Last July the Washington, D.C.-based watchdog organization Good Jobs First came to Cleveland to issue a scathing report entitled “Paid to Sprawl” that found 164 companies were given property tax breaks for relocating within the Cleveland and Cincinnati metro areas, usually at the expense of downtown. The study called for remedies such as regional anti-poaching protocols and revenue-sharing, and withholding of incentives if projects were not accessible by public transportation.

But the state’s vibrant metro areas are producing more than their share of downtown remakes and re-visions, as it were. Funded by a range of public-private entities, TIF arrangements and yes, incentives, these projects’ campus-style atmospheres often have direct ties to university campuses themselves. And they’re offering corporations seeking infill locations as part of their sustainability goals quite literal new avenues to the talent they covet.

In Cleveland, the newest hip hub is called Intesa (Italian for “agreement” or “understanding”), a US$110-million office, apartment and technology project to be located near the campus of Case Western Reserve University. Led by University Circle Inc. (UCI), developer The Coral Co. and Panzica Construction, the project aims to feature space for start-ups on a second floor that “ribbons” through several buildings, and 110,000 sq. ft. (10,219 sq. m.) of more broadly defined office space throughout the upper stories of one of the buildings.

Peter Rubin, principal of The Coral Co., says the project team has begun to source public financing. Assuming New Markets Tax Credits are reauthorized by Congress, he says, the project will pursue an equity transaction in the range of $20 million to $30 million. Other funds may come from the federal EB-5 program, and TIF. The team has a year to line up and lock down financing, says Rubin, as they work toward a groundbreaking by the second or third quarter of 2013. As the site is evaluated, he says, “a lot of infrastructure improvements have to be made. So far all of our requests for participation on those costs have been well received.”

The complex will feature a 700-car parking garage (1,300 parking spaces overall) and an intermodal transit hub for passengers using a new Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority rapid train station set to debut in 2013. It would also feature extremely high-speed broadband service. Tony Panzica, president of Panzica Construction, calls this aspect of the project “revolutionary.”

Intesa represents the first significant office project in University Circle. “We believe there will be demand from people interested in being close to the educational institutions as well as the hospitals,” says Panzica. The Intesa team is aiming for LEED-Gold certification, an aspiration helped from the outset by the infill location and the adjacency to rail transit.

Mega-Connected

Development of under-utilized real estate is a primary part of UCI’s mission, and the nonprofit is looking at similar development prospects for six smaller sites it owns in the neighborhood.

The project aligns with the university’s leadership in the Gig.U movement, a national coalition of 29 universities with gigabit broadband who want to share it with their communities. Lev Gonick is Case Western’s chief information officer and vice president for IT services, and a nationally recognized advocate for the power of broadband deployment in transforming economies. He says Intesa will be the only commercial property in the region being serviced by broadband infrastructure that’s 300 to 400 times as fast as the typical offering. As part of Gig.U., the campus already is providing gigabit service to some households and a senior residential facility. He says the Intesa broadband play has three aspects.

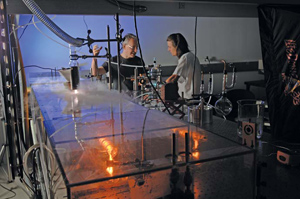

“The initial concept was to afford access to huge broadband through the building and the tech ribbon in order to showcase technology,” he says. “These are top-tier, FORTUNE 100 tech companies working on next-generation projects. Big broadband is a given, and they can only demonstrate that in a lab.”

Today such a process might involve having to demonstrate the technology at the various labs of different business partners. Intesa aims to be the one-stop shop for advanced demonstration services.

The second pitch for gigabit broadband? Gamers, digital media pros and the “two guys in a garage” types of entrepreneurs, says Gonick, citing Case Western alumni and tech pioneers Craig Newmark (Craig’s List) and Paul Buchheit (Google Employee No. 23 and the creator of Gmail). Gonick says he’s constantly working with these kinds of idea people, but often “I’m incubating their new ideas deep in the bowels of the university where nobody can find them,” he says. Intesa offers the promise of a place to be comfortable as a startup, and to experience “all the gelling that goes on,” says Gonick. It’s not a revenue generator, but it’s an important piece of the culture.

