If there’s one perennial challenge for corporate real estate directors at global multinationals, it’s asset disposition — the unloading of surplus properties still in a company’s portfolio despite being shut down, sometimes for decades.

So why has it taken until now for the first global surplus property management benchmark report?

Design, engineering and project management consultancy Arcadis in October released the 2017 Global Surplus Property Disposal Benchmarking Report, based on a grand total of 33 respondents across several industry verticals, with large multinational portfolios.

That may not sound like a lot, but the questions posed are not questions every company feels comfortable answering — “What’s your environmental liability reserve?” “Where are your surplus properties around the world, and how much do they cost you annually?” In that context, accumulating input from a group of companies with a combined gross revenue of $1.5 trillion and approximately $2 billion in surplus property holdings in 2016 is an accomplishment.

Mark Fenner, senior vice president at Arcadis, says most of those holdings are in the US, the UK and continental Europe, owing in part to those regions’ established industry and the laws and regulations governing it. The Middle East and Asia? Not so much, he says. And not just because the areas are pro business. “There are lots of environmental regulations in Asia,” he observes, but as with some intellectual property issues, “very little enforcement to date.”

To assure a meaningful sample, Fenner says survey respondents were promised anonymity, as well as a customized report and meeting to go over each respondent’s results as they compare to overall findings. Among the key highlights:

- Thirty-five percent of the responding companies have no formal plan for surplus property disposal, “resulting in missed opportunities for reducing business risks such as financial, environmental, legal and reputational factors.”

- Eighty-one percent do not prioritize surplus property disposal at an executive level.

- Most firms’ surplus property portfolios are relatively small, with 83 percent of respondents indicating they hold fewer than 200 such properties globally and 60 percent reporting less than 50. “These assets are diverse in nature,” said Arcadis, “ranging from very small parcels to massive manufacturing complexes and from properties in high-value locations (i.e., near major transportation corridors, urban areas, ports, etc.) to more challenging markets in isolated, rural areas. Small portfolio size often leads to easier management and a faster track to a divestment opportunity.”

- Fifty-four percent spend more than $5 million annually in carrying costs — including compliance, permits, licenses, taxes, utilities, security and site maintenance — to hold onto surplus industrial sites.

- More than half held less than $25 million in total environmental liability for cleanup of their surplus properties, and 82 percent said environmental cleanup was concentrated on only a few properties. “While most companies perceive remediation as a barrier, progressive firms are successfully selling contaminated surplus properties with few legal or financial hurdles.”

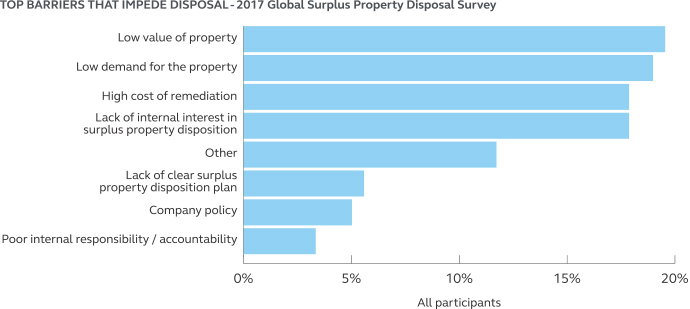

- Internal company barriers impede disposal. “Our study finds 32 percent of respondents believe that non-economic factors like poor disposal planning, lack of interest, and restrictive company policies can prevent them from disposing of surplus property.”

“With the industrial real estate market booming in western economies and the availability of property diminishing, now is an excellent time to take advantage of disposing of surplus property,” said Fenner in October, especially as the e-commerce boom drives demand for “last mile” fulfillment locations close to big populations, i.e. in old commercial/industrial zones. “By planning strategically, corporations realize major benefits such as higher profits, an optimized asset portfolio, reduced liabilities, healthier balance sheets and an improved public image.”

