This story continues Site Selection’s series on trade agreements that began with a three-part analysis of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) in Trading Up, Let’s Be Clear and Looking Out for the Little Guys.

The conclusion of negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) by 12 participating countries on 5 October 2015 has been heralded as a landmark event in the trade arena — another small step in the journey toward truly global free trade. The TPP impacts one-third of global trade and encompasses 40 percent (US$28 trillion) of the global economy. While some of the agreement’s economic impact will be the result of improved competitiveness of existing investors in each of the signatory countries, a significant portion of this impact will be the result of increased investment in these countries as companies seek to take advantage of the improved market access the TPP provides.

Market access is the factor most often cited by companies as influencing their investment location and market entry decisions. The lower tariffs and reduced barriers to FDI afforded by the terms of the agreement are already having a significant impact on the foreign direct investment (FDI) and location strategy decisions of numerous companies as they consider expanding existing capacity or investing in greenfield operations.

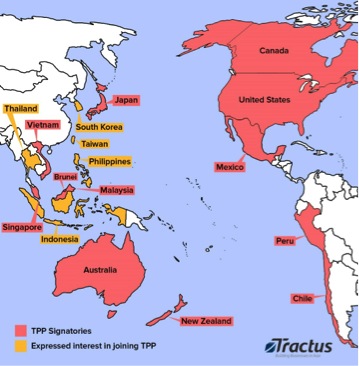

While an uphill battle for ratification remains, particularly in the US, investors already seem to have discounted the possibility of failure. We are seeing not only tremendous interest in investing in TPP signatory countries, but also the diversion of interest from neighboring countries that are not signatories, such as Cambodia and Thailand, toward Vietnam, particularly in the textile industry.

Toward 21st Century Trade

Though the TPP is often thought of as an international trade agreement, it is, in fact, a comprehensive commercial agreement that goes beyond the typical concept of trade in goods. The agreement’s scope reflects the fundamentally different nature of trade that has developed in the 21st century.

In the early 20th century, international trade was largely limited to the movement of raw materials from one country to another for the production of final goods. Later, tariff barriers forced companies to locate production in their most important markets, whether or not it made economic sense. Tariff-driven location decisions became less prevalent as tariffs started to fall (first negotiated through the GATT and then the WTO) coupled with the advent of low cost computing, mobile telecommunications, and the Internet. Collectively this allowed for the unbundling of the manufacturing value chain, creating the modern global supply chains that we are all familiar with.

The hallmark of modern global supply chains is that they encompass the movement of skills, technologies and intermediate-stage production components by means of investment in factories, R&D centers, training facilities and ICT services in locations dictated more by true comparative advantage than distorting tariffs. As tariffs on goods and barriers to trade in services fall further, companies can adjust their location strategies to take advantage of better market access, lower costs and access to talent.

Going Beyond Trade

The increasing complexity of international trade — which is in fact a trade and investment ecosystem — requires a more complex and multifaceted approach to trade agreements.

Consequently, the TPP goes beyond eliminating or reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers across trade in goods and services, and also includes measures to liberalize investment, promote cooperation among major telecommunications services providers, improve IP protection, increase the transparency of regulatory regimes and dispute settlements, ensure that SMEs can take advantage of new regulations, and set standards for labor and environmental protection.

The agreement touches upon many of the key factors companies consider when making an investment location decision. Consequently the TPP will significantly impact not only trade but also investment in the region, as evidenced by A.T. Kearney’s 2014 FDI confidence study, which reported that 54 percent of business leaders surveyed said the TPP, if implemented, would impact their investment location decisions.

There Will Be Winners

Vietnam stands to gain the most from the TPP, with exports projected to increase by 28.4 percent over the expected baseline in 2025 without the TPP. Apparel and footwear, two of the most important sectors in Vietnam’s economy, could see exports increase 45.9 percent over the expected baseline in 2025.

Vietnam exported nearly US$7 billion worth of apparel to the US in 2012, accounting for 34 percent of US apparel imports, and this enormous market could expand even further under the TPP. The TPP has a “yarn forward” rule for textiles, which requires any member country that exports textiles to other TPP countries to use yarn that is either produced locally or in other TPP countries. Until now, Vietnam has sourced about 88 percent of its textiles from China and South Korea, so Vietnam has to significantly alter its textile supply chain in order to enjoy the TPP benefits. The yarn forward rule has already impacted FDI in Vietnam, with two large Japanese manufacturers making investments in dyeing and materials production facilities.

For American textile manufacturers, the yarn forward rule not only creates export opportunities for textiles to Vietnam, but also enhances FDI opportunities for textile manufacturing in Vietnam. From 2013-2015, more than U$3 billion of FDI flowed into Vietnam from companies in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and Australia to manufacture textiles, apparel, and footwear, expecting to take advantage of TPP rates.

Vietnam is not expected to see additional significant growth in its top exported commodities, such as coffee, rubber, cashews, and pepper, as current preferential trade agreements between Vietnam and TPP countries already provide low or duty-free rates. However, smaller export sectors such as cassava starch, processed foods and honey could gain. Overall, Vietnam’s GDP is expected to be 10.5 percent higher than the baseline in 2025 without the TPP.

