![]()

![]()

Magnetic South

ome claim Alabama’s name comes from the Native American expression for “Here we rest.” Others say it means “thicket clearers.” Both meanings resonated when it came to ThyssenKrupp’s decision to invest $3.7 billion and hire 2,700 to man a combined carbon and stainless steel manufacturing complex in Mt. Vernon, Ala., in north Mobile County.

The location had passed every test, and both the corporate and economic development project teams had chopped their way toward what the head of Thyssen- Krupp’s team called “a brilliant result.”

The company was so confident in its business case that its board approved the plan weeks before 79 percent of Alabama voters on June 5 ratified a constitutional amendment that would help fund the deal’s incentive package worth some $811 million, including $400 million in incentives approved by the Alabama Legislature in early 2007.

It was by no means a cinch, even down to those final days before Gov. Bob Riley got the 5:37 a.m. call on Friday, May 11, and “gave the high sign” to his wife Patsy. Early in the week, Riley and Neal Wade, head of the Alabama Development Office, were down near Mobile trying to accomplish a bit more, urging all governments in the area to get on board to help with their own incentives, in order to beat out the finalist site in St. James, La.

“Throughout that week, we were dealing with issues related to infrastructure and logistics, just so they were very comfortable when they took their recommendation to the board,” says Wade. “On that Thursday, literally, there was an issue related to logistics.”

As it turned out, Louisiana’s total incentive package came to more than twice that of Alabama’s.

“I’m glad I didn’t know,” says Wade with a laugh. “I believe we put a package on the table that the governor could defend to taxpayers.”

While a media focus on money seemed appropriate to a company whose first foray to the U.S. 170 years ago involved the manufacture of coin minting machines, cash incentives were not top- of- mind.

Trite as it may sound, teamwork was the key, says Thomas Woelker, senior vice president, head of business integration for ThyssenKrupp Steel AG, and the senior project manager over a team of more than 100 individuals who worked on “Project Compass” for more than 16 months. He recently made his 18th trip to the U.S. since February 2006.

“It’s for centuries, not weeks or months,” says Woelker of the project and its import for the company and community. He describes it as two projects: a site plan that would integrate operations from the company’s carbon and stainless divisions, and a site selection process that would dovetail with that plan. The team featured in- house logistics, financial, human resources expertise, as well as outside leadership from Cushman & Wakefield.

“The teaming process is so important,” says Woelker, not only for all the stages of site selection, but the implementation he and his team in Mobile are now overseeing. “The next stage will be more complicated than it was in the last year or so. We need to have the right teams in place.”

“We hit every major milestone on the critical path of the project, which was very important,” says Bob Hess, who with firm principal Andy Mace led the advisory team from Cushman & Wakefield Global Consulting. “Rarely will you find projects this complex that aren’t derailed politically, emotionally, by the economy and so on. It comes back to the integrity of the company – they were very serious about this strategy.”

“They were extremely committed and organized,” says Mace. “They had very strong ideas about design, and strongly organized teams that were incredibly effective. Our job was really to keep up with them, to organize our capabilities to react to theirs.”

That included partnering with further outside firms in order to bring expertise to the table in short order: Martin Associates on port issues, MACTEC on environmental issues and logistics and supply chain specialists at St. Onge.

“The last word at all the team meetings was ‘accelerate,’ ” says Hess, who calls this project “the crown jewel” of his 23- year career in global corporate location consulting.

Coordinating the information all of those experts produced was important too, says Christian Koenig, public and government affairs director for ThyssenKrupp USA, noting the welter of languages, time zones and jurisdictions that had to be aligned.

A project manager by background, Woelker says this was his first site selection project. He says staying focused and systematic was central to the process, but so was staying loose.

“A good 80- percent solution is a good solution,” he says of the internal negotiations as the team developed its market analysis while simultaneously winnowing its site candidates from 70 to 17 to the final two. “You don’t need to go into every picky detail.”

That might come as a surprise to those fielding the requests for information over the course of the past year and a half. Without divulging state names, Woelker and Koenig say the search focused initially on the

major waterway systems of the U.S., from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River delta.

