China’s trillion-dollar Silk Road plan is steeped in historical precedent going back to the Han dynasty two millennia ago. The way forward for this massive global infrastructure loop is anything but smooth. But while pundits and policymakers hem, haw and predict, some of the world’s leading logistics firms are getting busy.

Nearly one year ago, in advance of the October 2015 release of China’s 13th five-year plan, the People’s Republic released its “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) vision document, adding further dimension to a global transport infrastructure plan originally announced in October 2013 by President Xi Jinping — and steadily promoted ever since. It’s backed in part by the Chinese government’s $40-billion Silk Road Fund, as well as $50 billion from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

“The initiative to jointly build the Belt and Road, embracing the trend towards a multipolar world, economic globalization, cultural diversity and greater IT application, is designed to uphold the global free trade regime and the open world economy in the spirit of open regional cooperation,” says the vision.

Analysis and debunking have ensued from all the corners of the Earth that the new Silk Road wants to connect, as some wonder whether uniting the world is synonymous with dominating it, while others bemoan cost.

Some of the clearest insights come from Bert Hofman, the World Bank’s Beijing-based country director for China, Mongolia and Korea in the East Asia and Pacific Region. In a December 2015 post, he explains that the Belt will be cinched over land while the Road’s primary surface will be water:

“The ‘Belt’ is a network of overland road and rail routes, oil and natural gas pipelines, and other infrastructure projects that will stretch from Xi’an in central China through Central Asia and ultimately reach as far as Moscow, Rotterdam, and Venice,” he writes. “Rather than one route, belt corridors are set to run along the major Eurasian Land Bridges, through China-Mongolia-Russia, China-Central and West Asia, China-Indochina Peninsula, China-Pakistan, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar.

“The ‘Road’ is its maritime equivalent,” he continues, “a network of planned ports and other coastal infrastructure projects that dot the map from South and Southeast Asia to East Africa and the northern Mediterranean Sea.”

Hofman posits that if a formal OBOR agreement were solidified, it would rival the just-concluded Trans Pacific Partnership trade agreement in impact. China estimates OBOR will generate more than US$2.5 trillion (€2.35 trillion) in annual trade within the next 10 years.

A piece last month in Hong Kong Economic Times touts the potential of OBOR for Hong Kong, especially e-commerce. In July 2015 analysis, Qu Hongbin, chief China economist and co-head of Asia Economics at HSBC, wrote, “China’s new silk road is an updated version of the nation’s going-out strategy. China’s outbound direct investment has been surging by up to 30 percent a year. One Belt, One Road will ensure that China’s overseas investment growth is maintained at a sustainable pace.”

But Beijing-based Bloomberg reporter Michael Schumann, writing in November 2015, is less sanguine, citing stalled Chinese projects around the world as evidence: “The program’s designed to forward Beijing’s strategic and economic interests around the world — at the expense of the West’s — and offer lucrative opportunities abroad for Chinese companies enduring a slowdown at home. In the end it’s a boondoggle that could set back China’s reform, expose its banks to financial risk, and alienate the very nations it’s meant to woo.”

Let’s Get Moving

As the economists sort things out, freight movers are doing the same, with more concrete results.

In 2014, UPS unveiled less-than-container-load (LCL) rail service in addition to full-container-load (FCL) for the 5,000-mile journey from China to Europe, expanding the UPS Preferred multimodal freight portfolio. Most estimates say a rail-enhanced route gets things delivered in about two weeks — an affordable compromise for many caught between the long lead times of ocean shipping and the high price of going airborne.

“China’s manufacturing transformation, which UPS refers to as ‘Made in China 2.0,’ is driving our customers’ need for multimodal transportation options,” said Jeff McCorstin, president, UPS Global Freight Forwarding, Asia Pacific. “UPS Preferred LCL rail service will help our customers manage costs and optimize time-in-transit needs.”

According to UPS, customers using UPS Preferred FCL rail service have saved 65 percent, on average, on costs vs. air freight movements between China and Europe, and gained a 40-percent improvement in transit times compared with traditional ocean freight. Customs documentation is completed at shipment origins in Chengdu or Zhengzhou, China, and with final clearance at the rail termination point in Lodz, Poland, or Hamburg, Germany.