Last but not least comes the array of tech companies located from Detroit to Pittsburgh who want a local base from which to reach out to major customers in the UC neighborhood such as the school itself, University Hospital and Cleveland Clinic. Other potential directions include attraction of financial services/shared services (Quicken recently has relocated back downtown), as well as the possibility of data center activity, despite the relatively high rents of the neighborhood.

Rubin says the project’s timing is lucky, with new hotels and the new rail station coming.

“You can’t underestimate the power of being adjacent to a brand new rapid transit station,” he says, noting companies now are hiring a demographic who may not want a car. “We have that chance to say, ‘Live, work, and dine here, see a movie every night, and take rapid transit downtown, to the airport or to every sports facility in Cleveland. Regardless of what we do, the road map is already set for our project to become the nexus of technology, art and business.”

Metro Mixed-Use Matrix

Other progressive “mixed-reuse” is going on near the Cleveland State University campus, where Polaris Real Estate Equities and Buckingham Companies are developing the $50-million Campus Village. And in the Flats East Bank waterfront area where Lake Erie meets the Cuyahoga River, a once-christened entertainment district is being born again with a new hotel, an 18-story office building (with Ernst & Young as the primary tenant) and four restaurants, including country star Toby Keith’s I Love This Bar & Grill. Wolstein Group and Fairmount Properties are the lead developers of the overall area project, which announced its second phase in March.

The Toby Keith concept already has opened at Cincinnati’s groundbreaking riverfront redevelopment area known as The Banks. Since a master plan approval in 1997, local and federal governments have invested over $2 billion in the redevelopment of Cincinnati’s Central Riverfront, formerly a freight rail hub. Set among the gargantuan new stadiums along the river, the live-work-play concept of The Banks will be one of the final pieces set in place, including an office building slated to rise during its later phase.

Among other redevelopment highlights in cities across Ohio:

University Park Alliance (UPA) is leading the implementation of Akron’s core city master plan centered on the redevelopment and revitalization of University Park, the 50-block urban neighborhood surrounding The University of Akron. UPA announced last October the signing of a master services agreement with internationally recognized real estate developer KUD International LLC. In February UPA released the findings of two parallel reports showing substantial economic impact from the core redevelopment plan by 2030, even with very conservative growth assumptions. Among the findings: UPA’s planned initial retail, office and hotel developments by 2016 will annually contribute $183 million of economic activity, 1,400 jobs and $9 million of tax revenue for University Park.

In April UPA signed a partnership agreement with Equity Inc. (Equity), an Ohio real estate services firm, to build and manage the first two buildings of a planned “Market Square” mixed-use development, located in part of the area’s Crossroads District that has been designated by the City of Akron as its “Biomedical Corridor,” targeted for technology and innovation development.

Columbus2020 tracks economic development project announcements made by public and private sector partners in the 11-county Columbus Region. In 2011, 143 total projects were announced in the region, 43 percent of which were in the manufacturing sector and 26 percent of which were in headquarters/office functions. The projects represent a combined total of nearly 20,000 jobs anticipated to be created or retained. Some downtown restoration may soon do its part.

This spring, a $50-million residential/retail complex was announced for Columbus Commons. In addition, Mayor Michael Coleman announced the city’s backing of two major projects: the $36-million Scioto Greenways plan calling for removal of a dam in the Scioto River and creation of 33 acres (13.4 hectares) of new downtown greenspace for such uses as boating and biking; and the mixed-use redevelopment of the 56-acre (22.7-hectare) Scioto Peninsula. Coleman hopes to see the Greenways plan completed near the end of 2015. The project will be led by the Columbus Downtown Development Corp.

“I am excited by the prospects for the Scioto downtown, and with the support of our partners in the public and private sector, not only will we improve our natural environment, but the business environment as well,” said Columbus City Council President Andrew J. Ginther.

A similar dam removal and restoration project, River Run, is raising funds now in downtown Dayton and hoping to reach its goal of $4 million this year. And a 167-acre (68-hectare) mixed-use development called “The Heights” was approved last August for Huber Heights in the northern part of the Dayton MSA, in an area called the “Crossroads of America” because of its I-70/I-75 interchange. City officials, who have agreed to $223 million in TIF funds, project the complex — including 400,000 sq. ft. (37,160 sq. m.) of office space — will create 1,900 permanent jobs at full build-out.

