E-commerce is exploding in Asia and dwarfs the North American market. China alone accounts for over 40 percent of global e-commerce transactions. On Singles Day in 2016 (11/11, when China’s singles celebrate their singleness), Alibaba transacted US$17.5 billion in sales compared to about US$6.9 billion for Black Friday and Cyber Monday combined. The Singles Day sales total grew to $25 billion a year later.

China is home to 730 million Internet users, and its mobile payments market is over 11 times the size of the market in the US. As e-commerce and digital transactions expand exponentially, data centers, the warehouses of the digital revolution, are being built at a breakneck pace in China, just like they are in the US.

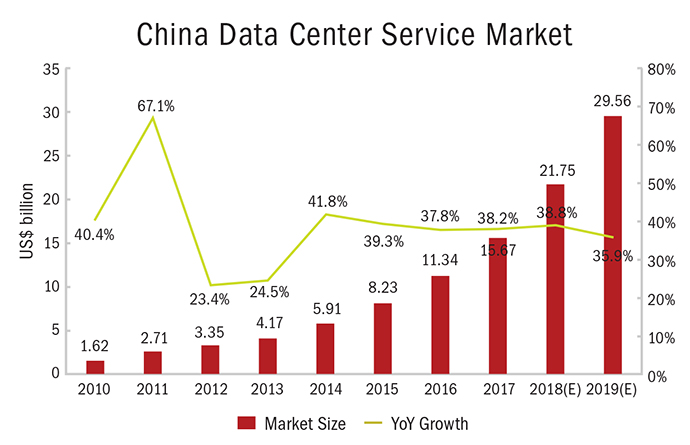

China’s data center services market has grown significantly over the past decade, with the value of services provided growing at a CAGR of 38 percent from 2010 to 2017. In 2017, the market approached US$15.9 billion, and is projected to continue growing steadily in the coming years.

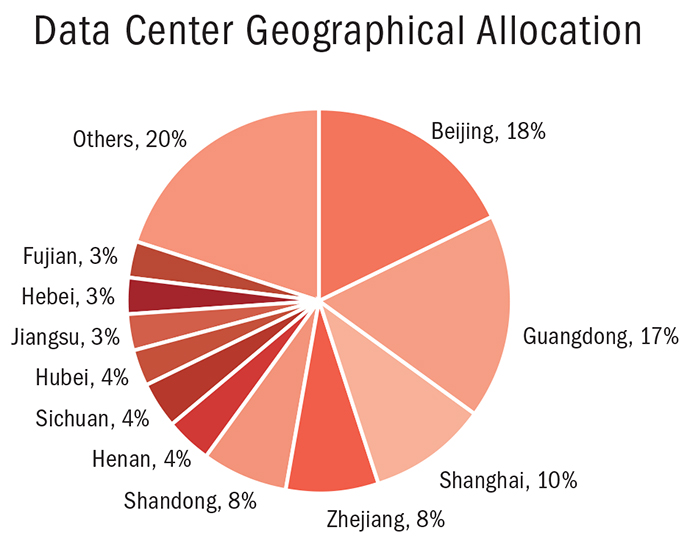

Currently, China’s data center market is still largely made up of small- to medium-scale data centers (those hosting less than 3,000 servers), located around China’s Tier-1 cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.

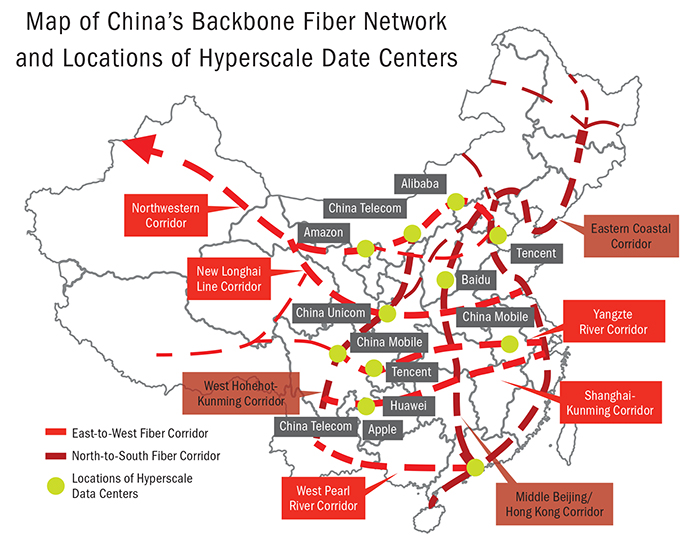

However, rising market demand has driven industry leaders, both state-owned and private companies, to build hyper-scale data centers. While small- to medium-scale data centers are predominantly located along the developed East Coast, hyper-scale centers are being located in northern and southwestern China.

