Development of renewable energy resources is increasingly critical to meeting demand for non-carbon-based energy, as well as state and federal emissions standards. But development is easier said than done. The western U.S. is home to vast amounts of renewable energy resources, but environmental and transmission issues must be overcome before those resources can become the economic engines they might be. Alternative energy hubs are thriving around the West — Arizona’s solar energy industry is the obvious example. But the potential is vastly greater than what exists today.

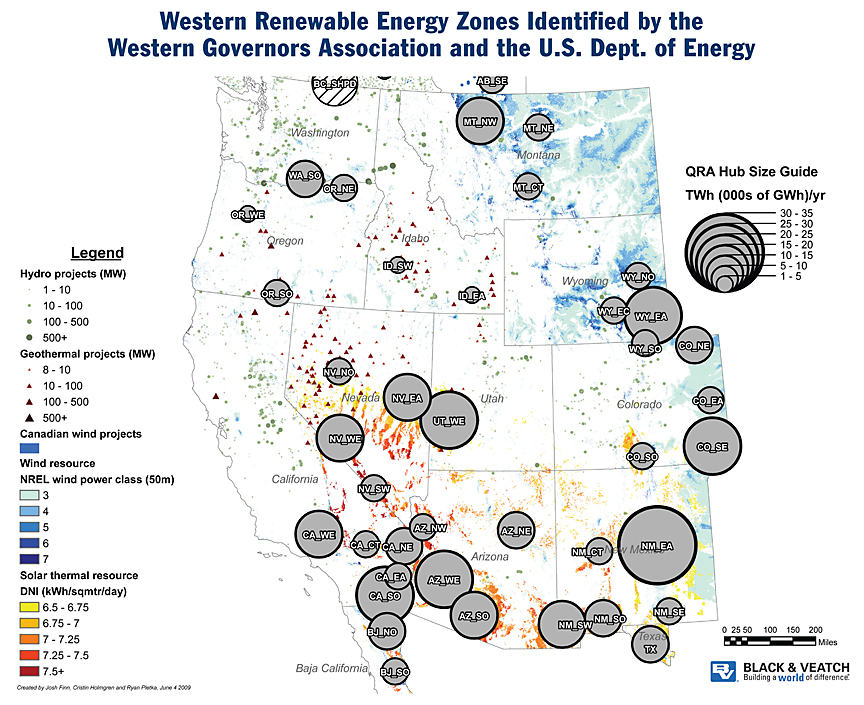

In June 2009, the Western Governors’ Association (WGA) and the U.S. Department of Energy released a joint report, the Western Renewable Energy Zones – Phase 1 Report, that took the first steps toward identifying those areas in the Western Interconnection (the 11 westernmost states of the lower 48) that have both the potential for large scale development of renewable resources and low environmental impacts. The report includes a WREZ Initiative Hub Map that can be viewed at www.westgov.org/wga/initiatives/wrez/index.htm — copious footnotes and graphics preclude inclusion of the map in its entirety here. The map, which includes Canada’s British Columbia, shows areas of regional renewable resource potential so that interstate transmission lines can be evaluated. The hubs are shown in proportion to the amount of electricity they could generate in terawatt hours from hydro, geothermal, wind and solar sources over the course of a year.

WGA Chairman at the time and former Utah Gov. Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., said the parties had achieved “an aggressive goal of bringing together in less than one year a large number of stakeholders to identify areas that have the most promising renewable energy resources. Their efforts,” he added, “are an important first step in developing cost-attractive renewable energy resources across the West and the high voltage transmission that will ensure this electricity can be delivered to demand centers.”

Secretary of Energy Steven Chu characterized the significance of the report this way: “To harness the incredible renewable energy potential of the West, we need to know where that energy can be generated and how to move it to where people live. This study is a necessary step for creating a clean energy economy.”

The U.S. Departments of Interior and Agriculture and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission were also involved in the initiative. Participants in the WREZ process included renewable energy developers, tribal interests, utility planners, environmental groups and government policymakers.

Where Terawatts Are the Standard

Today, Phase 2 is under way. The WGA governors are working with utilities and the Western Electricity Coordinating Council to evaluate transmission needs to move power from the preferred renewable energy zones. They will work to improve the integration of wildlife and environmental values in decisions on the development of generation and transmission associated with these renewable energy zones. Stakeholders have agreed to work with WGA to coordinate purchasing from the desirable renewable energy zones to demand centers and to coordinate interstate cooperation for renewable energy generation and transmission.