A different brand of redevelopment is under way in the southern Ohio city of Piketon, where Ohio University’s PORTSfuture project has engaged hundreds of community members from Pike, Jackson, Ross, and Scioto counties in developing possible future use scenarios for the former Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant (PORTS) facility, which in 2001 ceased uranium enrichment operation and was placed in “cold standby” status, then shifted to “cold shutdown” in 2005. A report was submitted in early March to the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Environmental Management for their consideration as they make clean-up and risk reduction decisions about the site. February 2012 statistics showed Pike County had the highest unemployment rate in the state at 15.7 percent.

According to the report, a volunteer advisory group ranked the scenarios from the most preferred to the least preferred as follows: 1) Industrial Park, 2) Green Energy Production, 3) Multi-Use Southern Ohio Center, 4) National Research and Development, 5) Training and Education, 6) Greenbelt, 7) Warehousing, Transportation and Distribution Hub, 8) Nuclear Power Plant, and 9) Metals Recovery .

Northwest Ohio Finds

Its Range: The World

On the topside of the state, there’s a region where the range of corporate interest runs from rural agribusiness to automotive heritage to downtown redevelopment and maritime commerce. But it’s all threaded together by sophistication. And that’s attracting interest from companies around the world.

The Toledo MSA saw manufacturing job growth of 3.9 percent in 2009-2010 after losing 38 percent of manufacturing jobs between 2007 and 2009, said Dr. Michael Carroll, director of the Center for Regional Development at Bowling Green State University, at the center’s annual State of the Region conference in April.

He also pointed out that warn notices, required by the state from companies approaching significant layoff events, were only union-related in under a fifth of cases. One of the area’s strengths through the recession, he said, was its rural component, sporting agribusiness combined with significant manufacturing and a lack of loan speculation.

Jonathan Gemmen of Austin Consulting, who works on the CSX Select Site program, noted strong area assets such as that very railroad’s Northwest Ohio Intermodal Terminal in North Baltimore; the Port of Toledo; the Regional Growth Partnership; and the history of partnering by Owens Community College and by BGSU. Like others, he also said the new right-to-work law in Indiana could cause some concern for Western Ohio in regional site selection competitions. At the same time, however, buoyed by activity at First Solar, the University of Toledo and other employers, the region has a viable renewable energy sector.

“Do you know how many areas would love to have a research niche in anything?” he asked his audience. “You have that here in Toledo.” Even with tainted government involvement, a dip in subsidies and an uncertain future, he said, “that research will continue to take place here,” in the shadow of significant corporate headquarters and a strong manufacturing tradition.

Sites of interest, he said, include Eastwood Commerce Center in Wood County, named a CSX Select Site in part because a major natural gas line runs right under it, and it’s next to one of First Energy’s biggest substations.

Another site worth attention, he said, is the Ironville site along the Maumee River at the Port of Toledo, a former Chevron property that boasts sites of 80 and 100 acres (32 and 41 hectares), with a new port-run intermodal rail service that connects to both Norfolk Southern and CSX. Plans call for three phases of development focused on using the waterfront acreage for material delivery and handling to support a new manufacturing base located on the balance of the property. The Port Authority purchased the former Chevron property for $3.4 million in 2008, then formed a private-public partnership with Midwest Terminals of Toledo through a long-term lease for the property. The land was used as an oil refinery from 1890 to 1987.

“It’s ugly, but it has Great Lakes water access and two Class I railroads,” said Gemmen. “There are not too many of these left in the country.” He said freight consultant John Vickerman likes the Ironville site “because you have 40 acres [16 hectares] to play with, and you can really create something that’s very flexible.” The shift in ports going forward is the omniport concept, he said, defined by their sheer flexibility.

History Comes Alive

The Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority features some of the best vantage points in Toledo on its property. It also may have the optimum vantage point on the city’s future.

