not been paid for over a month. While Barber claimed on camera that battery production was taking place and that the slow paychecks were part of the growing pains of a growing enterprise, the company’s recently deposed CFO said off-camera that no battery production was taking place at all.

It was one of several apparent red flags that sent government officials scrambling over the past week. In an interview with Site Selection, however, OGES President Lee Arrowood says all is not as shaky as it seems, while also highlighting what every company leader knows and feels when embarking on a growth phase: New ventures, by definition, are fraught with peril.

“Startup is not for everyone,” he says. “The whole thing is risky.”

Checklists and Milestones

On the same day Gov. Scott draped the medal around Barber’s neck, the company filed an 8-K form with the SEC that noted the resignation of that CFO, Tami Tharp, just after bringing Karen Jackson into the position of financial controller (a job title that normally reports up to the CFO). Tharp had just signed a contract in July that would have paid her $120,000 a year in salary.

Last Friday, Gov. Scott announced that Jesse Panuccio, executive director of the Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO), was stepping down. DEO is the lead dog in performing due diligence in order to qualify companies for potential performance-based incentives. A $33-million incentive package from the State of Florida, the City of Palm Bay and the Economic Development Corp. of the Space Coast is attached to these 1,000 jobs. However, it appeared the resignation was unrelated to the Oakridge situation, as Panuccio had clashed in the past with the state senate and, according to news reports, was in danger of not being confirmed in the new legislative session.

Terms of the incentives agreement by state law remain confidential until 180 days after the agreement is signed. Contacted this week, however, the agencies involved were quick to point out that their tax abatements and other incentives are all performance-based.

“This company has not received any incentive funding from the State of Florida,” said DEO Press Secretary Morgan McCord in an emailed statement sent in response to a dozen questions from Site Selection. “We are reaching out to them to gather more information. The Florida Department of Economic Opportunity holds companies accountable to all contract requirements in incentive deals. Those requirements include adding jobs, maintaining jobs, wages, and capital investments. The majority of incentives are pay-for-performance to ensure that state taxpayer dollars aren’t spent until all requirements are met.”

“Oakridge is at the beginning stages of introducing a new innovative technology into a competitive industry,” said Lynda Weatherman, president and CEO of the Economic Development Commission of Florida’s Space Coast, in an emailed statement. “Companies at this stage may face challenges which result in unfortunate adjustments. The local incentive the company qualified for is an Ad Valorem Tax exemption (AVT), which is performance-based. Therefore, once Oakridge meets the metrics agreed upon, the company is eligible to receive the tax benefits.”

“They don’t get any tax breaks until they fulfill their promise, so we’re not in jeopardy,” said Andy Anderson, economic development and external affairs director for the City of Palm Bay and a Brevard County commissioner, in a phone interview late last week. “We’ve had a lot of discussions with the company, looked at their 10-Q, and I think they’re going to be okay. I think this is just a hiccup at the beginning. From what I read in the financials, and what they’ve told me, the assets they can liquidate are pretty huge. They made a statement about being a self-financed company by the first quarter.”

Anderson and his team were due to meet with OGES leaders on December 9. But whatever the upshot is, he says with major employers like Northrop Grumman and Harris Corp. locally, and an increasingly diversified industry base statewide, “these things don’t stress us out like they would have eight years ago. And the housing market is rocking right now.” Even if the OGES abatements had to be pulled back, he says, site selectors continue to pay visits to the area, drawn especially to high-bay facilities. “It’s a good problem to have,” he says.

Life on the Edge

Barber, from Australia, was unavailable by phone this week. He claims 30 years of international entrepreneurial activity (including “offshore financing structures and the creation of new ventures”). His resumé is strong on entrepreneurial and international jet-set boilerplate language, but short on naming names in terms of accomplishments in the business world. His bio features a blurry portrait of him on a beach with sunglasses. His wife Suzanna Barber, the company’s VP of corporate communications, is listed on the firm’s leadershp page above the company president Lee Arrowood.

