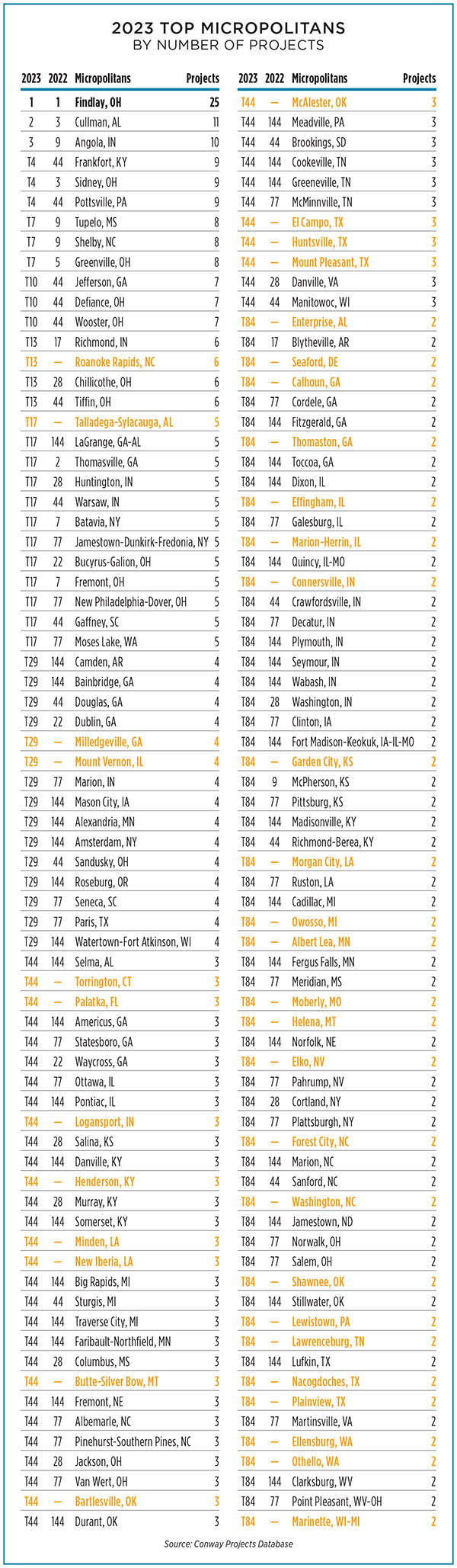

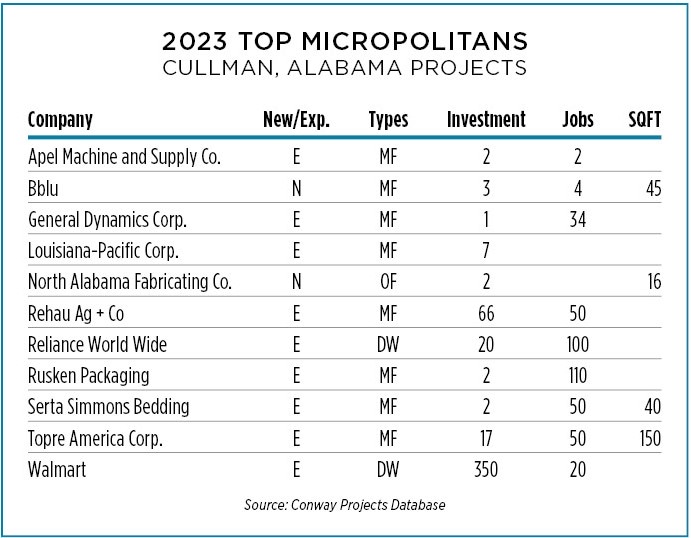

The Findlay decade has come full circle. Findlay, Ohio — a plucky yet muscular manufacturing town of 40,000 on I-75 about 100 miles south of Detroit — is Site Selection’s Top Micropolitan for the 10th straight year. Cullman, Alabama, a consistent Top 5 presence, has risen this year to No. 2, its highest ranking ever. Cullman, halfway between Huntsville and Birmingham in the heart of Alabama’s manufacturing belt, accumulated 11 qualifying investments to Findlay’s typically outsized haul of 25. Highlighted by a $350 million Walmart logistics expansion, the combined value of Cullman’s qualifying investments — $472 million — far eclipsed Findlay’s total of $266 million.