“We went from 20 states and 67 sites to 33 sites we visited in person, spending an hour or two at each site with utility service providers and economic developers” says Mace of C&W’s work. “We narrowed it to 12 sites in about 8 states that were preferred sites, visited them with the client initially last summer, quickly brought it down to five, and then the finalists were sites in Arkansas, Alabama and Louisiana.” Arkansas was eliminated in January 2007 as the ThyssenKrupp search process went public.

The search had kicked into high gear once ThyssenKrupp ran into legal roadblocks in its attempted acquisition of Canadian steelmaker Dofasco. The company put together its intelligence on sites based in part on its cumulative experience in NAFTA territory: In addition to operations in Canada and Mexico, there are 70 companies in the U.S. employing approximately 25,000, with U.S. sales of approximately $9.7 billion.

The company’s heft was evident in the plea from U.S. Steel, a longtime denizen of Alabama, to Gov. Riley to consider the domestic competitiveness implications of pursuing the ThyssenKrupp deal. Asked about that request, Gov. Riley tells Site Selection, “I can understand why they sent the letter. But on the other hand, this project was going to be built somewhere in the southeast, so it’s not like you would remove the competition.

n Tuesday, July 3, Thomas Woelker, senior VP, ThyssenKrupp Steel USA; Dr. Ulrich Albrecht-Frueh, CEO, ThyssenKrupp Stainless USA; John Baker, president, Thompson Engineering; and Dr. Marcus Boening, vice president and CFO, ThyssenKrupp Steel USA (L-R), celebrated the signing of the geotechnical testing contract with the first soil sample from the ThyssenKrupp site in Calvert, Alabama. Thompson will conduct numerous soil tests on the future site of the facility and the marine terminal that will be constructed to allow for the loading and unloading of barges traveling on the Tombigbee River. A major component of the contract calls for the drilling of 148 soil test borings on the facility site and 26 soil test borings in the marine terminal area to depths ranging from 20 to 150 feet. These tests will help determine the number and types of foundation systems required for the facility and terminal. Thompson Engineering?s testing will begin in July. “We?re very excited to announce that this first contract was awarded to an Alabama-based company,” Bob Soulliere, CEO of ThyssenKrupp Steel USA, LLC, said. “We are committed to using local contractors and suppliers to the extent possible.”

That being the case, I wanted them in Alabama.”

Plenty of other companies spoke up too.

“We probably had 40 different German companies write letters talking about their experience in Alabama,” says Riley, including frank but universally positive assessments of the state’s work force and its training programs offered via AIDT. “The best recruiters we have are the people who have located here over the last 10 years,” he says.

Wade says leaders from Degussa and Mercedes met with ThyssenKrupp officials multiple times, and they did so privately. “One rule of thumb is we set these up and we get out of the way,” he says.

Alabama’s partners also included governors and U.S. senators in neighboring states Florida and Mississippi who pledged to look at the project as a “local” project – something that ought to help considerably during that next stage and beyond. The sense of team was further cemented by the participation and commitment of officials in Escambia, Baldwin and Washington counties, and even ancillary support from counties in Mississippi, as officials look for ways to share the costs initially pledged by Mobile County.

“South Alabama looked at the project as their economy- changing project,” says Wade, their “Mercedes.” Company leaders expect the changes to ripple across the region, even as far as runner- up Louisiana. Closer to Mobile, southeastern Mississippi is certainly taking notice.

“We realize the impact in Jackson and George counties,” says Gray Swoope, director of the Mississippi Development Authority, who has worked with Wade on a bi- state initiative to transform the economy of the “Black Belt” region of western Alabama and eastern Mississippi. “When you start putting over $3 billion in a region, that definitely has a big ripple effect.”

“$3.7 billion is, frankly, a lot,” deadpanned Bob Soulliere, president and CEO of TK Steel and Stainless USA, at the announcement. Communicating the scope and economic impact of this steelmaking site was part of the challenge, say people on all sides. The project could employ as many as 29,000 construction workers, and will eventually have approximately 7 million sq. ft. (650,300 sq. m.) under roof on its 3,500- acre (1,417- hectare) site.