Location Trends

Hyper-scale data centers require large sites and consume power at incredible rates (a 100,000-server center requires about 50-60 MW of electricity, equivalent to the output of 500,000-600,000 sq. m. [5.4 million to 6.5 million sq. ft.] of solar panels). In China the cost of real estate and electricity and access to backbone fiber networks are the principal site location considerations, while the larger issue of data security lurks. From a broader location strategy perspective, compliance with China’s cybersecurity laws, which many companies consider too intrusive, is the principal consideration most multinationals have in considering China as a location for storing sensitive data.

In 2015, Alibaba invested US$2.86 billion to build its hyper-scale data center in Zhangbei County, a small agricultural town at the northwestern corner of Hebei Province, near the southern rim of the Inner Mongolia Plateau. The data center now hosts 300,000 servers with expandable capacity to 600,000. Alibaba selected Zhangbei for its abundance of cheap land, renewable energy (solar and wind power stations already in place), cold climate (annual average temperature 3.2°C), access to China’s national Northwestern Fiber Corridor and proximity to Beijing (its largest market in northern China).

Guizhou Province is also a popular location for hyper-scale data centers. Gui’an New District is a national-level Economic Development Zone (EDZ) that positions itself as an attractive data center location. The zone is one of many that has specific incentives to attract data center providers focused on facility, electricity and talent acquisition costs.

The Gui’an New District in Guizhou Province in South-Central China is connected to the Shanghai-Kunming Fiber Corridor. It has already attracted all three state-owned telecom operators and private market leaders such as Huawei, Tencent and Foxconn to establish their data centers. In 2013, China Telecom made a US$1.12-billion investment to set-up a 340,000-sq.-m. (3.6-million-sq.-ft.) hyper-scale data center to house 800,000 servers. Much like Google following Apple into the Reno, Nevada, area, Huawei China Telecom in 2016 started building a 400,000-sq.-m. (4.3-million-sq.-ft.) facility with 600,000 servers. Apple announced in July 2017 that it will invest US$1 billion to set up its first data center in China, also in Gui’an New District, to comply with China’s new Cybersecurity Law that came into effect in June 2017.

Regulatory Impacts on Foreign Data Center Operations in China

The Cybersecurity Law, Presidential Decree No. 53, defines data center businesses broadly as “network operators” who are responsible for the protection of personal and other critical information or data collected or generated in China, and stored domestically. The law makes transferring this data out of the country difficult for foreign companies operating in China, creating, as in many other jurisdictions, significant local demand for data centers.

According to the Regulations for Foreign Invested Telecom Enterprises, State Council Decree No. 666 [2016], foreign enterprises may not hold more than 50 percent of the equity in data center operations. This regulation has not halted global data service providers from entering the China market. IBM, Microsoft, KDDI, Amazon and Equinix have all entered the market through local partnerships. In 2016, Amazon established its 10th global data center in the northern Chinese province of Ningxia — an area the Chinese government is also promoting as a wine region. Taking advantage of the cool climate, subsidized land and ample supply of renewable energy, Amazon partnered with a local player to set up a hyper-scale data center in a 300,000-sq.-m. (3.2 million-sq.-ft.) facility housing 400,000 servers.

As one of the top economic priorities of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, the country is making a concerted effort to develop and promote applications such as big data, cloud-computing and IoT applications, leading to increasing demand for hyper-scale data centers. Under the current regulatory environment, local companies will continue to dominate the market. Because of the foreign equity limitation, foreign data center operators have additional criteria to consider in their location decision-making. In addition to typical site location criteria, a company must determine who to partner with for the investment — another critical commercial decision that requires a systematic and objective process based on well-defined criteria and well researched data. Like site location decisions, joint venture partner decisions are irrevocable and require informed counsel with proven in-market experience. Making either the wrong location or partner decision can be commercially disastrous.

American operators may face additional challenges due to reciprocal tariffs and restrictions in reaction to the trade tariffs President Trump announced on March 22, which would level tariffs on up to $60 billion worth of Chinese imports into the US. The day after Mr. Trump announced the new tariffs, China announced retaliatory tariffs upwards of $3 billion worth of US exports including many food products and aluminum and steel pipes. This follows an already increased scrutiny on Chinese investments into the US under the Trump administration. The full extent of how China will reciprocate is yet to be determined, and the effect it will have on American data center JV investments is uncertain.

Wan Yao is a Senior Research Analyst and Kirsten Olson is a Consultant in the Shanghai office and Dennis J. Meseroll is a Co-Founder and Executive Director of Tractus Asia, based in the Bangkok office. With offices in Shanghai, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Singapore, Jakarta, Yangon, Chennai and New Delhi, Tractus Asia is a foreign direct investment strategy firm dedicated to assisting its clients in making informed decisions about where to locate their investments and how to effectively structure and execute their market entry and business strategies in Asia. For more, visit www.tractus-asia.com.