There Will Be Losers Too

If the TPP comes into force, it will have a negative impact on China’s economy. The Brookings Institution estimated China’s losses to be similar in magnitude to Vietnam’s gains, as trade, and the investment that produces it, is diverted from China to other TPP countries. By 2025, these losses may be up to US$46 billion.

These losses could be turned to gains, should China decide to join the TPP. It is estimated that the gains to China could be over US$800 billion by 2025, should they (along with South Korea, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand) join the TPP. Gains for the US would be US$330 billion under this scenario, five times the forecast with the current TPP countries.

This economic upside provides significant incentive for China to participate in the TPP. However, China faces numerous hurdles should it wish to join, as doing so would require reforms impacting areas such as the role of state-owned enterprises and access to the Internet. It is likely that the TPP will propel China forward on reforms in these areas. We expect China to take a “wait and see” approach, watching the ratification process in TPP countries and waiting to see which other countries in the region will join.

More Partners Expected to Join Soon

It is highly likely that other countries also will join the TPP as they observe ratification in TPP countries. South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, and Taiwan have already expressed interest in joining, and on October 26th, President Joko Widodo of Indonesia announced during a visit to the White House that Indonesia plans to join the partnership. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen is vocal about his desire for Cambodia to join the TPP. Exclusion from the TPP would likely result in a significant amount of trade and manufacturing investment being diverted from Cambodia to Vietnam, an unwelcome drag on an economy that has already seen trade with the US slowing down.

Should China, South Korea, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand choose to join the TPP, gains for the US would be $330 billion — five times the forecast with the current TPP countries.

The US welcomes additional signatories to the TPP, as US Ambassador-designate to Thailand Glyn Davies recently remarked at an event hosted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Thailand, “The TPP is a high standard, ambitious, comprehensive and balanced agreement that sets a new standard for global trade … If Thailand or others want to explore joining TPP — and we note that there is a bit of a live debate about that here in Thailand at the moment — the United States and our 11 TPP partners would very much welcome that.”

Putting Pressure on the RCEP

The conclusion of TPP negotiations undoubtedly puts pressure on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) nations to accelerate their discussions, begun in 2012. The RCEP includes the 10 ASEAN nations (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) as well as Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand. The RCEP is effectively led by China, the largest economy in the partnership. The potential RCEP agreement, which some consider an alternative to the TPP, is widely perceived to pit US economic leadership in the region against that of China.

The extent to which the RCEP will impact investment location decisions is highly dependent on the specifics of the agreement, for which there is currently very little clarity. While the TPP sets a high bar for regulatory transparency, IPR protection, rule-of-law and dispute resolution, all of which are important investment and location decision-making factors, it is very likely the RCEP will not emphasize these trade-related investment measures, muting its impact on location decisions.

Divergent interests within ASEAN, as well as security concerns brought about by territorial disputes in the East China and South China seas, have strained relations between many of the key participants and China. Additionally, the inclusion of India and Indonesia, countries that perennially lack enthusiasm for trade liberalization, will delay the progress on the accord further.

Finally, a number of RCEP nations, including South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Cambodia, have already expressed interest in joining the TPP. All of these factors will make it very challenging for the RCEP nations to develop an agreement as comprehensive as the TPP in the foreseeable future, and there will be little consideration given to the agreement in firms’ investment location decisions.

Path to Ratification

There is still a lengthy process of ratification in each of the 12 TPP countries before the agreement comes into force, and a number of countries face an uphill battle. Malaysia is preoccupied by scandal as Prime Minister Najib Razak faces corruption charges, and both the US and Japan will also face difficulties ratifying the treaty. Vietnam, with substantial economic gain at stake, will likely have an easier time with ratification, as will Singapore, which already has free trade agreements with many of the TPP countries. Brunei will have the simplest ratification process, as the Sultan can sign the treaty into law unilaterally.

The TPP comes into force 60 days after the 12th country ratifies the treaty. In the event that two years have elapsed and not all 12 original signatories have ratified it, at least six signatories, representing 85 percent of the total GDP of the 12 TPP countries, must have ratified it in order for it to come into force.

Because the US accounts for 62 percent of the total GDP of the TPP countries and Japan accounts for 17 percent, it is impossible for the TPP to come into force if either the US or Japan fails to ratify it. The latest that the TPP will come into force, should one of the 12 countries fail to ratify it (not including Japan or the US), is December 2017. As the fate of the TPP is directly linked to the politics of the US and Japan, investors will surely keep an eye on these countries when making investment decisions.

As other members join, the economic calculus of where to locate in Asia will take another turn on the long road to global free trade.

Dennis J Meseroll is a co-founder and executive director and Reuben Shorser is a research analyst with Tractus Asia Limited, a leading FDI advisory and site location strategy firm in Asia. The authors can be contacted at dennis.meseroll@tractus-asia.com and reuben.shorser@tractus-asia.com.

Looking for further insights into FDI and trade? Check out the monthly FDI Report from the Global FDI Association, the recently published report The World’s Most Competitive Cities 2015 and the upcoming WORLD Forum for Foreign Direct Investment in San Diego.