The National Institutes of Health made news this week when it announced it plans to substantially reduce the use of chimpanzees in NIH-funded biomedical research and designate for retirement most of the chimpanzees it currently owns or supports. NIH Director Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. accepted most of the recommendations made by an independent advisory council for implementing a set of principles and criteria defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for the use of chimpanzees in NIH-funded research.

NIH plans to retain but not breed up to 50 chimpanzees for future biomedical research. The chimpanzees that will remain available for research will be selected based on research projects that meet the IOM’s principles and criteria for NIH funding. The chimpanzees designated for retirement could eventually join more than 150 other chimpanzees already in the Federal Sanctuary System. The Federal Sanctuary System, established in 2002 and operated by Chimp Haven.

The news followed the June 11 announcement by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of a proposal to classify both wild and captive chimpanzees as endangered.

“Americans have benefited greatly from the chimpanzees’ service to biomedical research, but new scientific methods and technologies have rendered their use in research largely unnecessary,” said Dr. Collins on Wednesday, June 26. “Their likeness to humans has made them uniquely valuable for certain types of research, but also demands greater justification for their use. After extensive consideration with the expert guidance of many, I am confident that greatly reducing their use in biomedical research is scientifically sound and the right thing to do.”

The new policy does not apply to other non-human primates or other animals. Collins stressed that NIH will continue to use other non-human primates and animals to advance research until there are reliable, alternative models available.

During a visit to the 500-acre Tulane National Primate Research Center six months ago, I asked Dr. Andrew Lackner, the center’s director, whether technology and simulation had decreased the need for non-human primate research. He had a decidedly different take.

“It means you need more,” he said, noting the back-and-forth between models and real life. “Biological systems are incredibly complex … Thus far, it actually has made more work.”

This week at his press conference, Collins was asked a follow-up question about the reduction of chimp research possibly leading to more research on other non-human primates, and his answer fell more technically in line with Lackner’s earlier response.

“This set of decisions today relates solely to chimpanzees,” said Collins, adding that “no one should assume that this has larger implications across the use of other kinds of non-human primates or other animals. And, we [at] NIH continue to feel that animal research is critical for learning critical things that we need to know in terms of understanding and how to prevent and treat and cure disease.”

The Numbers

The Tulane center employs 320 people and supports research projects of more than 400 investigators. It’s also part of a unique culture for biomedical research: Lackner said Tulane is the only institution in the nation with a national biosafety lab, a primate research center, a school of medicine and a school of public health.

Faculty at the center average more than $1 million in funding annually, and the center has supported more than 260 awards from the public health service totaling more than $230 million. Lackner said awards to date in November 2012 were up by 20 percent over 2011.

Tulane’s is one of eight NIH-supported primate research centers (soon to be seven, as Harvard closes down its New England Center). Tulane does not have chimpanzees on the premises, but it does have nine other species, primarily macaques. According to the USDA tallies, Tulane uses or holds more than 5,700 non-human primates. Disease models studied there range from AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis to diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Research is also conducted in such areas as gene therapy, drug abuse and neuroscience. One hundred and fifty studies were in progress as of late 2012 at the Tulane facility, which has two Biosafety Level 3 facilities on site.

Chad Roy is one of Lackner’s star faculty, and oversees the major BL-3 facility, a 22,000-sq.-ft. facility that has nine animal suites and cost $35 million to construct ($10 million from Tulane and most of the rest from NIH). As he explained it, BSL-2 requires FBI background checks. BSL-3 requires an iris scan. The facility is built on 150 cement columns underneath, and has windows rated for winds of 250 mph.

A stone’s throw away is the original home of Guido Alexias, the original owner of the property, which is in the process of being preserved, moved and restored as an eventual welcome center. Made entirely of cypress, it has therefore avoided termite infestation. It also has a certain indestructible mystique as the only building on site left undamaged by Hurricane Katrina.

According to the National Association for Biomedical Research, less than one-quarter of one percent of all laboratory animals needed in the U.S. are non-human primates. Approximately 30 different species are studied by the research community.

The center’s mission is “not tremendously different from a research hospital,” said Lackner. “We conduct research on human health problems that require the use of non-human primates.” NIH first promulgated the use of non-human primates for biomedical research in the 1950s, and the first center opened in 1962. The Tulane center’s focus on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases harkens back to the 19th century malaria epidemic that struck Louisiana.

“You usually think of exotic faraway lands — things happen in Africa and Asia,” Lackner explained. “But North America and Europe are really where most of this happens. Because the globe is so interconnected, and you have the best developed health care and densest populations, this is where things happen. Dengue fever is moving north. This will be an important resource in terms of protecting against infectious diseases.”

That partially explains why the complex recently added about 60,000 sq. ft. for more animal research space. Now, said Lackner, “there’s no place to put people,” so future plans call for adding another 180,000 sq. ft. All told, some $80 million is being spent on construction and renovations. Until now, he said, commercialization “has not played a role in the mission” of the center, but “that’s the direction we’re starting to move now.”

Until recently, because federal money was paying for everything, NIH-funded investigators came first, public health came second, and the for-profit sector was last. “There was nothing left to offer to a private entity,” he said. But investment from the university and the State of Louisiana has given the center more flexibility. Lackner said preliminary discussions were under way about potentially constructing another building.

The Trade-Offs

The NIH news cast light on the topic of animal research in general — always controversial, and increasingly so (for most) as the animals in question begin to resemble humans.