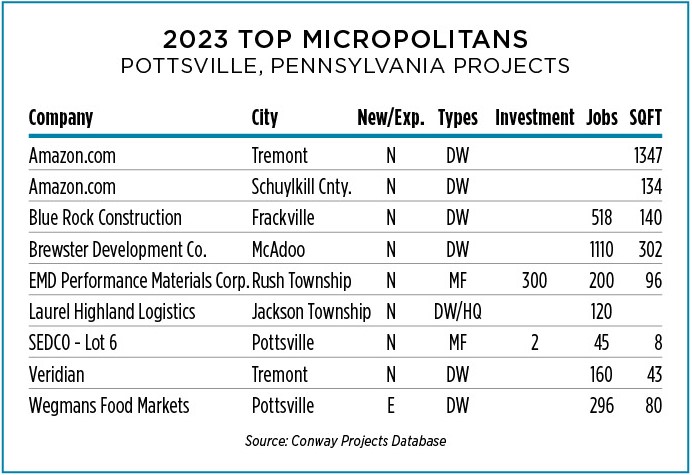

Angola, Indiana, rustled 10 qualifying projects to claim sole third place. Two micros — Frankfort, Kentucky, and Pottsville, Pennsylvania — climbed 40 spots in our ranking to share No. 4 with Sidney, Ohio. All three accumulated nine qualifying investments, with Pottsville snagging another of the top micro investments of the year, a $300 million manufacturing project from German-owned EMD Electronics.

Topping that list by capital investment was Albemarle Corporation’s $350 million investment in a lithium mine in Shelby, North Carolina, one of three micros to tie at No. 7. Tupelo, Mississippi, and Greenville, Ohio, joined Shelby with eight qualifying investments.

Accounting for ties, 12 micropolitans made our Top 10. Jefferson, Georgia; Defiance, Ohio; and Wooster, Ohio, all rose from outside the top 40 into a tie at No. 10. Each had seven qualifying investments.

