![]()

ccording to Ralph Nader’s group League of Fans, 12 total Major League Baseball teams, nine NFL teams, eight NBA franchises and six NHL teams are currently involved in arena deals. All in all, some $2 billion a year in public money goes toward pro sports facility construction, from scores of minor league baseball parks like the new one going up in Gwinnett County, Ga., for the Triple-A Atlanta Braves franchise just next door, to the $1.3-billion new stadium for the New York Yankees.

A recent study of pro sports facilities in the U.S. by Prof. Paul Anderson, associate director of the National Sports Law Institute at Marquette University Law School, found that 78 percent of current teams are in facilities that are new or have been renovated since 1990. The average cost for a stadium is now around $400 million, with arenas going for $250 million.

Deals to develop them are indicators that a community has incentives and is willing to wield them, and coliseums through the ages have helped build community spirit through sports as an entertainment amenity. On the other hand, they’re for sports, which some might say is not a productive niche deserving of public money. Wouldn’t corporate leaders and their consultants prefer to see those communities spending that money on infrastructure, education or other corporate projects?

Not necessarily.

“The development of sports complexes of any type with various types of tax subsidies and incentives are true economic development programs that enhance the job growth, economic values, and overall qualities of locations,” says Mike Mullis, founder of esteemed site selection firm J.M. Mullis, Inc., based in Memphis, Tenn., where downtown’s centerpiece is the gleaming home of Triple-A St. Louis Cardinal affiliate the Memphis Redbirds.

“Public subsidy for stadium construction does not materially affect corporate site selection,” says Daniel Levine, executive director, Location & Incentive Services, for ADP, based in East Brunswick N.J. “Corporate relocation is almost always driven by a desire to reduce costs; attract or retain labor; better serve markets; or manage risk. The presence of a major league sports team can affect one’s assessment of overall quality of life in the community, but certainly by not as much as quality of neighborhoods, schools, congestion, etc.”

Bettina Damiani, Director of Good Jobs New York, is the primary author of “Insider Baseball: How Current and Former Public Officials Pitched a Community Shutout for the New York Yankees,” which reports inconsistencies in job creation projections and property tax assessments associated with the Yankees project, as well as the loss of parkland for parking. She has called the deal “economic development on steroids: plenty of bravado but void of benefit for New Yorkers.” In an interview, she says, “The Yankees deal is where all the eyes are, for the worse, in terms of a new standard in how these things are done.”

Incentives for stadiums and incentives for corporate facility projects are often lumped together by the general public. Asked if she sees differences between the two, Damiani identifies the clear difference between an entertainment venue and a place of daily employment.

“Depending on what the manufacturing and industrial projects are, we sometimes wouldn’t approve of subsidies for them either,” she says, “but at least we’d have more information about jobs.”

She says her organization’s complaints are often met with the retort, “Why are you complaining? It’s federal dollars.” To that she says something that many corporate onlookers might agree with: “We’d rather have federal tax dollars go towards public transportation and infrastructure.”

Sometimes the infrastructure is in the way. Such was the case in Reno, Nev., where a new Triple-A baseball stadium for Arizona Diamondbacks affiliate the Reno Aces next year will be home to rally caps instead of railcars. That’s because, as part of the stadium deal, the city paid some $300 million to relocate Union Pacific tracks into an underground channel. Was it worth it? Time will tell. But already the rejuvenation of a downtown district is inarguable.

Neil deMause, co-author of what some call the “definitive stadium boondoggle guide” Field of Schemes, says, “Compared to manufacturing plants, in terms of deals and subsidies, I think sports teams try to play off the same sort of economic development incentives that have been going on in local government for 30 years, but they’ve taken it to another level.”

He says one reason is pure PR value – sports are hot, manufacturing isn’t. The other factor, he says, is supply and demand.

“There is a limited supply of teams. With a factory, a government can say there are other factories out there. But there aren’t necessarily other football or baseball teams. Put those two factors together, and they can create leverage to get $500- or $600-million deals. At least manufacturing facilities tend to be high labor intensity. A baseball stadium employs 25 guys and a bunch of hot dog salesmen.”

