The beauty of living and working in Southern California’s San Bernardino County is its logistics-centered workforce, says B.J. Patterson, CEO of Pacific Mountain Logistics. “What I can find from an experience standpoint is often better than in other areas. That’s the draw,” he says.

The U.S. Navy veteran today heads the third-party logistics provider with a large facility in San Bernardino, not far from Ontario International Airport (ONT). He also sits on the San Bernardino County Workforce Development Board (WDB), which early in 2019 launched a new Workforce Roadmap in conjunction with the county’s Vision2Succeed Initiative (www.vision2succeed.org), designed to engage the community in a way that strengthens the skills of the local workforce, prepares them for career opportunities and supports and attracts business.

The roadmap came from research found in a new Labor Market Intelligence Report (LMI), published by the WDB in collaboration with the UC-Riverside Center for Economic Research and Development, which showed that San Bernardino County is experiencing an annual net migration of 25,000 people and has added more than 130,000 jobs since 2010 — a 27-percent growth rate.

“If you’re going to be in logistics, there’s no better place to be than here.”

Logistics is at the heart of that growth, as the region experiences record demand for industrial space. Tenants across multiple industries “have identified this market as a strategic location for growth,” according to a recent release from AXA Investment Managers – Real Assets, as the firm, along with Bixby Land Co., acquired a Class A industrial building in San Bernardino for $33 million.

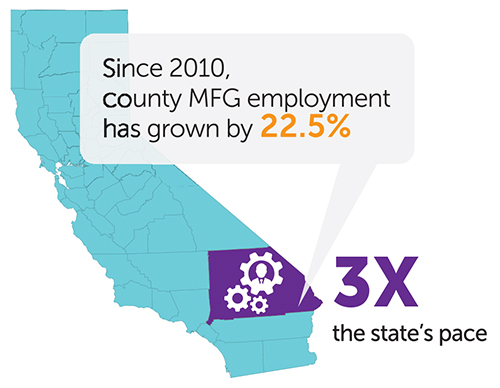

But manufacturing has grown jobs by 22.5 percent since 2010. And therein lies much promise, as automation and goods movement converge in Southern California. Could San Bernardino County have the right mix to manufacture and service the automation technology that’s entering the logistics arena faster than a delivery truck trying to beat the FedEx cutoff?

“Absolutely,” says Patterson. “That’s why vocational education is really important. There’s this myth that automation is somehow going to cause unemployment. I don’t think that could be further from the truth.”

His firm already takes advantage of partnering with area community colleges such as Chaffey College to gain access to interns and apprentices pursuing certifications. And he’s been suitably impressed.

“The young kids today at my company are not afraid of anything,” he says. “They were born in the age of technology. We’re rolling out a new system that will run our company, and the young ones, with very little training, are on it. They dive right in. They’re not afraid. It’s amazing how quickly they adapt … They’re willing and more than excited to do multiple things. Flexibilty is key in our industry — you might do X today, Y tomorrow and Z the next day. They enjoy that.”

With automation comes a whole new set of jobs that require a different level of certifications. “Electricians, millwrights, mechanics, electro-mechanics. Those jobs are high-paying too — between $75,000 and $85,000 a year — and there’s going to be a lot of them.”

‘Precipice of Change’

That’s where the Workforce Roadmap comes in. In addition to offering labor market intelligence, it will provide asset mapping and real-time economic data to help businesses and stakeholders better understand not only what has taken place in the county, but where the county is going.

“The county could hit that sweet spot where workforce development intervention fills a gap.”

“The only way to close the skills gap is to become predictive in nature, rather than reacting to changes after they’ve happened,” says Reg Javier, San Bernardino County Deputy Executive Officer, Economic and Workforce Development. “We know the number one driver of business and success is talent availability and acquisition. We want to mobilize an entire system and region around the talent production that will be driving that growth, as opposed to reacting to growth that happens to us.”

His best example jibes with Patterson’s observations from the field:

“We know our largest industry sector by far is logistics, distribution and warehousing, and that it is also susceptible to automation,” Javier says. “If we have a good portion of our largest industrial sector adopting technology, we will be one of the largest purchasers of that technology in the world. That means those machines will need maintenance, parts and so forth, so there is a natural push in the marketplace to be close to the customer. They’ll start locating here, then the manufacturers of those machines will locate here … you can almost see this diversification happening because of our roots.”

Javier himself has pulled up the roots. Like many in the county, he is a transplant.

“People ask me why I came here,” he says. “What I found was that San Bernardino County is on the precipice of real evolution and change. We have phenomenal leadership. Our county government is extremely progressive. Leaders at organizations in the community and in the school districts, are doing amazing work. I decided to come here because I wanted to be part of that, be a catalyst, and bring those folks together. We’re seeing the emergence of a really bright future.”