“The biggest incentive packages we had going into this were for Honda, Hyundai and Mercedes, but if you took all of those investments and added them together, it wouldn’t be as much [impact] as this one project is going to have,” says Riley, who adds he had never spent so much time on a project before. The superlatives don’t stop there: “I’ve never seen a project that had this much due diligence to it,” says Wade.

One way to convey the scale was to bring potential site developers to the company’s integrated steelmaking site in Duisburg, Germany, the biggest steel production site in Europe and one of the biggest in the world, which is also seeing hundreds of

millions of dollars worth of expansion. Woelker says that got the message across.

“Rail companies, ports, economic developers and power companies would ask us if we had our units right, it was so extreme,” says Mace. “The acreage, electrical and natural gas requirements, water requirement – it’s really beyond words.”

“Metals analysts and others kept saying ‘What are they thinking? Nobody is building complexes this big,’ ” says Hess. “What the market doesn’t understand is this company is truly committed to quality and its customers. It wants the best technology and business processes, and has a well thought out market entry strategy.”

Shipping solutions, cost of power (Louisiana’s effort was said to be hurt by that state’s reliance on gas) and site infrastructure and incentives assistance tipped the balance toward Alabama. One novel solution to a vexing problem was a new $115- million terminal on Pinto Island for the transloading of 3 million tons a year of Brazilian steel slabs to barges.

“The site in Louisiana we knew had a logistical advantage, because they could take the Panamax ships straight up the Mississippi,” says Wade. “We couldn’t do that, because there are tunnels on the Tennessee- Tombigbee River, and not enough depth. The State Port Authority over a year ago started working on an alternative – on an island at the mouth of the docks, they would purchase property, build a dock where the ships would come up, offload steel onto barges, and the barges would go up the river to the site. Once that was worked out to the satisfaction of the company, at least we had solved the problem with a one- step process, and that kept us in the ballgame.”

“If there’s one thing that separated us somewhat,” says Gov. Riley, “it was our ability to take any problems they had and come up with a solution they understood and agreed with.”

Another facet helping the business case involved a special brand of Alabama coking coal which can be shipped back to Brazil on the ships that bring the steel slabs from ThyssenKrupp’s new plant in Sepetiba, rather than forcing them to deadhead back to South America.

Referring to the original search area that encompassed much of the eastern U.S. inland waterway system, Hess says, “certain states in the north from a structural cost perspective wouldn’t make sense long term. The client had other ideas about where manufacturing is going to be. And the inbound slab component pulls the plant to the south, if you will, and minimizes inbound transportation cost.”

Hess says manufacturing work force flexibility came up repeatedly too. Mace says their firm met with several heavy manufacturing companies, and once the finalists were announced, ThyssenKrupp teams held multiple working sessions with rail, logistics and utility providers, as well as with other companies already in the areas. Hess says some of the meetings “weren’t only about what was being said. We were looking at who will be the best partners, who will have the best aftercare.”

“Alabama in the last week or so was particularly effective,” says Mace. “I don’t mean financially, but just making sure the partnerships advertised in the courting process were going to be there.”

In early June, TK executives and their families were beginning their personal transitions to Alabama amid plenty of ongoing business transactions and negotiations.

Transport of some of the finished flat steel to the company’s Mexinox operation in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, is also important. Asked how the company will get 340,000 metric tons a year of product there, Woelker says that is still under negotiation.

Waterborne transport is most likely, but rail, he says, is still a possibility.

Wolker says negotiations with the power companies that will supply the 500- megawatt needs of the plant are ongoing. The main power company involved in the attraction of the project was Alabama Power. “The main drivers are electricity and gas for us,” Woelker says. “We are talking to providers about capabilities, rates, mixture of feeding systems like nuclear and coal. Steel is about long stable relationships with utility providers.”

“This plant has a different plant life than an auto plant would,” adds Koenig. “Once you build a complex and sophisticated stainless steel facility, you can’t move it.”