Downtown, the Triple-A Mudhens baseball stadium and Huntington Arena continue to fill up, as do the latest red-brick condo redevelopments. Across the Maumee River on port property, Chinese concern Dashing Pacific is behind the high-end residential and retail redevelopment of the marina district, building on an already thriving restaurant cluster and looking to create a destination full of flowing water features and picturesque venues. Chinese investors of both the individual and industrial variety continue to show great interest in downtown Toledo and the greater metro area.

The port district’s transformation is perhaps best captured by the planned April demolition of the longstanding Toledo Edison power plant, whose stacks long symbolized Toledo’s industrial might. But that industrial character still lingers as more than a ghostly presence.

The Kraft Nabisco flour mill on Port Authority land is one of the largest in the world, and makes the flour used in every Nabisco product sold in the United States. A drive around the port reveals the longtime yard of American Shipbuilding, two large fabrication buildings belonging to Heidtman Steel (now available for development), the Ironville area with its new locomotive, and U.S. Foreign Trade Zone No. 7, which includes what’s commonly referred to as “Coal Mountain”: 400,000 tons of petroleum coke purchased from Superior Energy and owned by Ontario Hydro. Ontario is moving quickly away from coal by 2013, so the pet coke is likely bound for another buyer eventually. Chinese concerns again may top the list, as they continue to seek coal (as well as iron ore) worldwide to keep up with their country’s insatiable demand.

The FTZ comprises 125 acres (51 hctares) with 750,000 sq. ft. (69,675 sq. m.) of indoor storage. Commodities found on the grounds include various metal ingots and billets. “It’s a great laydown area for large cargo,” says Paul C. LaMarre III, manager of maritime affairs, Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority, and executive director, S.S. Col James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. He notes the port’s recent usefulness to wind energy equipment transporters.

Getting Into the Site Business

When a lack of site inventory was evident in the region, proactive property development became a stronger part of the Authority’s mission in 2005, says Matt Sapara, VP of operations and development and COO. The Authority now owns approximately 850 acres (344 hectares), with seven linear miles (11 km.) of coastline, large parcels and rail. “The leads we’re beginning to get are incredible,” he says, noting the receipt of a letter of intent that very morning.

The Authority was sent into a tailspin in summer 2011 when BAX Global, a global cargo service provider at the Toledo Express Airport, announced it was closing and having to let go more than 300 people. But, says Sapara, “The local team decided they had the acumen to run a similar operation but run it more on trucks than planes. It sat dark for three weeks, then was up and operating.” By December, BX Solutions was employing more than Bax had, with 452 on the payroll. Sapara says the energy from that rebirth provides new momentum to the 175 acres ready for development near the facility. “It’s really breathed new life into the entire airport in terms of cargo development.”

Asked about the business arrangement, Sapara says the Port looks to be a partner first and foremost: “It would have been so easy to saddle BX with a large rent up front, but we had flexibility with them because we knew the opportunity that existed,” he says. “As they grow, we share in that.”

The port’s goal is site inventory development, combined with financing tools such as SBA loans and the Northwest Ohio Bond Fund. The Authority has lent more than $2 billion since 1988 with no defaults. “Our bond fund is set up to take more risk sometimes, as long as the payback is there,” says Sapara.

But even with the industrial brownfield opportunities available in such a Midwest crossroads location, he says, the private sector has not quite stepped up as the recession fades, and the challenge is further complicated by the fact that traditional funding sources in Ohio will have a different face next year, with some being cut. It’s a frustration, especially when such infill sites can counteract sprawl and greenfield development while also helping companies meet sustainability goals.

LaMarre says the working port continues to be No. 2 in tonnage on the Great Lakes (behind Duluth, Minn.), moving primarily grain, cement, coal and steel just as it has for 100 years. Like most ports, dredging is its No. 1 challenge, he says, noting a meeting taking place a few floors down on that very topic as he speaks.

Due to runoff from farms, the dredging of the Maumee River’s sedimentation represents one-third of the entire Great Lakes dredging budget. The port receives Corps of Engineers funds to remove 800,000 cubic yards annually, “but we silt in 1.2 million cubic yards annually,” says LaMarre. As federal policy regarding distribution of nearly $7 billion in harbor maintenance funds gets ironed out, the Authority is looking at alternative uses of dredge material, including habitat restoration islands and a new type of growth medium.

