Evolving priorities open new avenues for a stalwart Texas industry.

Among the many economic sectors in which Texas is a national leader, mining flies under the radar. Yet the Lone Star is identified in the U.S. Geological Survey’s 2025 Mineral Commodities Survey as America’s second-ranked producer of minerals, its 2024 valuation having reached $9.7 billion. Texas produces more crushed stone, dimension stone and cement than any state in the country and is ranked No. 2 for construction sand and gravel. It’s also a leader in limestone production.

“We’re not talking gold or silver, but a lot of stuff that most people might consider somewhat boring,” says Brent Elliott, research associate professor at the Bureau of Economic Geology at The University of Texas at Austin.

Boring, perhaps, but economically crucial. Indeed, the vast majority of Texas’ mineral production goes toward construction, reflecting the state’s growth spiral. It’s hardly a coincidence that Texas also leads the nation in cement consumption.

Access to the booming Texas market was a motivation for Ireland’s CRH to pay a whopping $2.1 billion last year for a collection of assets from Martin Marietta Materials, anchored by the 2,000-acre Hunter Cement Plant in New Braunfels. The plant’s annual production capacity of 2.4 million tons ranks it among the top 10 in the United States.

CRH also claimed ownership of cement terminals in the Houston and San Antonio regions, as well as 20 concrete plants spread across San Antonio, Austin, Round Rock and Bastrop.

“Our ability to leverage our cement expertise and technical capabilities will enable us to enhance and optimize our existing footprint in Texas, resulting in significant synergies and opportunities,” said CEO Albert Manifold. “We also believe there is significant potential to unlock additional growth opportunities across an expanded footprint in this attractive growth market.”

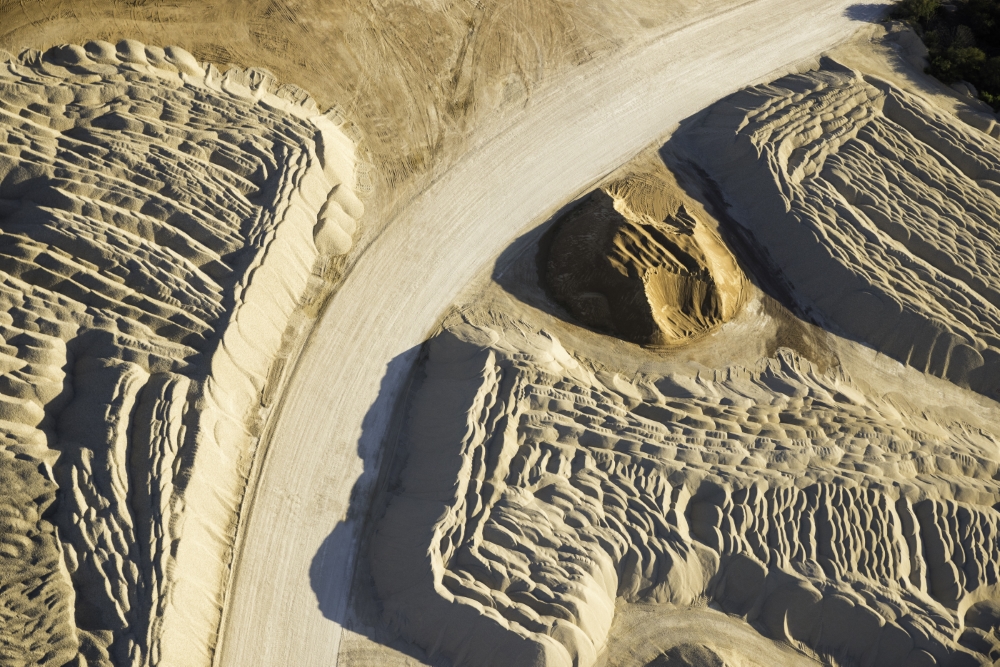

Texas is a top producer of sand for construction projects.

Photo from Getty Images/dscz

Uranium Set to Expand

Texas being at the forefront of a nascent national project to resurrect the nuclear power industry, new opportunities are emerging to leverage the state’s vast deposits of uranium. Texas, according to the National Uranium Resource evaluation, holds 24% of all U.S. speculative uranium resources.

“Considering the recent restriction of global supply and continuing interest in growing electricity generation from nuclear energy,” reads a 2024 report prepared for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, “there has been a noticeable interest to increase uranium production across the U.S., and particularly in Texas.”