Steve Flowers, president of UPS global freight forwarding services, wrote in the company’s Longitudes blog last summer that the new Silk Road was finally connecting cities such as Chongqing and Chengdu that had seen manufacturing growth due to China’s “Go West” movement, but had been stymied by logistics hurdles. He said it’s already helped cement connections with Japan and Korea, noting that “just last year, the first-ever shipment of electronics from Korea made its way to Europe via rail.”

Links In the Chain

DHL Global Forwarding is not sitting still. And its plan makes use of a nation whose role linking East and West is just as ancient as the Silk Road.

In December, the company announced its inaugural service on the new Southern rail corridor between China and Turkey. Freight travelling via the corridor departs from Lianyungang, China, and traverses three Central Asian countries — Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia — as well two sea transit segments and is expected to take around 14 days, depending on travelling conditions, before arriving in Istanbul, with the option for immediate forwarding by truck to any Turkish city.

“Negotiating the complex transnational requirements that span the Silk Road Economic Belt is no easy task,” said Kelvin Leung, CEO, DHL Global Forwarding Asia Pacific. “It requires a deep understanding of the varying regulatory and infrastructural conditions in each market, robust partnerships with local-market experts and authorities, and experience in brokering cross-border connections without compromising on overall speed and efficiency. Global freight providers such as DHL have a critical role to play in making the new Silk Road an economic reality.”

Central to the plan are DHL agreements with regional logistics and government partners that make optimal use of assets along the way, such Kazakhstan’s commercial hubs, including the newly-created Khorgos Special Economic Zone.

“Trade between China and countries along the Silk Road has grown 19 percent every year on average for the past decade, and the establishment of One Belt, One Road will only further ignite these already-high volumes of economic activity,” said Steve Huang, CEO, DHL Global Forwarding China. “Turkey already counts China as its second-largest source of imports, and the EU as its largest export market. New corridors like the Lianyungang-Istanbul link will only further boost Turkey’s strategic importance and associated economic development as a conduit for trade between China and Europe.”

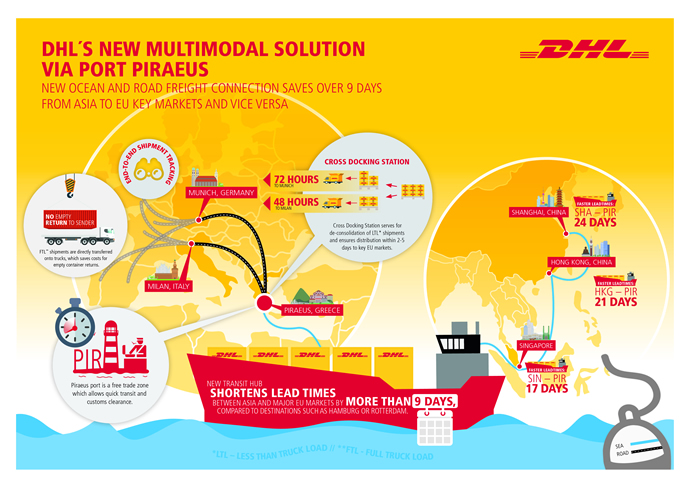

The December announcement followed November news that DHL was expanding ocean and road freight connections between Europe and Asia, Northern Africa and the Middle East via development of a new transit hub in Piraeus, Greece, with service that DHL says “saves over nine days of transit time compared to traditional ocean freight destinations such as Hamburg or Rotterdam.” Piraeus port is a free trade zone, which allows quick transit and customs clearance. From there, cargo moves through DHL Freight’s road freight network to gateways in Munich or Milan within 72 and 48 hours, respectively, and then further to the final destinations. DHL says total transit time from Asia to all major European markets thus is cut from 31-35 days to 22-26 days.