“We are the first to mix dredgings with sewage to create a product called new soil,” says LaMarre. “After one year of exposure to sun it become Class A topsoil.”

Ready for More

The rural part of Northwest Ohio knows its topsoil. But sprinkled amongst the fields and long straight county roads are some major crops of industry.

The Village of Leipsic, Ohio, in Putnam County, has attracted facility expansions from three major companies in the past 15 years. Pro Tec Coating, a joint venture between U.S. Steel and Kobe Steel, has invested $800 million in special coated steel operations and will employ 350 when its latest growth phase is complete. P&G/IAMS employs more than 250, has invested $175 million in dry pet food manufacturing and is considering another expansion. And POET has invested $110 million in an ethanol plant.

All are located in the same industrial area off County Road 5, and near a large parcel of land called Iron Highway Industrial Park the community is now marketing as a triple-rail-served megasite with 420 acres (170 hectares) under option or at least open to negotiation.

Martin Kuhlman, director of the Putnam County Community Improvement Corp., says there are approximately 40 landowners, and current options in place are based on a starting point of $15,000 per acre, then a percentage of the going rate, along with a pledge of 175 percent of licensed appraised value for home sites. And he says the overall area potentially open for further development could stretch to as large as 7,000 acres (2,833 hectares). The park lies within an Enterprise Zone.

The area is served by major water, electric and gas infrastructure with some redundancy. The first phase of a 140-turbine wind farm is about to be erected, and could one day feed into the backside of the meter. Finally, the area is also served by a unique semi-circle of short-line community railroad that “connects” — in a most barricade-like manner — the Class I services of Norfolk Southern, CSX and the Indiana & Ohio Railroad to one potentially very sweet and very large spot. A 2010 grant awarded to the site by the state requires that it achieve shovel-ready certification. The certification process is administered by Austin Consulting.

Asked if the site has been marketed to the global automotive sector, Kuhlman says there may be some interest from Chinese investors.

Mark Borer, general manager of the POET plant, says rail distribution is a big part of his facility’s location advantage for both inbound and outbound. Being on the eastern edge of the corn belt means paying a bit more for corn, he says, but instead of sending ethanol made out West to Ohio for blending like so many producers have done in the past, his operation is already in blending territory, saving a bundle on product distribution costs.

An additional advantage of the triple-rail setup, he says, is how it’s allowed the company to branch out from traditional east-west or north-south rail alignments that therefore have built-in costs related to a change in axis. Instead, the company can affordably reach out to, for example, poultry plants in the Southeast with its distillers dried grains (DDG) feed by-products.

Borer says the region’s work force does its own blending, combining a farm country work ethic with an automotive industry legacy that means they’ve had strong exposure to advanced tools. And the Putnam County team is proactive: “When they see opportunities for us to benefit from programs, they call us.”

Finding Findlay

A short drive down the road from Leipsic, next to I-75, sits the City of Findlay. Tony Iriti, economic development director, Findlay-Hancock County Economic Development, served as mayor of Findlay for four years, was city auditor before that, and led a task force that developed a flood management solution with the Army Corps of Engineers after a 100-year flood struck in 2007. So it’s fair to say he knows every square inch of town, and all the stories that lie underneath.

The city is known for its ability to work with industry, establishing a reputation for its plethora of non-union shops as well as its speed and flexibility. But even in a city as conservative as Findlay, says Iriti, residents voted in two levies in Nov. 2009 to pay for additional flood control and police protection, as well as a third $75-million measure to back the construction of two new middle schools and a vocational tech school, now nearing completion adjacent to Findlay High School.

Hamlet Protein, a Danish company that turns soy meal into a food supplement for small animals, has taken space in a showcase building that was built but never occupied by Akron-based plastics coloring company A. Shulman, choosing Findlay over a site in Indiana. Another lead, from German firm Mitec, came through the German-American Chamber of Commerce’s site selection shop in Houston and was interested in the same building.

A local real estate service provider said whoever delivered a check first would close the deal. Once Iriti knew the Danish company was the winner, he did what anybody who knows everyone would do: Knock on doors. He found a company on the other side of the park with a building.