Photo courtesy of Wayne Economic Development Council

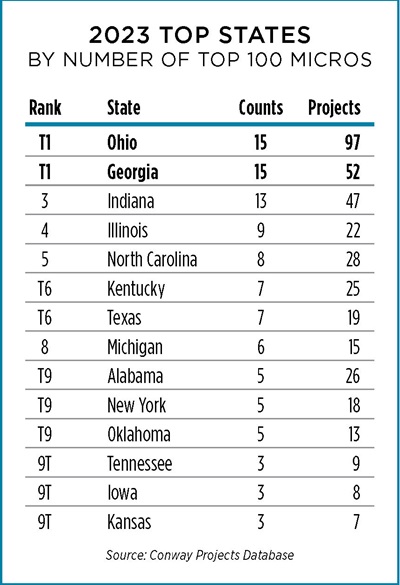

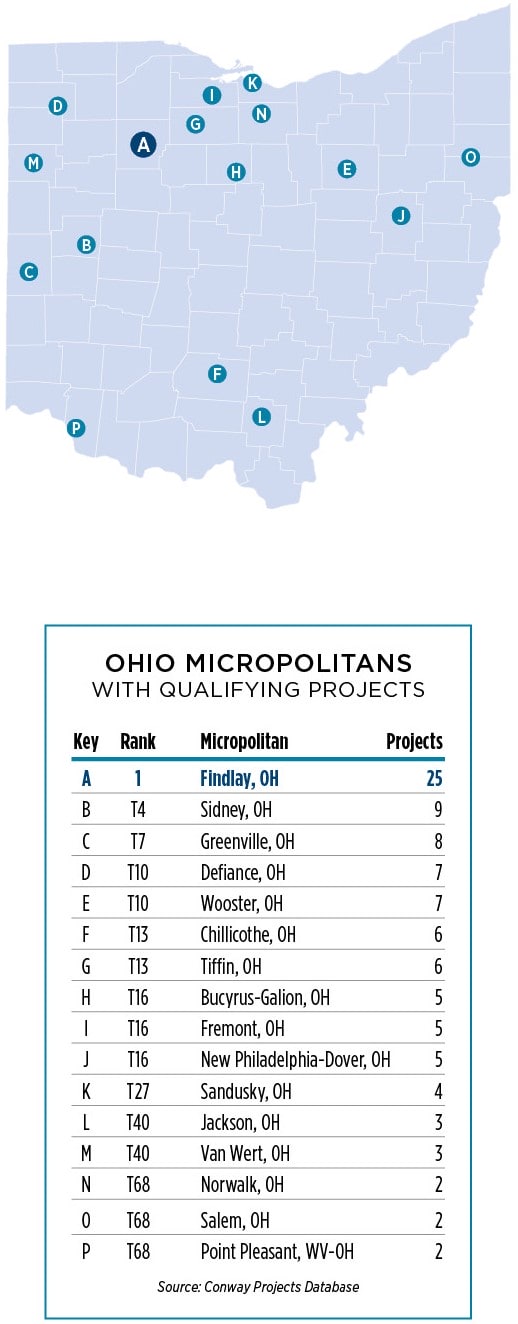

With Findlay leading the way, the state of Ohio likewise dominates our statewide assessment of micropolitans, just as it did last year and the year before that. As demonstrated above, five Ohio micropolitans are among the nation’s Top 10. In all, 15 ranked Ohio micros amassed 97 projects.

Georgia, also with 15 micros earning spots in our ranking, flip-flopped with Indiana for the No. 2 spot with 52 projects. Indiana snared 47. New this year to the Top 10 are Michigan, Alabama, Tennessee, Iowa and Minnesota, while Arkansas, Louisiana, Pennsylvania and South Carolina dropped out.

Speaking of new arrivals: Forty of the 144 micros that make this year’s list of Top 100 and ties were unranked last year, including Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina (tied for No. 13 with six projects) and Talladega-Sylacauga, Alabama (tied for No. 17 with five projects). All 40 are color-coded in orange in the chart below.

In total, the 144 communities making our Top 100 and ties amassed 502 projects.

From the Farm to the Factory

Asked why Ohio so consistently dominates among micropolitans, Dan Sheaffer begins with the simplest of what are several potential explanations.

“I think Ohio is number one,” says Sheaffer, executive director of Findlay-Hancock County Economic Development, “because we make things.

True enough, around half of the qualifying projects in Ohio micropolitans are classified as manufacturing. They include Whirlpool’s latest expansion in Greenville; a $55 million expansion by General Motors in Defiance; and Schaeffler Transmission going in for $30 million on a new plant in Wooster. Wooster also won a $120 million expansion of a Daisy Brand dairy plant.

Sheaffer doesn’t avoid invoking the old Midwest work ethic adage. Neither does Tim Mayle, executive director of the Center to Advance Manufacturing, a joint undertaking of Bowling Green State University, the University of Findlay and Owens Community College.

“It’s not to say that other areas are lazy or don’t have a work ethic,” Mayle begins, “but it’s a real thing that people in the Midwest want to work hard and take great pride in their communities. How people grow up within those communities leads to how they handle themselves at work and to their willingness to work hard and get the job done.

“Manufacturers,” he continues, “want to produce a quality part. They want to do it safely. They want to increase capacity and they want to innovate. All of that requires the kind of individuals we’re talking about.”

Grob Systems, an automotive and aerospace supplier in Hancock County, recruits straight from the farm, says Sheaffer. Headquartered in Germany, Grob is in the midst of expanding to the tune of $18 million and adding 200 new jobs in the village of Bluffton, within the Findlay micro. According to Mayle, Grob hires 40 apprentices recruited from rural school districts every year.

“They recruit there because they like to find individuals who grew up cranking on their cars, the types of kids that are used to working on tractors and farm equipment. They are instinctive problem solvers.”