“This new multimodal solution via port Piraeus allows us to provide our customers with faster lead times between Europe and megacities such as Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Singapore, along the maritime route of the ancient Silk Road,” said Kostis Soukoulis, country manager Greece, DHL Global Forwarding, Freight. The company hopes to further expand its multimodal service offering from Piraeus to rail and air freight transport modes in the future.

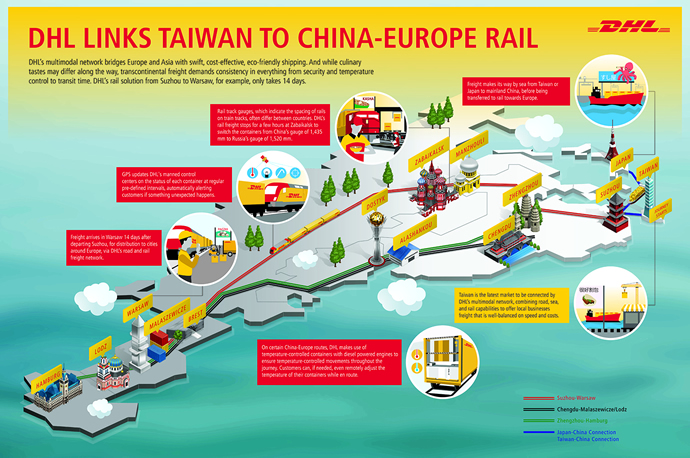

Also in November, DHL added Taiwan to its North Asia multimodal network. The sea link connects Taichung port to Shanghai with a rail link to Warsaw via Suzhou, which also serves as a base for over 10,000 Taiwan-funded export-oriented enterprises. DHL now offers three multimodal rail services between mainland China and Europe.

According to the company, the new multimodal Taiwan-China-Europe service — similar to the Japan service originating from Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe and Hakata DHL launched last year — will offer freight costs savings of up to 85 percent.

“Taiwan has been pushing different initiatives — including the free economic pilot zones plan which looks at key high-end, high value-added service industries such as logistics for innovation — to accelerate its integration into the regional economy,” said Kenny Mok, managing director, DHL Global Forwarding Taiwan. “Taiwan’s industries will need to rely on highly specialized global logistics services to meet the requirements of international trade.”

Earlier last year, DHL also added a third route to its China-Europe multimodal network — the westbound and eastbound Zhengzhou-Hamburg service which complements DHL Global Forwarding’s two established routes. The first is a weekly scheduled block train service along the trans-Kazakh West Corridor rail service that originates from Chengdu, a hub for high tech goods, automotive and other industries, and the main distribution center for Western China, to Lodz in Poland. The second – also weekly – via the trans-Siberian North Corridor serves the manufacturing and commercial centers of Shanghai, Suzhou and surrounding areas and runs both westbound and eastbound services between Suzhou and Warsaw.

Other firms catching a piece of the action include California-based supply chain solutions firm UTi Worldwide, which in August 2015 launched guaranteed weekly rail freight service between China and Europe. The UTi “Iron Silk Road” rail service’s first link is between Harbin and Hamburg, featuring lower rates than air freight and shorter transit times than ocean freight (15 days, eastbound or westbound).

“Other major destinations in northern China and northern Europe, including ports, are accessible within a few days without additional on-carriage charges,” said the company.

The service’s first runs (eastbound, 41 containers; westbound, 46 containers) included automotive equipment, consumer goods and other freight.

Harbin is the capital of China’s northeastern Heilongjiang province, which the nation has targeted for economic development. The UTi rail service is part of a joint venture agreement with strategic partner Changjiu Logistics, the leading independent automotive logistics company in China; Harbin Railway Bureau; and Dalian Port Investment Corp. The joint venture company’s name is HAO Logistics Co., Ltd.

“This is only the first link in our Iron Silk Road rail service and only one of the many ways we are serving the logistics requirements of automotive, aerospace and other manufacturers,” said Ditlev Blicher, UTi president, Freight Forwarding. In December, the firm introduced new multimodal hubs in Kuala Lumpur and Ho Chi Minh City to “tackle the challenges of static air cargo capacity and service its Worldwide Gateways in Europe and the USA.”