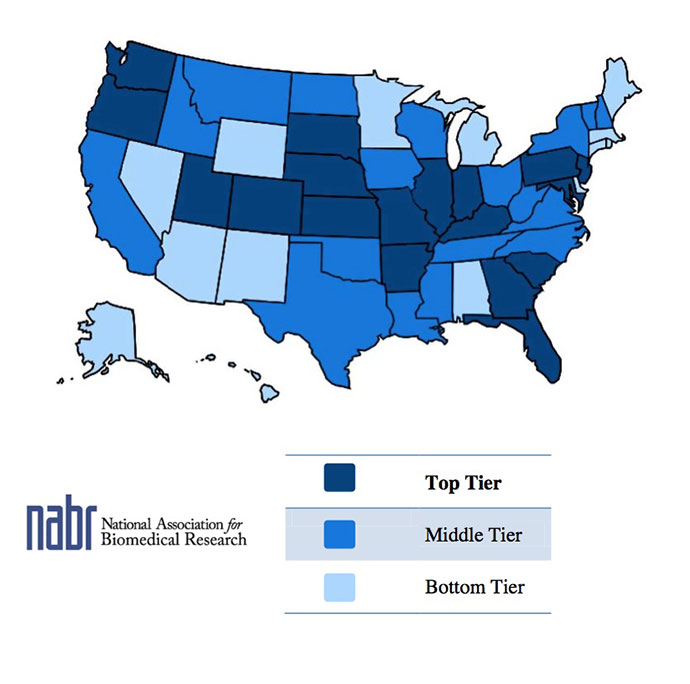

The map above reflects the findings of 2013 state law rankings issued by the National Association for Biomedical Research (NABR), analyzing state-level protections for biomedical researchers and facilities.

According to USDA Annual Reports, in 2012 some 191 organizations ranging from big pharma to big universities used or held more than 107,000 non-human primates. Most are in labs. Some are in more unusual locations, such as uninhabited (by humans) Morgan Island, S.C. The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources leases the island to Charles River Laboratories, which manages a colony of approximately 3,568 monkeys for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Many of those animals are in facilities where human beings are too, and those human beings have increasingly come under scrutiny by animal rights activists. Lackner noted as much in recounting the history of the Tulane property, which used to be “a really sleepy place” across Lake Ponchartrain from New Orleans. There were no fences, and people referred to the area as the Tulane forest. Today, he says, “all centers have significantly increased their security. We now have a 24-hour Tulane police presence, fences and more than that. It’s where we’ve gotten to, and reflective of the level of discourse about anything — the middle has dissolved.”

The National Association for Biomedical Research just released an analysis of where states rank in terms of having laws on the books friendly to biomedical research. “It may be important to a company looking to build or buy a facility in a certain location,” says Matthew R. Bailey, NABR vice president. “If animals are being used, or there are plans to use animal models at a facility, whether that state’s laws are strong enough to protect the institution should they come under fire from animal-rights extremists would be a factor in their decision-making process.

Among the criteria examined were protection laws for research facilities; research exemptions from animal cruelty laws; and exemptions for animal researchers (as for law enforcement personnel) from open records laws in the interest of personal safety. The NABR analysis also awarded points for having laws that penalize cyberstalking and electronic harassment, regulate residential picketing activity, and prohibit the wearing of masks during protests. Florida moved up from No. 25 in 2011 to No. 17 this year because of stricter laws regarding electronic harassment. Wisconsin moved from 29th to 24th because it implemented “a more effective and comprehensive exemption for biomedical research in the state’s animal cruelty laws.”

The Top Ten in the

NABR’s top tier:

- 1. South Dakota

- 2. New Jersey

- T3. Oregon

- T3. Georgia

- T3. Kansas

- T6. Colorado

- T6. Indiana

- T6. Maryland

- 9. Washington

- 10. Kentucky

NABR this week issued a fact sheet reminding the public of the chimp’s contribution to research:

“While a significant amount of work with chimps is behavioral in nature, the role that they have played in biomedical research has been significant, and has provided us with vaccines against hepatitis B and hepatitis A, infectious diseases that according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) still infect as many as a million Americans every year, and annually cause more than 620,000 deaths worldwide,” said the NABR. “Chimpanzees remain an invaluable resource, and are unique because they are susceptible to many major health risks for humans, and therefore play a critical role in research on hepatitis C, malaria, and HIV,” as well as making contributions in stem cell and cancer research.

Asked about whether the principles applied by the NIH to chimp research might be applied to other non-human primates, Bailey says that is a concern in the industry. “A lot of folks in the biomedical research world are concerned about possible political influence on the ability of scientists to use a particular model for research,” he says.

Certainly the influences are many as the NIH begins to make significant cuts in its programs due to sequestration. And so finding the proper balance between animal welfare and human welfare continues to be the challenge, even as certain species like chimps get a free pass.

In her book “Frankenstein’s Cat: Cuddling up to Biotech’s Brave New Beasts,” journalist Emily Anthes peers into bioengineering and animal manipulation, bringing up the same issues in the context of genetic tinkering that have been there for decades in more general terms:

“Most thinking, feeling humans, I think, would say that they don’t want animals to suffer,” she told NPR’s Terry Gross recently, “but a lot of us — the majority of Americans — surveys show, also accept some sort of animal research and experimentation … Most people, for instance, would say that they’re willing to see some mice engineered to get cancer if it cures human cancer, but they’re less willing to see mice suffer if we’re just looking for a cure for baldness.

“It’s really something we have to tackle on a case-by-case basis,” she observed, “based on what the potential benefits for humans are versus the cost to the animals themselves.”