ThyssenKrupp is by no means at rest worldwide. After the Alabama announcement, the company announced the launch of steel blank production at a new plant in Bursa, Turkey, as well as a new steel service center in Poland. Meanwhile, officials in Mobile were approving incentive packages the week after TK’s big news for potential projects from shipyard operator Austal, European consortium EADS and Ohio- based Southeastern Builders and Developers, which wants to build a $9.1- million modular home factory.

Setting up a new home appears to be a southern specialty.

“You will always look at this moment as a defining moment for your company,” pledged Gov. Riley in his onstage comments to ThyssenKrupp executives on May 11, “and will begin to look to this state as ‘Sweet Home Alabama.’ “

t nearly the same time as ThyssenKrupp went public with its site selection finalists in early 2007, Bellevue, Wash.- based heavy- duty truck manufacturer PACCAR Inc. announced it had also entered the final phase of a site selection process for a $400- million engine facility and technology center somewhere in the southeast U.S.

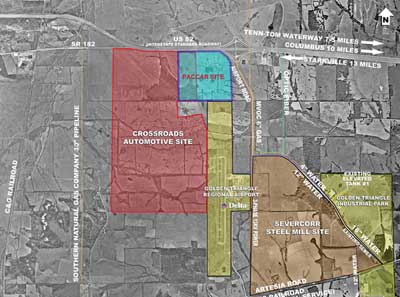

The parallels continued with the company’s choice of May 11 – the very day of ThyssenKrupp’s announcement – to announce its own choice of Columbus, Miss., a town chosen just 18 months earlier by mini- mill operator SeverCorr for a major mill operation. In a release, Mark Pigott, chairman and CEO, said, “PACCAR is pleased to locate its engine facility in one of the most dynamic and progressive areas in the Southeast. The Columbus, Mississippi site provides superb proximity to our dealers, customers and strategic supplier partners.” Company officials lauded the support of the state, Lowndes County and Mississippi State University.

Construction on the 400,000- sq.- ft. (37,160- sq.- m.) facility will begin in mid- 2007 and is due to be completed in 2009. The new facility – beginning with 200 employees but ramping up to 500 – will manufacture 12.9- liter and 9.2- liter diesel engines for Kenworth, Peterbilt and DAF vehicles and complements PACCAR’s engine facility in Eindhoven, Netherlands, which the company refurbished in 2005.

Reached by phone on May 11, Robin Easton, PACCAR’s treasurer, was taciturn. Asked about the chosen site’s size and whether it was the community’s Crossroads megasite, he said the company had not released the acreage number, but that the site was “near an industrial park.” Asked about the timeline of the site selection process, milestones and criteria, he said, “It was a detailed and rigorous process. It began a number of months ago.” The company had “looked at a number of different locations” in a “large number of states. Over time we narrowed the search down.” Who was on the team? “A broad team of executives.”

As for criteria, “multiple factors came into play,” said Easton, including highway access, proximity to suppliers and customers, work force availability and quality of life considerations, “with Columbus being rated high in multiple categories.”

Happy to talk about those categories is Joe Max Higgins, CEO of Columbus Lowndes Development Link. He says his team got started in spring 2006, submitted sites, and “really got cranking” on the project in early fall. “We were also a finalist for Project Tiger and for Project Bear, so we had three high- profile super projects at the same time,” he says.

That was after being in the final handful of candidate sites for the Kia plant that went to West Point, Ga. “Project Bear,” announced shortly after the PACCAR selection, was GE Aviation’s project in Batesville, Miss. Project Bear was still unannounced at press time. For “Jupiter,” Columbus was competing with sites in 11 other states. Higgins says up to 40 sites were under the microscope.

Higgins says the chosen site is a composite affair that uses 200 acres (81 hectares) of the Crossroads megasite. “If anything, it makes us more competitive because we’re going to be building a four- lane road, 16- inch water line, and all of that infrastructure to the site,” he says. “We initially submitted a site and they didn’t like it. They asked if we would subdivide the megasite and we said, ‘Sure.’ We took the 200 acres out of the northeast corner and added 200 acres outside the megasite.” The whole process only involved a total of three landowners, with some of the property already under option.