The gist of the project, says Rich Halvey, WGA’s energy program director is this: “If we were going to look at trying to develop large scale, renewable developments that would sustain a large transmission line, where would those areas be? Other systems are designed to get 80 or 100 megawatts out of a development, but we were looking to get more like 1,500 or 2,000 megawatts. That would allow us to sustain the construction of a fairly large, high-capacity transmission line.”

Renewable developers routinely make the case that they do not have access to transmission, says Halvey.

“The difference between renewable energy and fossil-fuel energy is you can bring fossil fuels to the plant, but with renewable you have to bring the plant to the fuel.”

In the West, renewable energy sources are typically in locations that lack infrastructure — energy or otherwise — and by some estimates, the cost of transmission infrastructure can run upwards of $1 million or more per mile.

“You can quickly take a project that looked promising and kill it by having to pay for the transmission,” says Halvey.

The WREZ project also serves to gauge the development potential of western regions. Locations for wind or solar energy projects were eliminated if the terrain was too steep, for example, or if urban growth would prevent development. Wildlife advocates, not surprisingly, had issues with all of the areas identified as potential renewable energy hubs.

“The report doesn’t talk much about wildlife,” says Halvey, “but it does talk about the value of the resource. Since we released the report, we’re getting a better handle on the wildlife data, and we’re going a step farther in that area. We know that of the 30 or so nodes we identified, not all will have the same appeal. We want to focus future analysis of ‘developability’ on those that would be of the most interest to the wholesale buyers of the power — the utilities.”

Cost-Benefit Analysis On a Big Scale

The Phase 1 Report and subsequent analysis point to bigger issues, says Halvey. WGA and parties working on the report assumed that if the energy hubs were identified and analysis of their development potential was made available, people would beat a path to their doors, ready to develop energy projects.

“When states talk about the green-energy economy, they don’t mean bringing wind in from a distant location, but rather developing it locally,” Halvey explains. “So even when you have statewide renewable portfolio standards as many states do, if the cost of domestic production is slightly higher than long-distance production, the benefits of economic development jobs, sometimes permanent ones, may outweigh the cost difference in deciding what to do.”

Secondly, says Halvey, renewable developers are reluctant to gamble. The bigger the energy hub, the more environmental impact and land use work will need to be done, and more jurisdictions will come into play.

“Bringing energy from Montana to southern California involves four states and their land use agencies and public utilities commissions and so forth. If you’re a solar project developer with a tax credit that you know expires in eight years, and you know it will take 10 years to get the project put together, you’ll have a harder time getting financing, for one thing.” So developers without a guarantee that the larger projects will get financed and built are understandably reluctant to proceed. “You can only go so long spending borrowed money — at some point you want revenue coming in.”

Developers are more eager to proceed in areas in which they know the development potential is high.

“They may make a lot of money on a really big project,” says Halvey, “but they may have to wait a lot longer without a revenue stream coming in than they can sustain.”

A National Standard?

Halvey says utilities have proposed numerous transmission lines in the western U.S., but few of them have someone at the other end who has agreed to buy the power. They are under pressure from states to develop energy resources domestically, but they are hesitant to jump into the lacking-transmission issue with both feet.

“We are running a series of alternative future scenarios — everything from making assumptions about the penetration of energy efficiency and distributed generation, such as solar panels on houses, to the future of plug-in electric vehicles to carbon sequestration from coal plants — and simultaneously looking at water and wildlife issues,” says Halvey. “What we hope comes out of all this work is something that makes the case that transmission lines need to be built, primarily to open up renewable energy.

“But there’s a huge wild card in the national greenhouse gas emissions standard question,” he continues. “If there is one, and we need to inject a lot of renewables into the system to meet a standard, then all of this discussion about how renewable developers and utilities operate and how states build their green economies takes on a heightened significance.”

What is the Western Governors’ Association interest in all of this? These are somewhat long-term scenarios, after all.

“If we’re going to do this [renewable energy development on a large scale], then we are going to need to look at a regional solution,” says Halvey. “The Western Interconnection is a unified grid — there are lots of utilities, but everyone’s moving electricity on essentially the same grid. We’re not going to solve a fairly substantial problem like having reliable electricity generation and transmission system and grid by allowing everyone to plan in a vacuum. This regional perspective says we can look at reasonably priced, technologically feasible solutions because we’re looking at them on a large scale.”

