When a part of a multinational in one country transfers (i.e. sells) goods, services or know-how to another part in another country, the price charged for these goods or services is called the transfer price. How a firm manages its transfer pricing while maintaining compliance with international and national tax rules has a huge bearing on the company’s total effective tax rate and outright profitability. In conjunction with the recent release of proposed updated guidelines on transfer pricing documentation from the Committee of Fiscal Affairs of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), we present the following analysis from Warren Novis, Molly Minnear and Rowena Ashan at KPMG.

The much-dreaded patent cliff has arrived and has brought with it increased competition, reduced sales and diminishing profits. One unexpected issue pharmaceutical companies may need to consider is the impact of the patent cliff on their transfer pricing policies and, ultimately, their effective tax rate. Transfer pricing policies that were determined for a stable or growing product may have unintended consequences with the dramatic changes that have been brought on by patent expiration. This article evaluates the transfer pricing implications of the “patent cliff” by examining how parties deal with the event at arm’s length.

The “patent cliff” is the near simultaneous expiration of patent protection for a large number of blockbuster drugs. The patents for at least half of the top 10 branded pharmaceutical products (based on 2011 sales) will expire by 2015. Rapid generic entry is expected for a number of these products, and generic alternatives will likely erode a majority of sales for these products. Research firm EvaluatePharma estimated that the branded pharmaceutical industry lost US$33 billion in revenues in 2012 alone, with a further US$223 billion in sales at risk between 2013 and 2018 due to patent expirations.

Patent Expiration and Transfer Pricing

Patent expiration has been challenging for Big Pharma from a tax perspective. Big Pharma are typically sophisticated with respect to their supply chain structures, recognizing that value is driven in the industry by three broad functions: R&D, manufacturing and sales/marketing. A common supply chain configuration within the branded pharmaceutical industry is one where risks and rewards are limited to a small number of affiliated companies, with functions such as manufacturing and distribution being performed on a contractual, fixed-return basis.

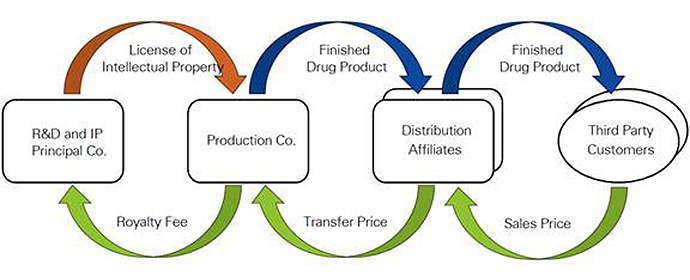

In a typical example, the intellectual property related to the drug is owned by R&D Co., which licenses the right to make, use and sell to Production Co. for an arm’s length royalty on net sales. Production Co. sells the finished product to related affiliates that detail and distribute the product on a limited-risk basis and earn a margin on net sales. Any losses associated with product launches or other major commercial risks are pushed back to Production Co. Since R&D Co. and Production Co. together bear the commercial risks related to the development and manufacture of the drug, they are generally entitled to the lion’s share of the profit.

With a set royalty rate, however, R&D Co. is sheltered from risks related to ongoing product profitability. In such an intercompany pricing arrangement, Production Co. is the recipient of “residual” profit and acts as the entrepreneur.

How does patent expiration affect this structure? Patent expiration may lead to declining sales. The distribution affiliates’ profit and R&D Co.’s royalty income will decline in proportion to sales but Production Co.’s income declines in proportion of the overall profitability of the product as well. This means that even if the overall product continues to record a modest profit, the entrepreneurial entity may be driven into a loss position.

Entrepreneurial entities in pharmaceuticals, i.e. Production Co.’s, are occasionally located in jurisdictions such as Ireland, Puerto Rico and Singapore. When patent expiration reduces total system profits for a vertically integrated business, it can become tax-inefficient for entrepreneurial entities to subsidize profits in the R&D and Distribution Affiliates. Research shows that several pharma giants have been to a great extent reliant on certain blockbuster drugs recently fallen from or soon to fall off the Patent Cliff. If these pharma giants employ the above supply chain for their blockbuster drugs, they will have to evaluate whether their Irish, Puerto Rican or Singaporean structures are leaking income and, if so, what will be the cost to relocate functions currently performed in those jurisdictions.

What Generates Value after Patent Expiration?