The PACCAR decision was bitter medicine for Arkansas, whose Jonesboro site was a finalist. Not only had the state been knocked out of the ThyssenKrupp site selection early in 2007, but it had lost out to SeverCorr in 2005 when it chose Columbus over a site in Osceola, Ark. Higgins came to Columbus from an economic development post in Paragould, just down the road from Jonesboro.

“We were down to two locations, Arkansas and Mississippi,” says Jeff Forsythe, a senior consultant with McCallum Sweeney who led the firm’s site selection effort. The Crossroads site is a certified megasite under a program administered by McCallum Sweeney for the Tennessee Valley Authority. “We did a lot of due diligence, and when push came to shove, the company felt like Columbus, Miss., was the best spot. They could have picked either one of them and been successful. It was a tough decision for the company.”

Critical to the project’s attraction was a special legislative session similar to a session that helped produce Mississippi’s winning bid for the Toyota project in Tupelo.

“We were selected as the winner contingent on being able to put together the financing,” says Higgins. “We knew local officials were going to deliver. But it still required the legislature to meet. They had some issues over other legislation that they wanted passed. The discussion started involving ours, and some people wanted to deal with both things. Percy Watson, a representative who is chairman of the Ways and Means committee, is the epitome of a gentleman and savvy. He said, ‘Folks, we’ve got to do this.’ He really chinned the bar. They said okay, and it flew through.”

“It was a monumental day because the company said we didn’t have a deal until that legislation passed,” says Gray Swoope, director of the Mississippi Development Authority.

The Mississippi Legislature approved a state bond package totaling $48.4 million, including $23.9 million for on- site improvements such as roads, site preparation, fire service and water and wastewater extensions; and $24.5 million for off- site infrastructure and training, including road improvements and a training center.

Higgins says that one recent prospect was a 90,000- ton potential customer of SeverCorr, but that SeverCorr’s steel capacity did not enter into the picture for the PACCAR deal. What did help, though, was the fact that SeverCorr’s operation, still under construction, has received some 9,000 job applications.

Also crucial was a visit paid by PACCAR executives to the Center for Automotive Vehicular Systems (CAVS) at Mississippi State University in nearby Starkville, a program funded by the legislature when the state first attracted Nissan.

“CAVS was a very strong asset the state was able to demonstrate to us,” says Forsythe.

“When it came to higher education, Mississippi just slam- dunked,” says Higgins, noting that technical conversations between company executives and CAVS researchers started up almost immediately.

Swoope points out that PACCAR’s major truck brands up to now have contained another company’s engine. “This will now be their own engine, with their own clean- diesel technology, and Columbus will be the center for that technology,” he says. “There will be years of impact, and tie- ins for our university.”

“To pop SeverCorr and then two years later get PACCAR, it tells me it’s damned good to have a megasite,” says Higgins. “It makes all those hours seem worth it. We still have 1,600 acres (526 hectares) left, and 700 acres (283 hectares) adjacent to SeverCorr. We’re not land rich, because we have to exercise our options, but nobody on our team thinks we won’t.”

To say land value has appreciated is an understatement.

“When we first did our first megasite and contacted one of the landowners out there, the chief deputy for county said it appraised for $1,950 an acre,” says Higgins. “That was in early 2004. We’ve had small parcels sell for $100,000 to $150,000 an acre. We just had an appraisal done on some land for $25,000 an acre. The property we have optioned averages around $9,000 an acre.

Such appreciation comes naturally to a community that has welcomed $3.3 billion in deals since June 2003.

“Somebody asked me the other day if it would continue,” says Higgins. “It will as long as everybody remembers what it felt like to lose, we get the resources we need, and we don’t care who gets the credit.”

Higgins gives some credit though to his new state and his new city, where the population is only 3,000 more than that of Paragould but the economic development budget is nearly four times as big. He says in Mississippi, “they talk about economic development, they fund economic development, they set themselves up to win and the Congressional delegation knows what they’re after. It’s just different. And once you get in and see how it works, it’s pretty simple – you could replicate it, if you would just take the time and energy to do it.”

Site Selection Online – The magazine of Corporate Real Estate Strategy and Area Economic Development.

©2007 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and not warranted to be accurate or current.