The nation’s first offshore wind farm may have been built off the coast of New England, but it came to fruition with a healthy measure of Cajun ingenuity. More than a half dozen Louisiana contactors, all with experience in the Gulf of Mexico’s offshore oil and gas industry, played fundamental roles in planting Block Island Wind Farm’s five massive turbines in the waters off Rhode Island. Skills such as those soon will be deployed on a multitude of similar projects closer to home.

Already the source of the vast majority of U.S. offshore oil production, the Gulf of Mexico is on the cusp of an offshore wind boom the likes of which now is unfolding along the Atlantic shelf. Louisiana, with its army of oil and gas engineers, muscular maritime workforce and established industrial infrastructure, is eager to take the lead among Gulf states and would appear to have the chops to do so.

“The Gulf of Mexico is built around the offshore oil and gas industry,” says Walt Musial, principal engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), and leader of the federal agency’s offshore wind research platform. “The capabilities you see in places like Louisiana translate very directly to offshore wind.”

Musial served as lead author of a 2020 NREL study that concluded that the Gulf of Mexico, with its shallow, warm waters, smaller average wave heights and proximity to existing oil and gas infrastructure, offers numerous advantages for offshore wind, with the potential to develop up to 508 gigawatts of electricity, twice the volume currently consumed from Texas to Florida.

“We couldn’t come close,” Musial tells Site Selection, “to tapping the whole thing.”