Policy Building Blocks

Phase 2 is about the future energy scenarios Halvey described. “The hope here is that we will be able to see that no matter what you assume, there will some need to revamp the system. Whether you assume a fairly aggressive greenhouse gas emissions standard or a fairly slack one, or a lot of energy efficiency or not so much, nuclear or no nuclear, we’ll have a sense of where we need to direct policy,” he says. “The issue for the governors is that, armed with that information, they and legislators can look at policies and programs and incentives that will facilitate the best solutions to this regional provision of electricity and transmission.

“Because of the physics of the grid, you cannot put large amounts of electricity on it haphazardly. You have to balance the system consistently. The trick for the people managing this system, this regional grid, is to get the electricity from where it’s being generated and there is excess to where it is needed. The system has to handle the worst day you can throw at it.

“At the same time,” he adds, “the governors are highly concerned about doing something that is cost effective. Our challenge is finding an optimal generation mix that will keep electricity prices reasonable and keep the system operating reliably. We’re trying to get ahead of the game. If regulations and standards are coming, and if we want to be serious about increasing the renewable energy that’s on the system, we need to be working on it now.”

DESERTEC Energy Plan Advances

A joint venture comprising energy-related companies and major European banks is pushing forward with the DESERTEC Industrial Initiative (DII). Its objective is to analyze and develop the technical, economic, political, social and ecological framework for carbon-free power generation in the deserts of North Africa. DESERTEC has an ambitious $555-billion plan to develop a renewable energy zone across the deserts of the Middle East and North Africa.

The DII was founded to pave the way for the establishment of a framework for investments to supply the MENA region and Europe with power produced using solar and wind energy sources. The long-term goal is to satisfy a substantial part of the energy needs of the MENA countries and meet as much as 15 percent of Europe’s electricity demand by 2050.

The DESERTEC concept, which describes the perspectives of a sustainable power supply for all regions of the world with access to the energy potential of deserts, was developed by the TREC (Trans Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation) Initiative of the Club of Rome, a non-profit organization independent of any political, ideological or religious interests. Its mission is “to act as a global catalyst for change through the identification and analysis of the crucial problems facing humanity and the communication of such problems to the most important public and private decision makers as well as to the general public.”

Dr. Gerhard Knies, chairman of DESERTEC and CEO of TREC, estimates that by 2020 there will be power plants producing 15 to 20 gigawatts of power. That will require establishment of transmission lines and agreements between the EU and North African countries, Knies said. There will be a transition from local generation of power to a more international approach, according to Knies. Different sites of wind energy in the North Sea and African Atlantic shorelines, and the solar energy sites in the Sahara, will need to integrate with local renewable energy sources.

As of April, DII has 17 members, including ABB, Schott Solar, Siemens, Deutsche Bank, HSH Nordbank, M+W Zander and Saint-Gobain Solar. Among the DII’s main goals are the drafting of concrete business plans and associated financing concepts, and the initiating of industrial preparations for building a large number of networked solar thermal power plants distributed throughout the MENA region.

Besides the opportunities for business and for meeting government climate-change goals, members say other potentials include:

- Greater energy security in the EU/MENA countries;

- Growth and development opportunities for the MENA region as a result of substantial private investment;

- Safeguarding the future water supply in the MENA countries by utilizing excess energy in seawater desalination plants.

“The Desertec Industrial Initiative’s proposal to meet a large percentage of Europe’s energy requirements with renewable energy sources located in North Africa can help reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change,” said Luis Atienza, chairman of Red Electrica de Espana, which recently joined DII. “But this proposal can only be realized if power supply grids with high capacities are used and the countries bordering on the Mediterranean are involved. Via its branch Red Eléctrica Internacional (REI), Red Eléctrica will contribute to the development and operation of such power supply systems and also act as a link between north and south.”

Saint-Gobain Solar of France is one of the most recent companies to join DII. “In cost terms, solar thermal energy is one of the most promising sources of electricity for decades to come,” said Fabrice Didier, managing director. “To make this competitive, cooperation between companies is essential. The Desertec project helps set the framework for such cooperation.

“In addition to playing an active role in the photovoltaic sector, Saint-Gobain Solar develops and offers various key components designed for solar thermal plants, notably mirrors, receivers and heat storage units,” said Didier. “We are delighted to join this initiative and contribute to establishing a sound industrial base for solar energy.”