More Reasons Companies Choose Small Town Ohio

For micropolitan Ohio’s most recent successes, Mayle is quick to credit the leadership of Gov. Mike DeWine — just having begun his second term in office — and the economic team he has assembled. It includes Lt. Gov. Jon Husted and Lydia Mihalik, director of the Ohio Department of Development and a former Findlay mayor. In November, DeWine, Husted and Mihalik jointly announced details of the state’s emerging Innovation Hubs Program, a $125 million project aimed at invigorating small and medium-sized Ohio cities by generating jobs, increasing STEM talent and attracting research funding and capital investment.

“With this program,” said DeWine, “we’re investing in Ohio’s long-term future and enabling the success we’ve seen through our Innovation Districts in Columbus, Cincinnati and Cleveland to be realized across the state.”

Photo Courtesy of Findlay-Hancock County Alliance

Ohio, says Mayle, also is redoubling efforts at the state level to invest in its smaller cities through tax credits that support the types of physical improvements that foster a more vibrant sense of place. More broadly, he believes Ohio’s smaller towns benefit from Ohio’s statewide momentum, as reflected in megaprojects announced by Intel, Ford Motor Company and Abbott Labs.

“Not only does Ohio now have five of the Top 10 micropolitans,” he says, “but it’s landed some of the biggest deals in the country. So, what is it? I’d say it’s a business-friendly environment and good, stable political leadership.”

Stability may account in large part for so many companies that operate in Ohio choosing to expand there rather than to seek greener pastures elsewhere. Expansions in 2023 accounted for about three-quarters of qualifying projects among Ohio micropolitans.

Perennially boosted by repeat investors that include such luminaries as Whirlpool, Marathon Petroleum and Cooper Tires, Findlay managed to notch nine new projects — against 14 expansions — in 2023, including its biggest. Sheetz, Inc., the convenience store operator that’s expanding from the East Coast into the Midwest, is building a $150 million food production facility that’s to create 200 new jobs. For Sheaffer, that’s reason enough to continue to play what he calls “the long game” of recruitment, even as retaining and helping to grow existing businesses offers far better odds of success.

“Man,” he says, “it takes 24 to 36 months to land a new company, and you’re in competition with three or four states and 25 locations, which means you lose almost every game. But,” he says, “you’ve got to suit up and get in there.”

That relentless approach has produced — during the decade of Findlay — 291 projects, $2.1 billion of capital investment, some 5 million sq. ft. constructed and close to 12,000 jobs created in a town of fewer than 50,000 people. Findlay is literally playing out of its league: Its 25 qualifying projects for 2023 would have earned it Site Selection’s No.1 ranking among Tier 3 metros, the next class up. Truly amazing that, as if the nearby Toledo Mud Hens were to win the World Series.

Cullman, Alabama, Automates Its Future

Findlay’s enduring dominance has become well known within economic development circles across Micropolitan America.

“Every year we play for second,” says Dale Greer, director of the Cullman Economic Development Agency (CEDA), of Site Selection’s ranking.

For Cullman, then, it’s mission accomplished. And with an exclamation point, as our No. 2 micropolitan — in addition to landing its highest ranking among Top Micropolitans— recorded its biggest ever investment in 2023. A Walmart distribution center, in the community for a good 40 years, is automating to the tune of $350 million.

“They came in ’82 or ’83,” says Greer, “one of the first tenants in our industrial park that helped start us down this road.”

Today, says Greer, the Walmart DC has grown to 1.3 million sq. ft. with a headcount of over 1,000 employees. The four-year rollout of robotics is not expected to dent employment at the facility, says Greer, given the expected, continued growth of the retailer’s surrounding footprint and the company’s plans to train team members for automation. And the $350 million upgrade, Greer believes, signals Walmart isn’t going anywhere. Its Cullman DC currently serves markets in northern Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi and Georgia.

“An investment of that size,” he says, “you figure you’ve got them at least another 20 or 30 years.”