In an interview from the Amsterdam-based company’s US base in metro Denver, Colorado, Fenner says the idea for the survey arose from environmental and corporate real estate professionals at around 25 multinational companies who in 2013 formed a group called the Surplus Property Roundtable. Because so many of the firms involved in the roundtable were Arcadis clients, Fenner’s team performed an informal survey just for them that was met with strong positive feedback.

“It was exactly the kind of information they were seeking,” Fenner says. “I said, ‘Boy, we deal with an awful lot of companies that would be interested.’ ”

Still Not On the Agenda

Ah yes, being interested. If there’s a No. 2 perennial complaint among corporate real estate (CRE) professionals after asset disposition, it’s the c-suite’s disposition toward corporate real estate in general, best described by what it’s not: not top of mind, not a priority, with no proverbial seat at the table. The average dormancy of surplus properties among survey respondents’ companies was 18-20 years — a stunningly long time to most of us, but no surprise to CRE departments.

“One reason these properties sit for so long is it’s not [a priority] at the c-suite level,” Fenner says, “so therefore there hasn’t been a lot of action. And they continue to add more and more properties all the time,” especially following the global financial crisis and then a strong spike in M&A activity in 2015. Companies continue to shoulder carrying costs such as taxes and keep spending on environmental cleanup, but don’t seem overly concerned about removing eyesores from their books or from the neighborhoods they inhabit.

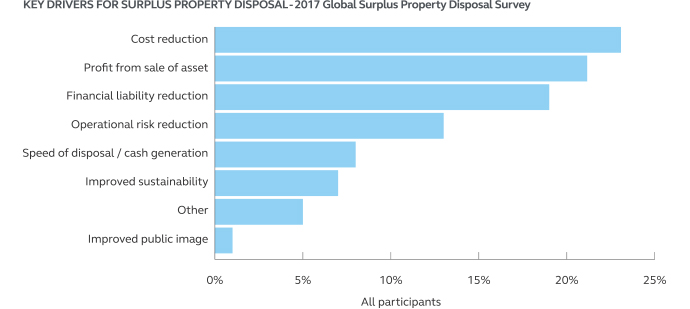

“Motivations such as improving public image and sustainability were really low drivers,” Fenner says. “I was surprised. I thought sustainability would be higher. But we didn’t see that. It’s not top of mind for companies to improve public image and sustainability.”

A quarter of respondents reported redundant property disposal was not a management priority at all. From the developer and community point of view, however, you can’t turn around without running into a new transit-oriented, mixed-use development rising from the ashes of an industrial eyesore. Everyone knows behemoths move slowly, but how are they missing this opportunity?

“I don’t think it’s part of their agenda,” says Fenner. “For mixed use and other transformations of properties, most of it is being driven by local developers capitalizing on favorable market conditions. They’re the ones reaching out, saying, ‘We see an opportunity for transit-oriented development, and you have this industrial property.’ As opposed to a company saying, ‘Here are high-value areas where we have surplus properties. Let’s put a team together to figure out how to get them off of our books.’ A third of these companies don’t have disposal plans. Some don’t even have inventories,” in part because of decentralized operations.

With so much major transportation infrastructure work on its docket as well as its enterprise-level clientele, does Arcadis come across opportunities to bring those two sets of clients together to turn a surplus property into a linchpin for a transport infrastructure site?