But poor website design is not necessarily indicative of performance, nor of shallow intentions, a conversation with Arrowood reveals.

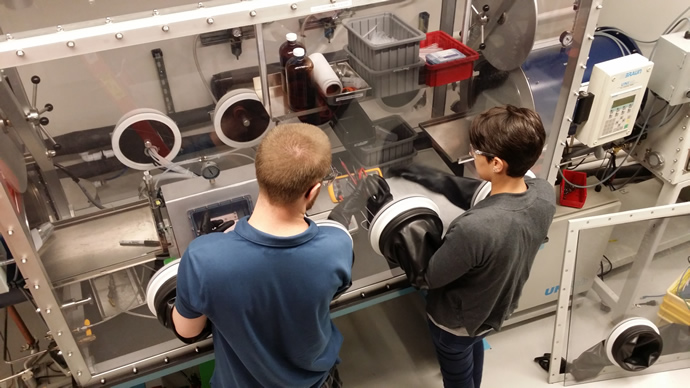

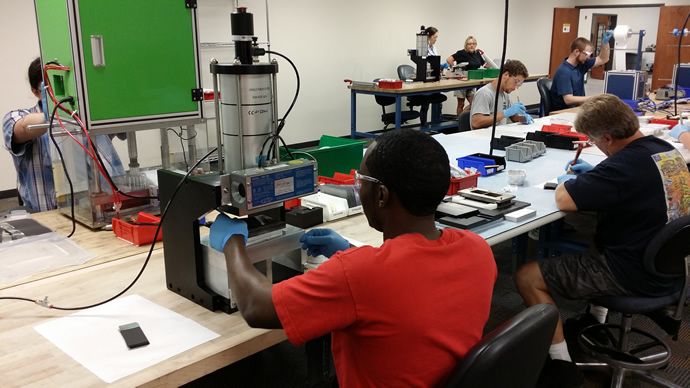

“We have been producing for about three months,” he says, explaining the various types and sizes of cells in the battery business, from prismatic cells in phone and laptops to larger models in golf carts. “For the last several months we have been producing small-format cells, a couple thousand a month, while still working out a few of the bugs. They are now being sold to retailers, by distributors, for the radio-controlled markets — commercial, consumer, government and defense. Anybody that needs a battery for an unmanned radio-controlled vehicle — under water, on the ground or flying in the air — we produce products that they could use.”

Arrowood says OGES has large contracts with two of the largest distributors in North America (which he prefers not to name) and smaller contracts with firms building small drones. Orders are coming in and being filled, and OGES products are hitting shelves, he says. The total number of people on staff is between 35 and 50, he says. The goal for 2015 was to add 15 people with an average pay of $50,700. So far 12 have been added to payroll, at an average salary slightly above that figure.

Arrowood says it hurts to hear the accusations from former employees, especially when he went above and beyond in explaining the nature of risk to potential hires.

“The company has big plans, and with big plans comes risk. It is important EDOs are willing to open their doors to start-up companies working on new innovative technologies.”

“I hired every single person myself,” he says. “All but two were unemployed.” He spent a lot of time making sure that “every single person who comes in understands this is a startup business, not a big pocket of money that will last forever and ever. Every single one looked me in the eye and said ‘I understand.’ Every week I have an all-hands meeting and let them know what the cash situation is, whether it’s really good or things are getting really tight.”

Those tight times occurred several times before he came on board in August 2013, and have occurred four times in the last 18 months, he estimates, varying in length from a couple of days to between two and three weeks. “The current situation is longer than that,” he admits. “But every single person coming in knows what the situation is.”

Arrowood tells employees, “You need to do what’s best for you and your family. Just because I’m all in doesn’t mean everybody else should be.” He offers the option of temporary layoffs so they can draw unemployment until positions can be funded again, or staying on and, when the next round of funds arrives, being made whole. The curious thing, he says, is that “all hands are here. No one wants to take the layoff.”