Texas was one of the most active and prolific uranium mining locations in the U.S. before the 1980s, when prices declined in tandem with a standstill in new nuclear plant construction.

“But suddenly,” says Elliott, “we’re starting to crank up our uranium mining operations.”

A significant number of uranium mines — in various stages of operation — are located amid sandstone formations across a dozen or so counties in the Texas Gulf Coast region. EnCore Energy, which calls itself “America’s newest uranium producer,” recently launched production at two South Texas sites and hopes to bring four more online by 2027. In Golliard County, Uranium Energy Corp. plans to mine 420 acres of the Evangeline Aquifer using in-situ recovery, which allows for mining far beneath the surface.

By one estimate, Texas could supply 40% of U.S. uranium demand by 2030.

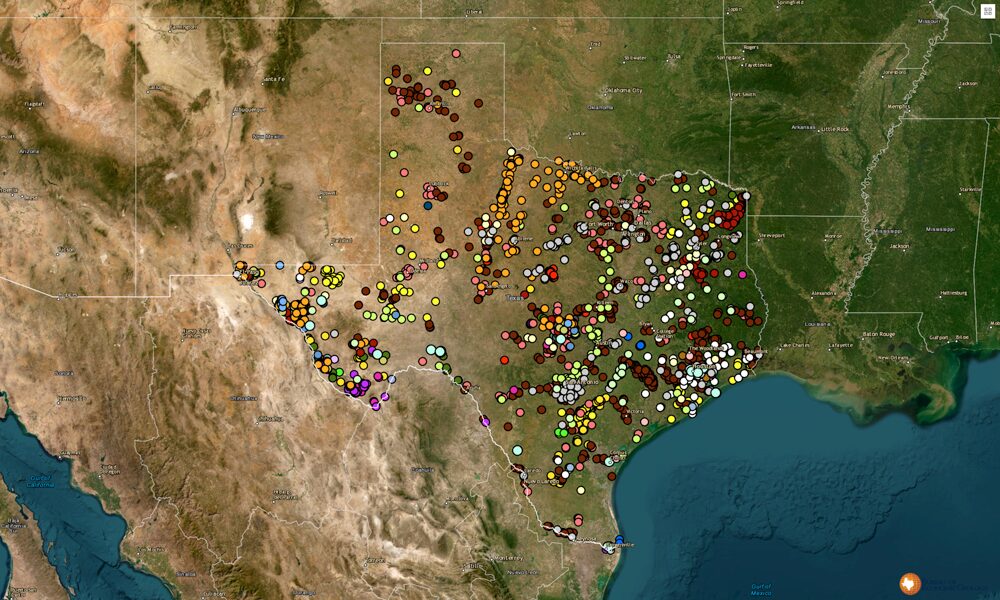

Texas Mineral Resource

Photo courtesy of University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology

Rare Earth Minerals Poised for Investment

Evolving national priorities are opening still another avenue for the Texas mining industry, namely the recovery and processing of rare earth elements and other industrial minerals essential to the development of advanced electronics. Supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Defense totaling $288 million, Australia-based Lynas Rare Earth is developing a rare earth processing facility in the coastal town of Seadrift that could process an estimated 25% of the world’s supply of rare earth element oxides when it begins operations this year.

Lynas is considered the world’s largest producer of rare earths outside of China.

Its Texas operation is expected to create 300 direct, indirect and induced jobs when fully operational. The 150-acre site, the company says, “will allow for co-location of Heavy Rare Earths and Light Rare Earth separation and processing as well as potential growth opportunities such as downstream processing and recycling.”

In Hudspeth County in extreme West Texas, the 1,250-foot Round Top Mountain holds hundreds of millions of metric tons of rare earth elements just waiting to be extracted, a prospect that could represent a significant step toward breaking China’s monopoly on rare earth mining and processing. Two companies — USA Rare Earth and Texas Mineral Resources Corp. — have put millions of dollars into studying the mountain’s potential profitability. The companies estimate the deposits there are worth about $1.56 billion. That they haven’t yet gone forward, says Elliott, is largely due to the vagaries of commodity prices and the high cost of separating rare earths from minerals of less value.

“They have it all set up,” says Elliott. “I just think they’re waiting for an investor to come in there and actually do it.”

And, he says, “there are probably more than 100 of these kinds of igneous rock bodies across West Texas, and a lot have as much or more rare earth concentration as Round Top does. It’s a matter of getting investors lined up.”