Each of Cullman’s 11 qualifying projects for 2023 was an expansion of an existing business. Including smaller investments that didn’t meet Site Selection’s thresholds, Cullman last year did just under $489 million in capital investment with 643 jobs created, according to Stanley Kennedy, CEDA project manager. That’s quite a lot, Kennedy notes, for a town of 20,000 people, or half the size of Findlay.

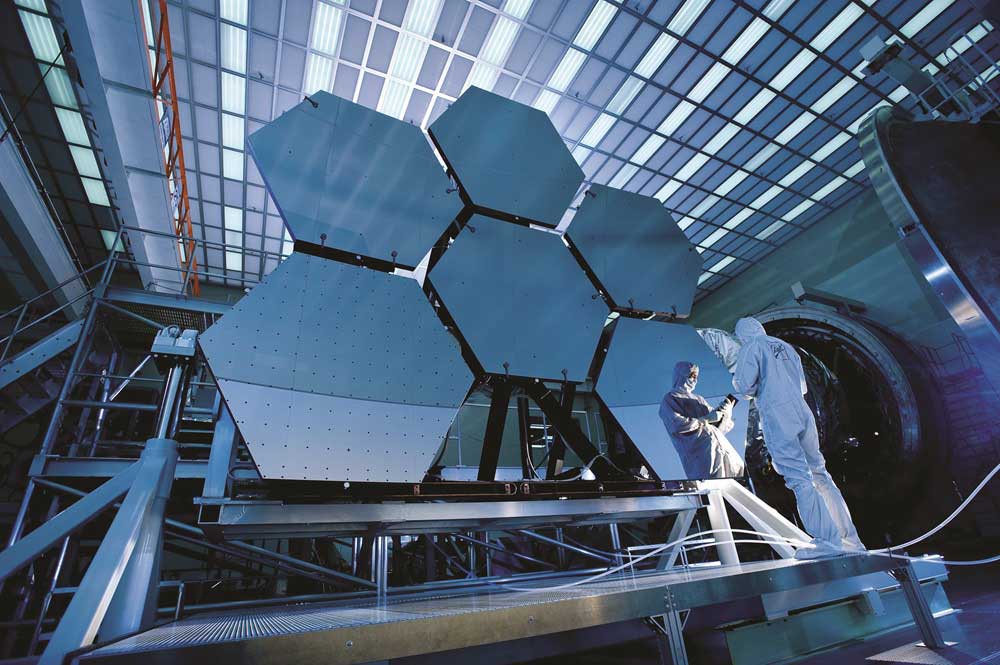

That small town is delivering on some outsized work. General Dynamics Global Imaging Technologies, in Cullman since 2004, is yet another demonstration of how products of mind-boggling complexity can emerge from unexpected places. The aerospace contractor’s Cullman facility played a key role in the design of the James Webb Telescope, which has changed astronomers’ understanding of the beginnings of the universe since its launch on Christmas Day, 2001. The Cullman team provided the 18 hexagonal segments that comprise the Webb’s primary mirror system. Each mirror segment, 1.32 meters in diameter and covered in a microscopically thin layer of gold, required machining so precise as to require some 8,000 separate measurements.

“They do tolerances into the millions,” says Greer, who calls General Dynamics one of Cullman’s “premier employers.” The facility is hiring close to three dozen more employees and mulling yet another expansion.

While aerospace is clearly a natural for a town less than 45 minutes south of Huntsville — America’s “Rocket City” — the rocket fuel that has launched Cullman to new heights is the burgeoning automotive industry in Alabama and surrounding states.

“The growth of automotive,” says Greer, “has contributed a ton to Cullman being ranked so highly” among Site Selection’s Top Micropolitans. Cullman, says Greer, now is home to three Tier 1 automotive suppliers and a dozen smaller ones that, combined, employ in the thousands.

Topre America, the U.S. subsidiary of Japan’s Topre Corporation, came to Cullman in 2003. Topre is a metal stamping parts supplier for Nissan, Toyota and Honda, all of which are growing in the Southeast. The Cullman location now serves as Topre’s North America headquarters. Last year, Topre announced what is at least its sixth expansion, a $17 million investment that’s to create 50 new jobs and 150,000 sq. ft. of additional manufacturing space.