Things may be about to change for the better. The company’s last payroll was run on October 23. On December 9, all employees were due to be paid in full and made current, says Arrowood, thanks to an influx of money December 7. The pay cycle will even include some holiday bonuses. All along, he says, the company also has routinely given anywhere from 10,000 to 100,000 shares in the company to certain employees.

“Steve Barber is very sympathetic,” he says. “People who stay here and continue to work even though pay’s delayed, he gives shares to — 10,000 shares is like $5,000 with a potential upside.”

Though specifics remain confidential due to the non-disclosure agreement with the state, the company’s plans include phased-in hiring of those 1,000 employees over the next three years, spread across four shifts of about 250 people per shift, running 24/7, plus administrative staff.

“When you invest a lot of money in capital and equipment, you want it running 24/7,” says Arrowood, noting that those planned four shifts could evolve into six.

Landing in the Launch Zone

Lost in all the drama is the original story of how OGES came to be, where it wants to go from here, and why it chose the Space Coast, which since 1999 has brandished the “3-2-1” area code synonymous with its space exploration heritage.

Arrowood says the history goes back to Dr John Bates, who created thin-film solid-state batteries while working at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

“Worldwide, he’s the Babe Ruth or Cy Young of solid-state, thin-film batteries,” says Arrowood, a longtime Little League coach and umpire. Bates formed a company called Oak Ridge Micro Energy, but just as it was on the verge of going into manufacturing, “they realized they were way ahead of the market,” he relates. “In the early 1990s, there were no cellphones, iPods, tablets or smart watches.” The firm ran out of money and momentum, and went mostly dormant.

That changed in 2012, when investors and experts from Melbourne, Fla., and New Jersey got involved. They included Dr. A. J. Manning, another battery industry rock star, semi-retired, who had developed innovative technologies in the commercial lithium battery arena.

“They did 100 percent R&D for about a year, ran out of money, and at that point, the folks from Precept got involved and said they’d pick up the funding from there.”

Oakridge has been around since 1986, primarily as a shell company, until Barber and his Precept Fund Management SPC investment firm swooped in in 2014. A 2013 legal agreement states that Oakridge “is a public company organized under the laws of Colorado, headquartered in Utah, and with operations in Florida.” In mid-September, the company had a market cap of approximately $320 million. Two weeks later, in the latest of a series of announcements and rollouts that included that medal ceremony and Barber’s intention to achieve a listing on NASDAQ, it said its market cap was more like $250 million. At the company’s Nov. 30 third-quarter earnings announcement, it reported assets exceeding $76 million and liabilities of just over $2.75 million.

The firm started looking at manufacturing in summer 2013. Arrowood was brought in as a director of quality, to create metrics and shepherd the transition from R&D to manufacturing. He and the Barbers looked at more than 20 properties in five metro areas in Nevada alone (even as Tesla was doing the same thing for its own gigafactory in the same state). They also looked in Utah, Upstate New York, the DC area, outside Indianapolis and outside Philadelphia.

“I toured so many buildings they all started looking the same,” Arrowood says. Then the search included Florida, where he’s lived since the early 1980s, working for Harris Corp. among others. Orlando, West Palm Beach, Daytona and Tampa were all examined, and like the other areas weighed according to such factors as building and real estate costs, workforce wages and workforce availability. The end result honed in on the building OGES now occupies, originally built in the early 1980s, occupied by a manufacturer of rugged computers for the military, then retrofitted by DRS, which moved out in 2012.

In parallel with the building search, OGES was hot on the trail of major equipment to fill it. Numerous visits and overtures were made with the former International Battery Co., which had operations in Alachua, Fla., and Allentown, Pa. Sold to Bren-Tronics, the company was a respected maker of batteries and battery systems for the military. Arrowood was not willing to pay the first couple prices Brentronics named for the International Battery assets as it tried to vertically integrate the company. Then the company’s founder Leo Brenna passed away in 2014. A closeout price followed shortly thereafter, with the stipulation the building in Allentown be cleared out within six weeks. OGES sent up a crew of eight, and “that’s where a good chunk of our equipment right now came from,” says Arrowood.