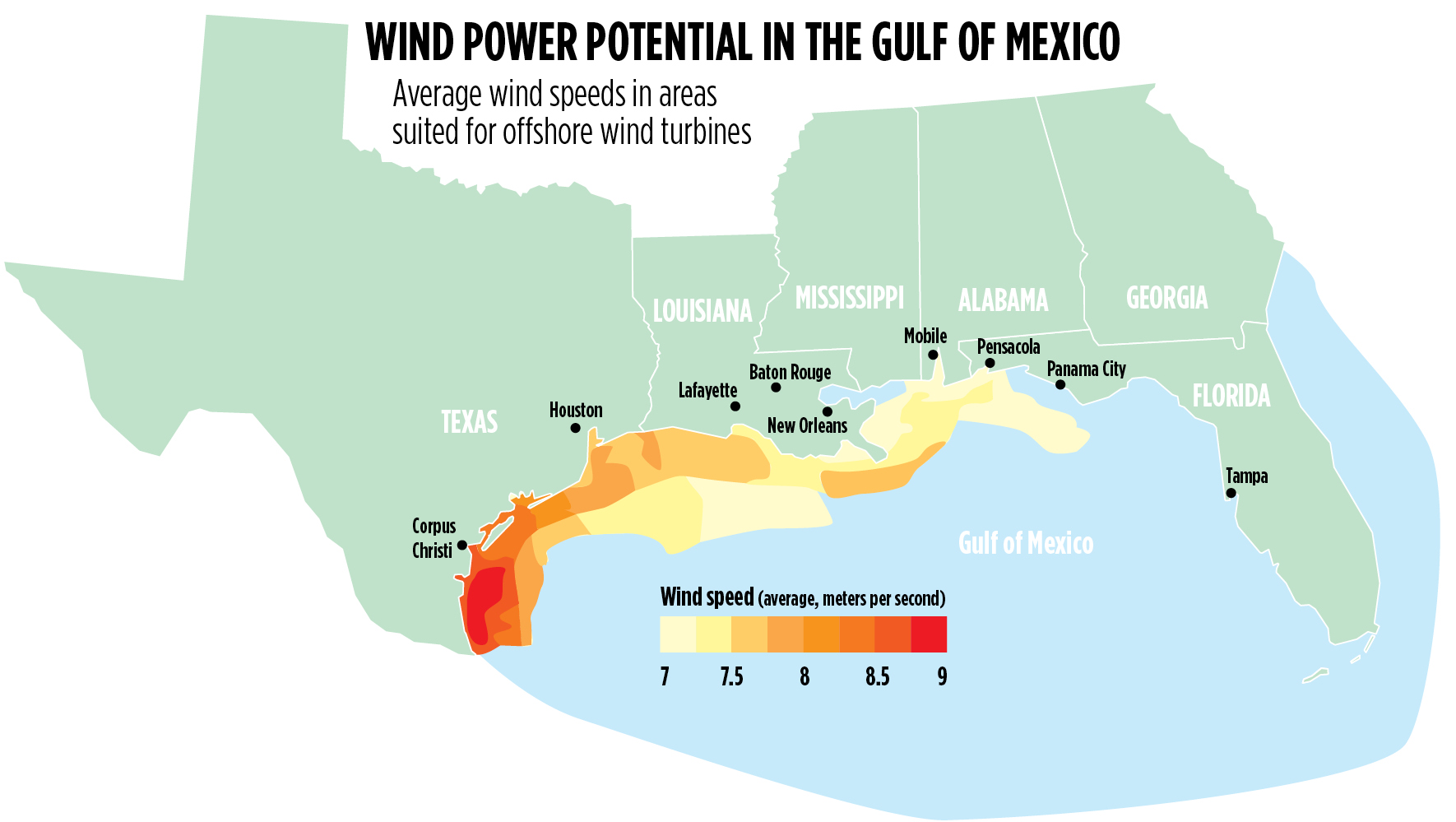

The waters off Texas and Louisiana offer some of the Gulf’s strongest wind speeds.

Source: NREL

The NREL survey estimated that, during construction, a single, 600-megawatt wind “plant” in the Gulf could support some 4,470 jobs while creating $445 million in GDP. Multiply that many times over, and it’s easy to see why Louisiana Gov. Jon Bel Edwards is aggressively promoting offshore wind. Leader of the first Gulf state to establish net-zero greenhouse gas emission goals, Edwards successfully led a charge to petition the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to formally launch the process of mapping potential lease areas across some 30 million acres of the Gulf.

“There’s no better example,” Edwards told a panel last June, “of how improving the environment and the economy can go hand in hand than offshore wind development.”

‘Turnkey Ready’

It’s a moment Jim Martin, CEO of Gulf Wind Technology, has long anticipated. Martin arrived in Louisiana in 2010 to establish the technology hub of the former Blade Dynamics, a UK-based wind energy venture, at NASA Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, where the Saturn V rocket once was built. He later served as senior director of blade platform deployment for LM Wind, a leading global blade manufacturer, whose New Orleans facility operates the country’s only wind engineering technology center. He launched Gulf Wind Technology in January.

“We’ve spent the last decade exporting ideas,” says Martin. “What I’ve done now to set up a company focusing specifically on wind energy in the Gulf of Mexico.”

Gulf Wind bills itself as the leading wind turbine rotor technology specialist in the United States. The new company is based at Avondale Shipyard, a railroad-connected, former Huntington Ingalls property spanning 254 acres along the New Orleans Mississippi River waterfront. Recently redeveloped to the tune of $100 million and being marketed to large-scale manufacturers, Avondale Shipyard, believes Martin, could serve as a staging ground for the development, production and transport of offshore wind components.

“Avondale Shipyard,” he tells Site Selection, “is one of the places on the Gulf Coast that is turnkey ready and already is dealing with wind turbine blades. It’s a perfect example of an infrastructure that is very much ready for the growth of offshore wind.”

The New Orleans region, says Martin, also has the dock space to handle incoming goods, the means to convert steel and composites into finished products such as blades and foundations, and the maritime prowess for offshore installation.

“We know we can do this,” says Louisiana Economic Development Secretary Don Pierson. “We are very well positioned not just for the fabrication and installation of wind energy in the Gulf, but along the East Coast and other locations. So, when the phone begins to ring with investors willing to back these investments,” Pierson tells Site Selection, “Louisiana will be ready to secure that business.”

To-Do List

The question is when that will happen.

Alone among states in the Gulf region, Louisiana has established an initial target for offshore wind capacity, an ambitious five gigawatts by 2035, enough to power more than 800,000 homes. Five gigawatts, according to Musial, would require five wind plants, each consisting of around 65 offshore platforms. Martin believes that construction, given the exacting federal leasing and permitting framework, is at least five years away.

In the meantime, engineers must solve the challenge of hurricane-proofing wind installations, a consideration that’s less acute along the East Coast or offshore northern Europe, where offshore wind technology first was developed. The Gulf’s lower prevailing wind speeds also are likely to necessitate the development of ever-larger turbines and blades to extract energy at scale. Tested at LM Wind in New Orleans, GE Wind’s Haliade-X is the biggest machine presently on the market. Its blades stretch to 107 meters. Longer blades are on the way.

The ultimate test, though, Musial and Martin agree, will be one of economy. Musial believes that developing offshore wind in the Gulf of Mexico, due mostly to the Gulf’s lower relative wind speeds, is likely to be more costly than it is in the Atlantic, but perhaps only nominally so.

“It’s going to be incrementally more expensive, but it probably won’t be a huge hit. There are offsetting factors,” he says, “including the fact that you have local supply chains in the Gulf that are available already.”

An immediate need is to persuade potential investors to throw skin in the game.

“What we have to do,” says Martin, “is to demonstrate that there is a value proposition that can be achieved with wind in the Gulf of Mexico, to run a pilot project to show that. That is something we are working on as we speak.”