Drive southwest from downtown Vancouver toward the ocean, past parks full of dogs, the queued ships in the channel, and multimillion-dollar homes looking out from Point Grey on English Bay, mountains and forest, and you’ll come to the campus every Canadian student wants to visit: the University of British Columbia.

Home to more than 40,000 students, UBC is the second-largest university in Canada. It is renowned for its pristine setting — and for its quest to keep it that way. The goal? To reduce CO2 emissions by 100 percent by 2050.

The four-year-old Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability (CIRS), held together by mechanical means in order to deconstruct it at the end of its useful life, is UBC’s LEED-Platinum flagship sustainability project. It’s ground zero for a “living lab” covering the campus’s 400 hectares (988 acres) where multiple solutions are underway: a solar aquatics lab for wastewater cycling; PV and a rooftop garden; a ventilated door invented by students; and a $90-million effort to convert from an antiquated steam-based district heating system to a more modern hot water-based system that better incorporates renewables and geothermal energy.

But the most striking thing to any visitor is the look and aroma of wood, which was used wherever possible instead of cement and steel.

“There’s no technical reason we can’t turn our buildings into instruments of carbon sequestration,” says Alberto Cayuela, associate director of UBC’s Sustainability Initiative and the CIRS. “Our buildings should be able to store more carbon in their structure than was emitted during their construction.” Using wood is one way to that goal: “BC forests grow this much wood in three minutes,” says Cayuela.

Indeed, despite its LNG terminals a bit to the north, wood products continue to be the province’s signature sector, with 55 million hectares (nearly 136 million acres) of productive forest that helped BC export a globe-leading C$5.3 billion worth of softwood lumber in 2013.

But with that much wood comes a good bit of wood waste. And that’s where an industrial waste-to-energy project just a few steps around the corner from the CIRS comes into play.

Nexterra, a 50-employee firm headquartered in Vancouver since its inception 12 years ago, built its first waste wood-to-energy plant six years ago up north in Kamloops for forestry firm Tolko Industries, and in 2013 made the first of what it hopes to be multiple sales in the UK. But it needed to demo its gasification technology, and UBC was the ideal partner. So was British Columbia, the only North American jurisdiction with a carbon tax, and therefore a place where carbon credits could be monetized.

“The market overseas is larger than here,” explains Darcy Quinn, director of business development for Nexterra, with particular opportunities in the UK, Southeast Asia and China. “But you need to test here because it’s costly to send equipment back and forth.” UBC told the company it would go with Nexterra’s solution if its benefits could be achieved within certain cost parameters.

Different Modes

As might be expected in such an environmentally conscious spot, the scrutiny during licensing was intense. There was a lot of public consultation, what Quinn calls earning the facility’s “social license.” The official opening of the Bioenergy Research & Demonstration Facility (BRDF) took place in September 2012, and stood as North America’s first commercial demonstration of a community-scale heat and power system fueled by biomass.

Among the project’s funders were the Canadian federal government (Natural Resources Canada and Western Economic Diversification Canada); the province (via the BC Innovative Clean Energy Fund and the Ministry of Forests, Mines and Lands); FP Innovations; the Canadian Wood Council; and the BC Bioenergy Network.

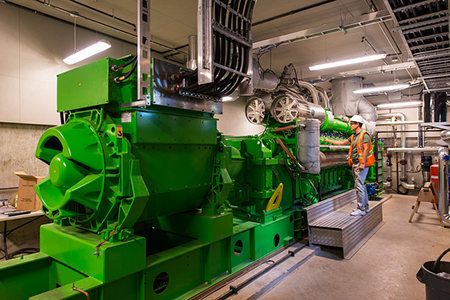

Today the CA$34-million waste-to-energy plant on campus generates 2 megawatts from the tallest cross-laminate building in North America, managing to stay relatively quiet despite the lower-level presence of a GE 20-cylinder Jenbacher engine. According to GE, the Jenbacher has been deployed “to heat, power and provide CO2 for a tomato-growing operation in California, and generate energy from everything from cheese whey to discarded school lunches.”

Quinn is proud of the company’s affiliation with GE, which he calls “a world leader in using low BTU-value gases.” He’s also proud of this fact: “Emissions from this plant are actually lower than from a natural gas plant.”

Wood for the BRDF comes from Cloverdale, a wood aggregator that grinds and delivers the wood waste once or twice a day.

Other feedstocks such as municipal solid waste are also being evaluated, Quinn says.

Central to the BRDF’s business case is its ability to operate in two main operating modes. The first mode, “thermal-only mode,” uses commercially proven gasification technology developed by Nexterra to turn biomass into a clean synthesis gas or syngas. The syngas replaces natural gas used to produce steam and hot water to meet campus heating needs. In thermal mode, the facility generates up to 20,000 pounds per hour of steam, approximately 25 percent of UBC’s base requirement.

The second mode produces both heat and power, using Nexterra’s syngas conditioning system and GE Energy’s high-efficiency gas engine to power an electrical generator. “In demonstration mode,” explains GE, not only does enough steam still get generated to cover 12 percent of UBC’s base requirement, “the system generates approximately two megawatts of electricity, enough to power the nearby 1,600-bed Marine Drive Student Residence.”

Quinn says the school’s reputation used to be ‘If you do something here, we own it.’ ” But UBC, known for its engineering prowess, has loosened its intellectual property restrictions on R&D on campus. Among the research projects underway involving more than 30 campus programs is a backup battery project.

Another added bonus? More power on a growing campus whose geography currently limits its incoming power to 38 MW via a single transmission line. Having multiple sources like the BRDF “keeps them from having to build a new line through some of the most expensive real estate in Vancouver,” says Quinn.