It is exceptionally difficult to disentangle the drivers of the premium profits earned on pharmaceutical product sales even when the product is on patent. How can one separate the value of the R&D from the value of the sales/marketing when much of the budget for sales/marketing may include providing samples of the product itself and copies of clinical trial studies that were funded through R&D budgets? How different would it be if the sales/marketing expense includes clinical trials to expand the product label? Once a doctor has success with patients on a particular drug for a chronic condition, he/she may be highly likely to continue prescribing that product. Is this due to the safety and efficacy profile of the product or the skill of the pharmaceutical representative in promoting the product over similar therapies, or both?

Patents and their enforcement are intended to defend a company’s intellectual property (IP) related to the R&D investment in a particular molecule. Upon patent expiration, this IP becomes available to competitors. One might argue that upon patent expiration, the R&D investment no longer generates value. As a result, perhaps the value created by manufacturing assumes more importance after patent expiration. Similarly, one might argue that detailing the product becomes increasingly important.

At best, the importance of the IP related to a particular molecule is reduced as a result of patent expiration. Since the investment in this IP is typically compensated through royalties in licensing arrangements, the natural conclusion is that a re-evaluation of this royalty compensation is necessary once this patent has expired.

How Should the Compensation Change?

As always with intercompany pricing arrangements, we must explore what transpires between unrelated parties that enter into similar transactions in order to determine the appropriate change in transfer pricing policies to reflect patent expiration and generic entry. That is, we must determine whether such behavior is consistent with the arm’s length standard. To find examples of this, we searched for contracts for similar transactions in the public domain. We searched for licensing or development arrangements with clauses outlining the course of action in the event of patent expiration for pharmaceutical products.

We isolated 136 agreements with relevant continuing payments. Nearly 75 percent of the agreements had specific clauses that addressed patent expiration and/or generic entry. The financial terms were redacted for a vast majority of these agreements; as a result, we were only able to observe the direction of change in payment terms as opposed to the magnitude for most of these agreements. Among these agreements with royalty rates or similar fees, we found that there were four possible events that were triggered by patent expiration:

- The arrangement will remain unchanged;

- The arrangement will be renegotiated by the parties;

- The agreement will terminate and the rights will revert back to the licensor; and

- The arrangement will continue but the compensation will change.

By far the most common outcome was for licensing arrangements to continue with a change in compensation. Among these 66 arrangements, there were three types of changes observed. We were unable to determine the direction of the change for 12 of these arrangements as the terms were heavily redacted. Another 49 agreements specified a reduction in the royalty rate upon patent expiration/generic entry. Finally, in five arrangements, the royalty rate became zero upon patent expiration, with the licensee’s obligations considered fully paid-up.

The critical point here is that we were unable to find a single instance in which there was there was an increase in compensation to the licensor as a result of patent expiration and/or generic entry. We submit that this is strong evidence that such behavior would be inconsistent with the arm’s length standard.

Issues to Consider

The “patent cliff” calls for a re-evaluation of transfer pricing in the branded pharmaceutical industry. Many companies, including Big Pharma companies, are already accounting for patent expiration and generic competition in their third party contracts. Companies that do not consider the transfer pricing implications of the patent expiration of their product portfolio may be left with the dilemma of profits in high-tax jurisdiction and losses in low-tax jurisdictions, as well as policies that are simply out of sync with arm’s length behavior. Ideally, this exercise can be done through an evaluation of each company’s current transactions with third parties.

A common approach applied to this situation at present within the branded pharmaceutical industry is to reduce the royalty rate to a “trademark-only” royalty rate, such as 2 percent of sales. This is intended to reimburse the patent-holder for the continued use of the brand, which may continue to generate value. However, this one-size-fits-all approach may not be the appropriate response. A 2-percent royalty rate will not be applicable for all products and all markets, in all cases. Specifically, a broader conversation about the functions that drive post-patent brand value should be initiated.

As we stated in Part 1, three broad functions drive value for pharmaceuticals: R&D, manufacturing, and sales/marketing. Our research illustrates that upon patent expiration, R&D’s compensation should decrease. As a result, it would be prudent for both manufacturing and sales/marketing companies to re-evaluate their value contribution upon patent expiration and then to re-evaluate transfer prices accordingly.

Warren Novis is a senior manager in KPMG Canada’s Global Transfer Pricing Services group. Warren has assisted clients worldwide with complex transfer pricing matters. Molly Minnear is a principal in KPMG’s Economic and Valuation Services practice. She specializes in the planning, documentation and defense of intercompany pricing of tangible property, intangible property, and services. Rowena Ashan is a manager in KPMG Canada’s Global Transfer Pricing Service group. Rowena specializes in transfer pricing for financial services transactions and for the pharmaceutical industry.