Adam Fowler, manager of Public Policy Research at the UC Riverside Center for Economic Forecasting and Development at the School of Business Administration and a co-author of the LMI, agrees that the county has “a laundry list of nice opportunities to be leveraged across many dimensions,” as the county’s wealth of logistics operations blossoms alongside growing public resources at ONT, at the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles and in the county’s population centers.

Those improving infrastructure assets also include sometimes overlooked players: the area’s two Class I railroads, Union Pacific and BNSF.

“The railroads have done remarkable work improving their level of service, to where we can get to Chicago in three days, faster on a train than a truck,” says Patterson of Pacific Mountain Logistics. “It’s a minor miracle.”

“We took a deeper look at the four core industries — warehouse, transportation, manufacturing and health care,” says Fowler’s co-author Alysa Sloan Hannon, manager, Sustainable Growth and Development, at the UC-Riverside School of Business Center for Economic Forecasting and Development. “San Bernardino County does face certain challenges around relative wages and educational attainment levels. But thinking about those industries, broader challenges and rapid technology advances, the county could hit that sweet spot where workforce development intervention fills a gap.”

In-Migration Up, But Commuting Is Too

Filling gaps is on everyone’s mind, including the gap in daily life caused by big commutes.

The past several years have seen an impressive influx of people: Between 2013 and 2017, more than 100,000 Los Angeles residents moved to San Bernardino County.

Javier points to an exodus from urban cores as well as the aging of a millennial generation looking for quality of life and a house they can afford. They find it in San Bernardino County, where home prices are 60 percent less than in neighboring Orange County and 50 percent less than in neighboring Los Angeles County.

At the same time, however, some 250,000 workers leave the county every day to work elsewhere. That’s not a big worry given that the county is near two huge metro areas. But it’s worth asking what kinds of work they’re leaving for, and looking at ways to keep workers around — including such things as a firm-by-firm scrutiny of wages (county wages are demonstrably lower than its neighbors) and development of lifestyle amenities that will attract employees to live and work in the county.

“Lots of people may not be changing where they work,” says Fowler, “but are making a home in San Bernardino County, and show up in the data as super commuters [over 90 minutes each way] who still have economic ties in Los Angeles County … so it is providing opportunities for folks wanting to own a home in the area.”

They’ll be glad to hear this then: “We have 100,000 housing units planned,” says Javier. As they’re built, they’ll be added to a new asset map and real-time data that are part of the WDB’s program, tracking everything from job search and employment services to demographic and educational attainment data.

The LMI found that if San Bernardino County had the same labor force participation rate (LFPR) as the comparison regions next door, there would be an additional 33,000 to 108,000 workers in the County’s labor force. One finding in the manufacturing sector is especially promising: From 2012-2017, the number of manufacturing workers commuting from Los Angeles County to San Bernardino County doubled.

Clean Tech Next?

Meanwhile, youths between 16 and 24 have a higher LFPR than their coastal counterparts, the study found. They’re the target audience for the county’s Generation Go! program, which exposes those young people to occupations they may never even have heard of. And that could lead to opportunities that are new to everyone.

“We found that the regulatory environment and this idea around green and clean regulation was a real opportunity in terms of competitive advantage regionally,” says Hannon.

After all, Fowler explains, the progressive environmental regulatory framework in California involving pollutants, emissions from goods movement and manufacturing put it more on par with the rest of the world than the rest of the United States. As such, “it’s a race to figure out those new ways of doing business,” he says. “Because a lot of the global economy is playing by the rules California is playing by now, it gives us the ability to both figure it out in an industry-specific context, and to be a leader in exporting that knowledge around the globe.”

He cites a recent visit by a Chinese delegation to learn about clean trucking initiatives around the ports.

With health care as an outlier, all the other target industries in San Bernardino County will see changes in their environmental footprint in the near future.

Hannon says she and Fowler were challenged to think about how the county gets to that proverbial “next rung up” on the economic ladder. They think clean tech could be one path forward — almost like a career pathway for an entire region.

“Use clean and green to train workers cross-sectorally,” she says. “Particularly around goods movement, there is a lot of activity around clean and green.

“Harnessing that expertise,” she says, “could be a strategy for workforce development.”

This Investment Profile was prepared under the auspices of San Bernardino County government. Employers interested in San Bernardino County Workforce Development Board programs may call (800) 451-JOBS or visit www.sbcounty.gov/workforce. For more information, contact the county Economic Development Agency at 909-387-4700. On the web, go to www.sbcountyadvantage.com.