Hurricane Maria made landfall in southeastern Puerto Rico on September 20, cutting a catastrophic, diagonal swath that covered the entire island. In addition to knocking out power and inflicting an ongoing humanitarian crisis across the already economically crippled US territory, the storm has slowed production at some of Puerto Rico’s dozens of factories that make vital drugs and other medical supplies that serve the world.

Near Humacao, Maria ripped off the roof of a Bristol-Myers Squibb plant. Seventeen miles inland, the eye of the storm passed south of Juncos, a town of 40,000 that counts Amgen (biopharmaceutical manufacturing), Medtronic (medical technology) and Becton Dickinson (medical devices) among its manufacturing core. Over the island’s interior, the eye crossed Jayuya, one of three Puerto Rican towns where Illinois-based Baxter manufactures critical intravenous therapies. Some 30 hours after landfall, the storm departed a shattered Puerto Rico near Aguadilla, where Canada’s Angitotech makes surgical instruments.

The effects on the island’s pharmaceuticals base, which counts around 80 research and production facilities, is perhaps most vividly reflected in the 90-odd drugs that now appear on the US Food and Drug Administration’s critical shortage watch list, up from 40 in Maria’s immediate wake.

Officials express concern about the ongoing supplies of varieties of IV saline bags, injectable amino acids for infants and the childhood leukemia drug methotrexate, all manufactured in Puerto Rico. FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who traveled to Puerto Rico to assess the damage, said in a late-November statement that until electricity is fully restored, “many firms will continue to run on generator power or require generators as a backup, and production levels will not return to their baseline levels.”

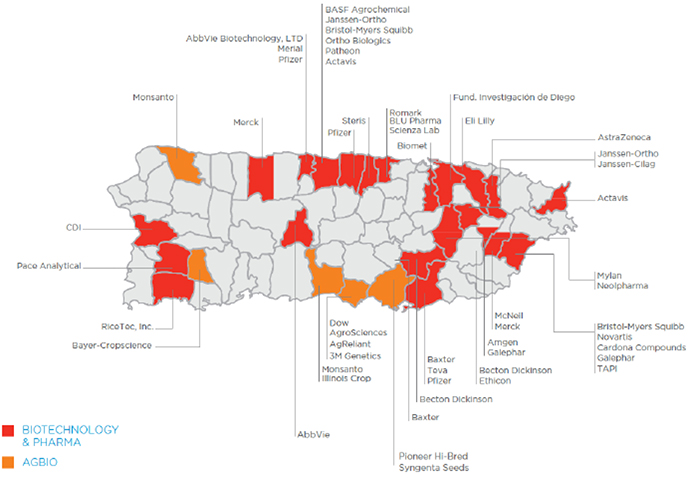

Life Sciences in Puerto Rico

On December 28, Texas-based Fluor Corporation confirmed it had completed work on a power line that serves the inland city of Caguas, where Mylan makes methotrexate, asserting in a news release that the line will “carry electricity to a pharmaceutical manufacturing facility.”

The Caguas line is one of four 38kv priority lines Flour identified as having been recently repaired, the other three near San Juan. Flour says it has more than 1,600 people working in Puerto Rico under contract with the US Army Corps of Engineers to help restore the island’s power grid, which was reported running at 65 percent in late December. Citing an official of the Corps, the New York Times reported December 23 that remote areas of the island might not have electricity until May.

Is Pharma at a Crossroads?

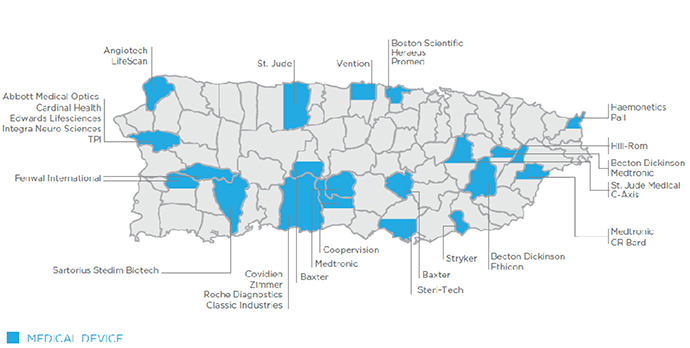

While some may think that tourism is Puerto Rico’s dominant economic driver, a bigger part of the island’s gross domestic product comes from manufacturing — pharmaceuticals manufacturing in particular. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices are the island’s leading exports, and the sector employs some 90,000 Puerto Ricans.

According to the FDA:

- Approximately 30 percent of Puerto Rico’s GDP in 2016 was driven by pharmaceuticals and medical devices.

- Approximately 30 percent of Puerto Rico’s manufacturing employees are employed by manufacturers of medical products, which include drugs, biologics and devices.

- Puerto Rico produces more pharmaceuticals for the US ($40 billon in value) than any of the 50 states or any single foreign country.

Puerto Rico became a hot spot for pharma in the 1970s, thanks to generous tax breaks from Washington. One of them allowed US manufacturing companies to avoid corporate income taxes on profits made in US territories. Drug and medical device makers that have migrated to the island include Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis and Pfizer. After a 1996 budget-cutting spree in Washington led to a 10-year phase-out of Puerto Rico’s incentives, its manufacturing industry, including pharmaceuticals, entered a decline.

Medical Devices in Puerto Rico

“Puerto Rico,” says Gabriel Hernandez, head of the tax division at BDO Puerto Rico, “enjoyed at least some form of tax incentives between the years 1921 and 2006. Over that period,” Hernandez tells Site Selection from San Juan, “the local economy grew from an agrarian place to a place of industry. These incentives played a role in skewing investment decisions in favor or Puerto Rico. Since the termination of those tax incentives our economy has suffered and lagged, which you could argue was due to the end of those incentives.”

Tax policy made in Washington may haunt Puerto Rico again. The Republican tax bill, which President Trump signed Dec. 22, treats Puerto Rico as a foreign country, and thus imposes a 12.5-percent tax on the income companies receive from their intellectual property. That could hit the island’s pharma industry. Puerto Rican officials lobbied hard for an exemption, but to no avail. Suggesting that mainland drug makers could pull out of Puerto Rico, the territory’s Governor Ricardo Rosselló has called the tax law “unconscionable” and “devastating.”

“Not creating an exception for Puerto Rico was a heavy blow,” says Gabriel Hernandez. “By narrowing the margin for the pharmaceuticals industry, it created an even more negative bias against Puerto Rico.”