In fact, he says, the cost per job created in sports deals is between $150,000 and $250,000. “If you were a car company, that would be scandalous, but for sports franchises, that seems okay.”

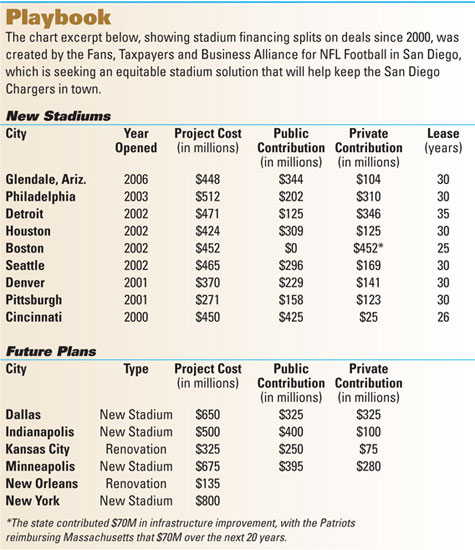

He says the stadium and arena game now has its own playbook – when and how you threaten to leave town, how to work the legislature for tax breaks, and yes, when to ask for another new stadium. The Seattle SuperSonics franchise moved to Oklahoma City earlier this year in part because their arena had not been renovated since 1994. In St. Louis, the NFL’s Rams got a new stadium in 1996, but are already talking about a new one.

Ten years ago, deMause asked University of Michigan sports economist Rodney Fort what was reasonable in terms of stadium shelf life – 30 years, 40 years?

“He said, ‘Every year, if someone else is paying for it,’ says deMause. “It’s true. The only thing keeping them from asking for new stadiums more often is that there’s a limit to chutzpah. You can always make money with a newer building.”

Supporting arguments for sports venues often tout the retail spinoff, but reality can be far less convincing.

“Sports is supposedly a great retail anchor, but the time is so compressed with so many people moving through the area, it’s hard,” observes deMause. “In D.C. [for the new stadium for the Nationals], there was a debate about whether to upgrade a metro station, and somebody from the city made the argument that ‘We’re not going to be able to move through 50,000 people, but that’s good, because we’ll have people milling about.’ Hey, great, a lot of angry, drunken people to feed.”

But there are shining examples. Marquette’s Anderson, in a presentation this summer, pointed to Coors Field, home of the Colorado Rockies. Built in 1995, the facility’s immediate impact was measured in a 70-percent growth in restaurants, five new brewpubs and a residential marketplace in the surrounding area that went from 270 units to 700 units.

But ADP’s Levine makes another point from a design perspective: “Most new stadium and arena facilities are designed to provide expanded retail and dining opportunities within the confines of the facility. Consequently, the jury is out as to just how much economic benefit from these new facilities will spill out into in the surrounding neighborhoods.”

Nevertheless, not all deals are downers for the communities that make them. Nashville built both a hockey arena and a football stadium on spec, before getting the Predators and the Titans. But their agreement with the Predators carries a hefty penalty if the team tries to relocate. According to deMause, some soccer stadium deals are making sure the cities get a revenue cut. He says research by Prof. Judith Grant Long of Rutgers University opened his eyes to the fact that the Metrodome deal in Minneapolis was “actually a pretty good deal for the public.” And Key Arena in Seattle was too, with the 1990s renovation funded primarily with luxury suite money.

“Of course, the Sonics moved to Oklahoma,” he says. “One of the problems is the better deals wind up being ones that cause teams to immediately demand a new one.”

Overall, then, concludes deMause, “you couldn’t do worse than a sports stadium” when it comes to incentive payback. “It’s going to be very difficult for a sports facility to do even as well as a poor deal for a manufacturing facility.” But every time he thinks the string of bad stadium deals is about to run its course, it starts repeating itself.

How the corporate community views it may have a lot to do with exactly who is paying the piper.

“In D.C., when they were levying a business tax to pay for the stadium, there was some griping,” he says. “But typically these sports team owners own other businesses locally and are major players. So I’d think there would be uncomfortable times on the golf course if other corporate leaders were complaining about the deals sports teams got.”

Site Selection Online – The magazine of Corporate Real Estate Strategy and Area Economic Development.

©2008 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and not warranted to be accurate or current.