This commentary is published by special arrangement with Timothy J. Bartik, senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. It draws on his continuing work and builds on many years of objective analysis of incentives programs and policies that were most recently featured in his 2019 book “Making Sense of Incentives: Taming Business Incentives to Promote Prosperity.”

Bartik’s research focuses on how broad-based prosperity can be advanced through better local labor market policies. His 1991 book “Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies?” is widely cited as an influential review of the evidence on how local policies affect economic development. His more recent work includes developing a database of U.S. economic development incentive programs, studying policies promoting local skills and their effects on prosperity, and examining how early childhood programs could promote local economic development, explored in his 2011 book “Investing in Kids.” Bartik has also done extensive research with colleagues on the effects of the Kalamazoo Promise, a pioneering place-based scholarship program intended to improve the local economy.

More details on this proposal are in a report released in September 2020 by the Metropolitan Policy Program of the Brookings Institution,“Helping America’s Distressed Communities Recover from the COVID-19 Recession and Achieve Long-Term Prosperity.” Visit brookings.edu to find and download the complete 28-page paper.

The United States has a problem with distressed local labor markets. Addressing this problem will require providing the resources needed to significantly boost jobs in distressed areas — accompanied by some caps on counter-productive incentives.

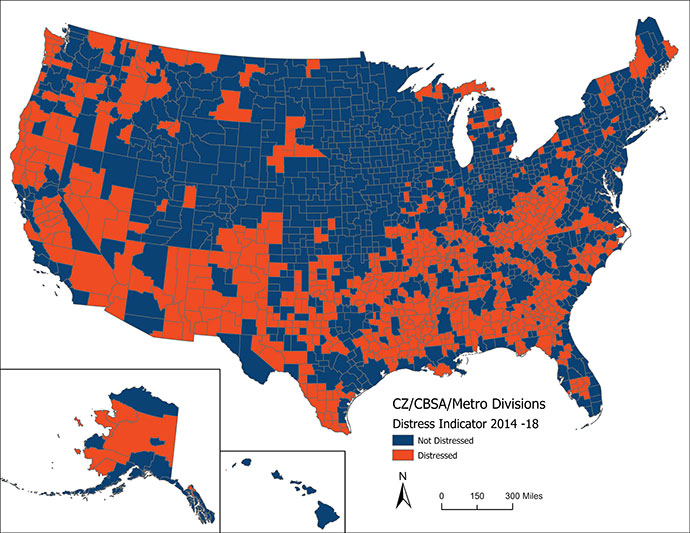

About 15% of the U.S. population lives in local labor markets whose employment to population ratio (“employment rate”) for “prime-age” workers (those ages 25-54) is at least 5 percentage points below the national average. (see map).

What state and local governments are currently doing to help these distressed areas is not working. Distressed local areas often do not have the resources needed to make their areas more competitive for job growth. Incentives at the state or local level often go to already-booming areas.

Over 90% of the resources devoted to economic development go to incentives, rather than to services to business to improve business inputs: infrastructure, customized training, research parks, manufacturing extension services, small business development centers, etc. Really turning around a distressed local economy requires public service investments.

Grant and Cap

What could the federal government do to help? First, the federal government could provide a flexible block grant, to boost economic development in distressed areas. The federal government did this on a pilot basis with the Tennessee Valley Authority program. At its peak in the 1950s, TVA provided assistance of over $300 per capita.

My proposal: a federal economic development block grant for the 15% of all local labor markets that are most distressed. This block grant could be used for a wide variety of job-creating infrastructure and public services. The block grant would be provided for at least a 10-year period. If we provided per-capita aid at similar levels to the TVA, the annual cost would be around $16 billion.

Based on prior estimates of the cost per job of public services, this block grant after 10 years would boost these distressed areas’ jobs by over 3 million. The gap in employment rates between these distressed areas and the nation would be cut by half.

Second, as a condition for receiving this block grant, state governments would have to agree that discretionary incentives would be capped, particularly in non-distressed areas. If we want to help distressed areas, targeting non-distressed areas is counter-productive.

These caps could be modeled after the European Union’s. In the EU, for large projects in non-distressed areas, incentives are limited to either 3.4% of the investment, or 3.4% of the first two years of the project’s wage bill. The EU-permitted incentives go up in more distressed regions; in the most distressed regions, they max out at five times larger.

Such an incentive regulation would have ruled out some of the largest bids for Amazon’s so-called HQ2. Some of these larger bids for this project exceeded $7 billion. Based on the public information available on this Amazon project, EU rules would have permitted an incentive bid of around $400 million in non-distressed areas, and $2 billion in the most distressed areas.

Distressed communities are diverse in racial and ethnic composition, and above the national average in their percentage of residents who are Black and Latino or Hispanic. Boosts in employment rates in these areas would particularly benefit lower-income groups, who are more likely to be out of work. This program would significantly improve job opportunities for residents of distressed areas and help the nation’s recovery become a tide that truly lifts all boats.

Helping distressed local labor markets should be a national priority. Achieving such a priority requires significant resources, such as this $16 billion annual block grant. It also requires putting some limit on excessive incentives being provided in non-distressed areas.

Timothy J. Bartik is a Senior Economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, in Kalamazoo, Michigan.