Businesses participating in Louisiana’s Enterprise Zone program reported creating more than 9,000 jobs in 2009. Yet after an evaluation, Louisiana’s economic development agency said the program had only created 3,000 jobs that year.

When it took a closer look at the Enterprise Zone program — which rewards companies that grow employment — the agency noted that many of the jobs were not really new at all. Instead, they were merely displacing existing jobs.

What Louisiana’s study of the Enterprise Zone program shows is that there is a big difference between a thorough evaluation of a state’s return on investment and simply reporting the number of jobs companies are creating or the dollar value of their investments.

To accurately measure an incentive’s results, states need to consider whether businesses receiving benefits would have made the same investments had the tax break not existed. When the Minnesota Legislative Auditor’s office studied the state’s Job Opportunity Building Zones program, for example, it found that about 80 percent of the jobs created by companies receiving incentives would have been created even without the help.

States also need to consider how their results would compare if the money had been used for some other economic development program — or for something else entirely. In Oregon, researchers who examined the state’s Business Energy Tax Credit found that the program increased wages by nearly $168 million. But they also found that the net wage growth from the tax credits was only $17.5 million because investing the money in education, health care and other services would have raised wages too.

When states engage in this kind of rigorous analysis, they often find some incentives that are achieving the state’s goals and others that are not. Evaluations frequently identify ways that incentives in both categories can work better. One Missouri review found that in two cases incentives intended to encourage local processing of the state’s agricultural goods were going to out-of-state facilities. Since policymakers were trying to help businesses in Missouri, the legislature changed the law to ensure that only in-state facilities benefited.

Improvements like that are important because tax incentives are one of the most commonly used economic development tools, costing states billions of dollars a year. With that kind of money at stake, states increasingly recognize that they need reliable answers about their tax incentives. After all, when they forgo revenue by offering incentives, states have less money to invest in education, transportation and health care. Yet policymakers do not want to miss opportunities to supply incentives that would improve their states’ economies, their fiscal health or the lives of their citizens.

How States Are Doing

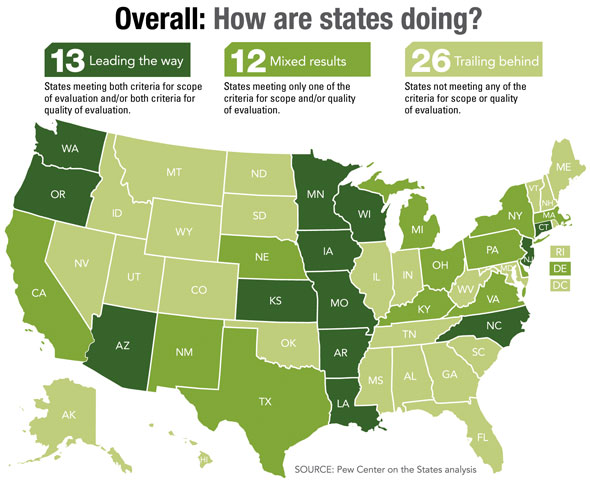

The Pew Center on the States released a report, Evidence Counts: Evaluating State Tax Incentives for Jobs and Growth, earlier this year that asked a key question: Do state policymakers have reliable evidence of whether their tax incentives deliver a strong return?

In our report, we found that none of the 50 states regularly and rigorously tests whether incentives are working and ensures that lawmakers consider hard evidence when deciding whether to use incentives and how to use them. In fact, 16 states had not evaluated a single one of their economic development tax incentives from 2007 to 2011.

Evidence Counts also looked at the quality and scope of states’ evaluations. Some states, including Louisiana and Minnesota, have rigorously examined certain tax incentives, but have virtually ignored others. Another group of states are taking a more comprehensive approach, though even they do not evaluate all of their incentives thoroughly enough.

Still, there is important progress occurring in some places. Washington created a citizens commission in 2006 to evaluate all of its tax incentives on a 10-year schedule. Aided by non-partisan professional staff from the legislative auditor’s office, the commission makes recommendations to the legislature on a set of incentives each year. With this commission in place, Washington is now focused on improving the quality of the evaluations.

In Oregon, elected officials take the lead. Under a 2009 law, tax credit programs expire every six years unless lawmakers extend them. When the first group of incentives was set to sunset in 2011, the legislature created a tax credit committee, which received testimony from businesses that receive the credits, state agencies that administer them and the public. The review led to major changes, including a redesign and scaling back of the state’s Business Energy Tax Credit, which had become far more expensive than originally intended.

Demanding Answers

Oregon launched its review because of a growing sense among elected officials that tax incentives weren’t receiving enough scrutiny. While most state spending receives at least a minimal level of oversight when lawmakers write a new budget, tax incentives often continue year after year without being reviewed. Given the dollars and the jobs at stake, a growing number of state leaders believe that has to change.

That sense is reflected in the reaction Pew has received since we published Evidence Counts. Policymakers and agency officials in more than 10 states have reached out to us for help on how to best evaluate their tax incentives. Louisiana formed a new legislative commission to study the economic results of all of the state’s tax incentives and report back by February 2013. A Massachusetts commission that included many of the state’s top policymakers recommended last spring that the state regularly evaluate its tax incentives.

So the momentum for change is building. Policymakers remain committed to bolstering their economies but are realizing that that they cannot afford to give businesses a blank check. They need evidence of results.

Jeff Chapman is a research manager at the Pew Center on the States, where he oversees a portfolio of work designed to provide states with the critical data they need to improve their economies and build a sustainable fiscal future.