“They talked, and Mitec ended up buying the building,” says Iriti.

Not far away, Whirlpool makes all of its dishwashers, employing 2,200. In Foreign Trade Zone No. 151 just down the road site Tall Timbers Industrial Park, which got started in the mid-1980s and just sold its last lot in 2011. Among the tenants: Bridgestone (which recently relocated some staff from Upper Sandusky); Sanoh America; Whirlpool supplier Createc Corp.; and Nissin Brake Ohio, a supplier to Honda and Toyota. Nissin bought an adjacent building in 2011 and had hired 235 new people as of January 2012. Iriti says his agency worked with RGP to aid Nissin.

“After the earthquake and tsunami, they were looking at bringing things over here,” he says. “When we visited them in Japan, they mentioned parts they wished they could source here, and actually gave me a plastic bag of parts.”

Another Japanese supplier is GSW, which makes wire harnesses for Honda. GSW’s president demonstrated his gratitude to the city by giving it a restaurant, “Japan West,” located in the heart of Findlay’s very alive Main Street.

FORTUNE 50 Spinoff Stays

Adjacent to that street is the yellow-brick world headquarters of Marathon Petroleum Co., which spun off from Houston-based Marathon Oil last year. But there’s nothing new about the company’s presence in Findlay, where it’s been for 110 years.

Angelia Graves, director of public and state government affairs for Marathon, says the company has between 1,600 and 1,700 employees working in Findlay now, running everything from investor relations to refineries, terminals and pipelines. “We may be running the pipeline system in Alaska from the seventh floor,” she says.

She says as the spinoff occurred last year, other sites were examined due in part to the difficulties sometimes encountered in travel from Findlay, some 40 minutes from Toledo, which is in turn another 45 minutes from Detroit’s airport.

“The main disadvantage to Findlay is driving to Detroit, Cleveland or Columbus to get on a plane, unless you’re in the corporate plane just down the street,” she says. “But we’re used to it.”

But access to good employees was a strong factor, she says, and nearly $80 million in tax credits from the state, contingent on certain investments within the next five years, helped too. Moreover, the critical mass of corporate infrastructure already located in Findlay was a tall order to pick up and move. So, “by adding just a few functions, we were able to continue the current operations here,” she says. Besides, she adds, “it was a natural fit to remain located here.”

But the company’s been successful enough attracting talent to town that they don’t fit in the main building anymore. Marathon has moved some staff to two off-site locations in town, as it has added 100 more employees since last year’s spinoff. It’s also invested in other locations in Ohio, such as Bluffton, for backup IT and system servers.

Marathon had its own flood issues in 2007, when water came pouring in the building’s main doors, shutting down the offices for more than a week and causing pipeline operations staff to be taken elsewhere by boat. As a consequence, the company spent several million dollars to get its electrical equipment out of the basement.

“Things like that make you consider whether you keep a FORTUNE 50 company in a city like this, but the city has been very active in getting this addressed,” says Graves.

While the state’s tax changes have been good in some respects for the business community, she says as employees near retirement age, many wish to move to Texas for a few years first, because of Ohio’s personal income tax. She also worries about the company having plenty of access to college graduates: “We’re looking for engineers, accountants … quite a few technical degrees,” she says.

Graves says she was amazed when she arrived in Findlay 14 years ago at the amount of industry and high-paying jobs in a city of Findlay’s size. Tony Iriti adds that the size helps in business attraction too, noting an instance when he was able to call Marathon CEO Gary Heminger (a member of the new JobsOhio board) and ask Marathon to host “lunch for 40 of our closest friends, so they can talk to other business leaders rather than listening to politicians or listening to me,” he says. Heminger and many others in the company are either Findlay natives or have longstanding ties to the community.

It’s the new ties that now beckon to Iriti and others as Findlay’s next great challenge.

Iriti says Findlay has always had a great family atmosphere, but now that companies such as Marathon are bringing in more of the 25-to-35-year-old talent, the city is bringing in brownstones instead of three-bedroom ranches. The retail upgrade is coming too.

“I’ve taken that as a personal challenge,” says Iriti.