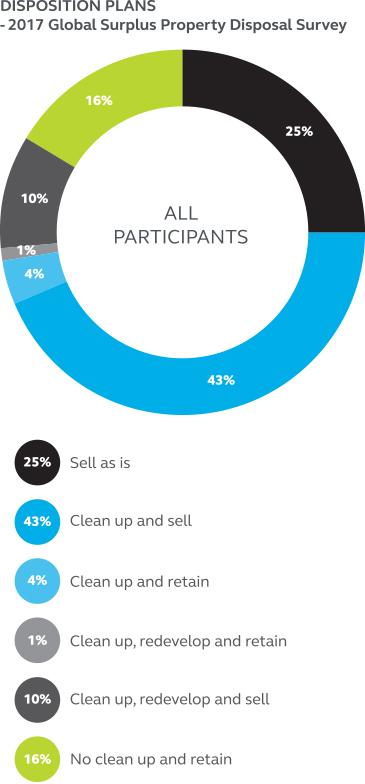

“Yes, we’re trying to do more of that,” Fenner says. “But that’s usually driven by a developer or municipality identifying the transit-oriented development [TOD], as opposed to an industrial client.” Moreover, the survey found only 11 percent of respondents are investing in redevelopment of their own surplus properties. “They just want to get it off their books,” says Fenner. “They don’t see it as a business proposition.”

Centralizing authority could be one way to prioritize CRE and surplus property challenges at the same time. The organizational groundwork is already in place: The Arcadis research found that 83 percent of respondents placed the responsibility for property disposal at an enterprise level. More specifically, 62 percent said they directed their corporate real estate departments to manage surplus property disposal. Fenner says the other 21 percent of firms tend to delegate it to the environmental team. “This means 17 percent are still delegating responsibility to individual operating business units,” the report stated, “which is less efficient and reduces the ability to sell a large portfolio of properties simultaneously.”

Fenner says his team sees best performance in this arena when a company has designated a person as responsible and accountable, and also given that person has the authority to dispose of surplus properties.

“It’s not uncommon for CRE to have responsibility, but they don’t really necessarily have the full authority,” he says, in part because of the environmental checklist. For those firms that have centralized, “no question those companies are the ones moving surplus properties. Or they might say, ‘We need to reposition, spend money on cleanup and demolish buildings.”

Go with Your First Counterintuitive Gut Feeling

Two recommendations from the Arcadis team sound odd at first, but make perfect sense the more you think about them.

The first: Adopt a portfolio strategy. “Selling surplus properties one by one is slow and costly. In contrast, the transaction cost of a portfolio is relatively inexpensive and owners can bundle low-value properties with higher valued assets.” More than 90 percent of the 33 respondents reported selling surplus properties individually rather than as a portfolio, which increases average transactional costs.

The report offers the example of a portfolio of gas stations. But isn’t it a lot easier to bundle gas stations than to bundle other types of properties?

“It’s more difficult to sell portfolios,” Fenner admits, but those who find a way to do it “are just smart, frankly,” he says. “That’s because when you sell individual properties, you sell the ones most economically attractive and easiest to sell. At the end of the day, you’ve sold your higher-value properties, and you’re left with a lot of dogs. The companies we’ve worked with that are more progressive bundle a few high-value properties with low-value properties into a portfolio and say, ‘This is the package. If you want these coastline attractive properties near nice transit hubs, they’re for sale, but you have to take these other properties that come with it.’ That’s the benefit of selling in a portfolio.”

Likely buyers can be national developers, large financial institutions and private equity firms.

Apparently those buyers are okay with another recommendation from Arcadis: Sell environmentally contaminated property and allow buyers to remediate. But isn’t that a bit off-putting to the prospective purchaser? Not necessarily. “Current environmental regulations are known factors with few new regulations being imposed,” the report says, “and the rate of returning environmental liabilities to the sellers is low.”

“If you look at all the major environmental legislation,” explains Fenner, “it was passed in the late ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, with very little in the 2000s. Most have been in place for decades. Whereas before the remediation was a mystery and a black box, and people were concerned about the liability, now there is enough empirical data to quantify the risk. And there is harmonizing of competency in the field,” he adds, with environmental consultants on staff for companies and a deepening well of experience working with regulators from every state. “The pool of knowledge is so much better. And you can also quantify the comeback liability.” In the past, corporate types have been concerned they’d sell to a developer or company and if they didn’t perform properly, it would come back to the sellers because they had the deep pockets.

“Now we can provide evidence that the comeback liability is quite small,” Fenner says. “And when it does come back, the economic requirements are quite small, particularly in relation to the gains they get.”