Photo courtesy of Cullman Economic Development Agency

Another supplier, Germany’s Rehau, is expanding in Cullman to the tune of $66 million and 50 new workers as well. Rehau came to Cullman in 1996, the year of Mercedes’ monumental decision to produce vehicles outside of Tuscaloosa, about an hour south of Cullman. Among other projects, Rehau makes bumpers for Mercedes’ new generation of electric vehicles.

“When Rehau came in, they said they would never be bigger than 40,000 square feet or 50 employees,” says Greer. “Now they have a million square feet under roof and about 675 employees, and we think we’re guaranteed to have them for at least another 20 to 25 years, too.”

Photo From webb.nasa.gov

For their workforce needs, these Cullman manufacturers draw heavily upon Wallace State Community College in nearby Hanceville. Led by long-time President Vicki Karolewics, Wallace State has been instrumental in establishing regional workforce training centers and other business development initiatives. Zero RPM, a technology business hatched in Cullman, was incubated at Wallace State before finding permanent space, its current facility one of a growing cadre of R&D centers that are sprouting up around Cullman. Another is DB Technologies, which does research, Greer says, for NASA and Lamborghini.

“This is the direction we’re moving in,” he says.

It’s a strategy that gels not only with Cullman’s evolving expertise in aerospace, automotive and automation, but also reckons with an unemployment rate of 2%, about the lowest in the state.

“These R&D projects,” he says, “require fewer workers. Fewer workers and better pay. Some are six-figure salaries. That’s what we’re focusing on.”

Photo courtesy of EMD Electronics

Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Time to Shine?

A little under two hours northeast of Philadelphia, the town of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, is one of the highest risers among our Top Micropolitans, having climbed from No. 44 in last year’s ranking all the way into a tie at No. 4. Like Cullman, Pottsville inked a generational deal in 2023 — a $300 million investment in specialty gases manufacturing for the semiconductor industry by EMD Electronics, a division of Merck KGaA of Darmstadt, Germany. Billed as the largest facility of its kind in the world, the planned 96,500-sq.-ft. plant is to employ 200 workers.

Potentially game-changing as it is, the EMD investment is an outlier among Pottsville’s nine qualifying projects, seven of which are distribution centers. Logistics has emerged as Pottsville’s bread and butter, and that of surrounding Schuylkill County.

“During the year after COVID, we did more industrial warehouse distribution development than we did in the previous 10 years,” says John Augustine III, president and CEO of Penn’s Northeast, the region’s economic development agency. “As fast as we can put up a spec building,” Augustine says, “it’s taken off the market.”

The COVID effect, Augustine believes, has fundamentally altered corporate delivery strategies and individual habits in ways that account for the explosion he has witnessed.

“During COVID,” he explains, “everybody saw the supply chain was broken. Companies that had product idling offshore on ships decided they would rather have that product stored here in a warehouse than be stuck in China or out in the ocean.”

And then, says Augustine, there was the concurrent explosion of e-commerce.

“What COVID did that a lot of people don’t fully appreciate,” he believes, “is it took the Baby Boomer generation and forced them into online shopping exclusively. My parents, who are in their late 60s, had no other choice than to do what my generation and my kids’ generation already were doing already. While some of them are returning to brick-and-mortar, they’re still shopping online.”

Interstate 81, says Augustine, numbers 10 interchanges as it rolls through Schuylkill County. Seven of the 10, he says, have active speculative warehouse development in excess of 8 million sq. ft.

“That’s why you see us jumping in the rankings,” he says. “It’s an e-commerce world. We’re seeing developers from all over who want to get in.”

Forces that are even bigger still — namely, geography and economic migration —may be coalescing in Pottsville’s favor, too.

“Traditionally,” says Augustine, “development moves inward from the ports. In our case, Philadelphia and New York fill up and become more expensive. So, you go west to the Lehigh Valley, but now a good portion of the projects we’re doing is spillover from there. So, for us,” he says “it’s that moving inwards and having that available workforce. What you’re seeing is that it’s our time to shine.”