Forward Progress

Asked about the background of his primary investors, Arrowood notes that OGES is a public company, so background checks are frequent, with three in the past 18 months.

“I can tell you Mr. Barber’s has come back absolutely spot clean in all three of them,” he says. “I believe in Steve — personally and professionally, he’s tops. He’s a real person, a very open-book kind of person and a good person.”

Arrowood says he’s checked in repeatedly over the past week with all the government agencies, all of whom understand the nature of dealing with disgruntled former employees. That hasn’t made it any easier, but the company is moving forward.

“Honestly, it’s very painful personally, because I know where these folks were when I hired them,” Arrowood says. “There are no secrets. There’s not a floor safe full of thousand-dollar bills I’m hoarding. We’re between funding events … We bent over backwards to do everything we could to prepare people. In my heart, it hurts really bad when people say what bad people we are, when the only reason you’re here is that you wanted to be here.”

As for Barber’s whereabouts, Arrowood says, “Steve is currently securing significant amounts of money, in the millions of dollars, and it will be all the funding we need to finish getting into manufacturing. By mid-January, we’ll be in full production in this facility with at least two shifts, and won’t add a third shift until maybe February.”

The family investment fund Barber oversees includes investors from Japan, Australia and Europe, as well as the US. In October OGES added three new directors, including Australians Vic Psaltis and Theo Lianos, who formed Venture Exchange Pty Limited in Australia in 2000 and have worked through dozens of business continuity plans. Psaltis has worked on corporate deals and finance with several global banks as well as KPMG.

The current product portfolio encompasses batteries for products as diverse as RVs, data centers and that radio-controlled niche, plus a few other areas “we’ve looked at pretty hard, but haven’t announced yet,” says Arrowood. Much of the work on site today involves packaging, so a solution that’s elegant on the inside looks just as elegant on the outside. The ultimate competitor? China.

“We’re taking on Chinese manufacturers head-on,” he says, with a cost-competitive product that may be more expensive than those overseas batteries, but will more than make up for it in quality. “Their cells will typically swell up and cease to function after 10 to 100 charge/discharge cycles. With ours, we’re up to over 500 cycles, and with some large formats, up to 9,000 cycles. We’re doing cycle testing, and we’re looking at markets that have a high energy requirement, like the golf cart.”

Trade shows and events are in the works for 2016, he says.

“Our third-quarter results reflect the significant investment that Precept has made into this exciting business,” said Barber in a November 30 earnings release. “From development of products to purchase of manufacturing equipment, this business is now fully operational and poised for growth.”

“During the process of restructuring this business we had the opportunity to purchase a major supply of equipment and have continued to develop IP [intellectual property] in the battery space,” said Barber. “We are very pleased with the third-quarter results and expect the fourth-quarter results to be even better. Our business plan is simple; we develop, manufacture and sell products. I know it’s a bit old-fashioned, but we are in the business of manufacturing.”

Over the course of the next 18 months, says the company, it will ramp up and install more than 2.6 gigawatt-hours of production capacity of electrodes, cells, and batteries, using equipment housed in over 350,000 sq. ft. of new manufacturing space.

“We have completed the restructure, have taken the brakes off, and are moving ahead full speed,” said Barber. “We are very pleased with the new corporate facility. The city of Palm Bay, Florida, has made us feel very welcome and we look forward to a very good long-term relationship.”

That’s the kind of relationship leaders like Lynda Weatherman of the Space Coast EDC can get behind, all with an understanding of where business risk takers are coming from.

“The company has big plans, and with big plans comes risk,” she says in an email. “It is important EDOs are willing to open their doors to start-up companies working on new innovative technologies — because those who do succeed generally bring large investment into their community.

“Economic developers deal with companies across a spectrum of maturity and financial stages,” she says. “”Brevard County is successful because we welcome companies with big plans.”