As the global capital of finance, New York City makes money from money. But when have you seen, touched or purchased something manufactured in New York? If you can’t recall, that’s understandable.

Therein lies the uniqueness of the Brooklyn Army Terminal (BAT), a brawny hub of modern manufacturing cast from a former military installation overlooking New York Harbor. Once used as a point of embarkation for troops bound for World War II, the terminal now houses a small army of manufacturers dedicated to craft and thriving in New York City.

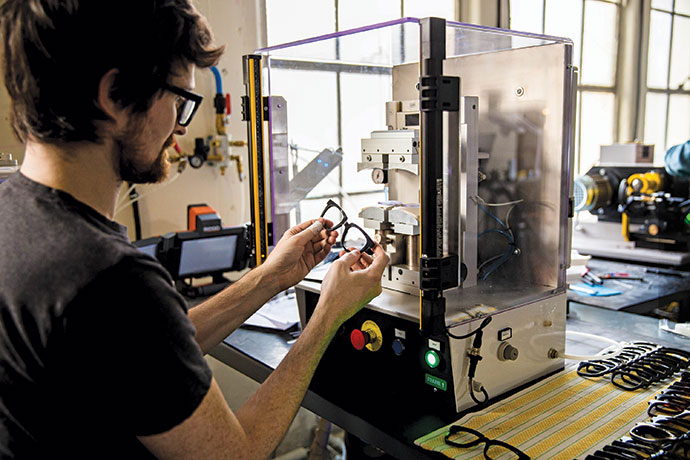

Gerard Masci is one of those makers. A founder of Lowercase, which designs and produces custom eyewear, Masci was so determined to set up shop in his native New York that he spent a year searching for a viable location. He landed at BAT in 2016.

“Being where we are, we’re able to mark all our stuff ‘Made in NYC,’ and that’s just massively important,” Masci tells Site Selection. “We learned early on that the New York brand really resonates with people. They’re like, ‘Wow, things are still made in New York? There’s still craftsmanship there?’ They just connect with it.”

That’s music to the ears of officials at New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC), the quasi-governmental organization that manages the terminal among other municipal real estate assets. With the city having purchased the terminal in 1981, NYCEDC has led a long-running mission to forge it into a breeding ground for manufacturing.

“Because we’re a mission-driven landlord, we’ve been able to turn the Brooklyn Army Terminal into a community-driven industrial center for modern jobs and skills,” says Julie Stein, senior vice president in NYCEDC’s Asset Management Division. “We pride ourselves,” says Stein, “on being an affordable, modern manufacturing hub within the neighborhood.”

Such is the city’s commitment that it has invested several hundred million dollars in rolling renovations to the campus, which includes six buildings spread over 55 acres (22 hectares). Buildings “A” and “B,” the heart of the complex, total more square footage than the Empire State Building.

“… with BAT, the tenant is the priority.”

The terminal’s Annex building, upgraded in 2016 to the tune of $15 million, is devoted to food manufacturing. Growth stage businesses find homes in three micro-manufacturing hubs whose workspaces range in size from 1,500 sq. ft. (140 sq. m.) to 10,000 sq. ft. (930 sq. m.). An on-site job training center, the Brooklyn Workforce1 Industrial & Transportation Career Center, provides a stream of pre-screened applicants.

In all, more than 100 businesses employing more than 4,000 workers operate on the terminal’s grounds.

“BAT is the perfect home for us,” says native Brooklynite Kristine Tonkonow, founder and CEO of the Konery, maker of boutique waffle cones. “We have all the amenities we need plus the room we’ve needed to grow.”

Home Field Advantage

UncommonGoods, an online retailer with a year-round staff of nearly 200, is one of the terminal’s biggest employers. Founder and CEO Dave Bolotsky, who describes himself as a fourth-generation New Yorker, moved the business to BAT in 2008 after outgrowing several Manhattan locations.

Each workday morning, Bolotsky hops a ride-share bike outside his Manhattan apartment and pedals to the NYC Ferry, which takes him across the harbor and docks at the Brooklyn Army Terminal. It’s a half-hour commute — not bad for New York.

“We could go to New Jersey,” says Bolotsky, “but we would lose out on a lot of talent that would not want to commute from the city. The fact that people can get here by subway or bicycle or ferry is a big competitive advantage in terms of attracting talent. And there’s a tremendous pool of talent here in New York.”

That talent includes 2.4 million New Yorkers with a bachelor’s degree or above, more than Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. combined. The city’s tech talent employment increased 44% between 2011 and 2018, according to CBRE. In 2018, venture capital firms poured $11 billion into 9,000 NYC startups.

Given competition for space, finding room in New York to run a large business is a challenge, says Bolotsky. Since leasing 200,000 sq. ft. (18,600 sq. m.) at BAT, though, UncommonGoods has tripled sales volume. Its space includes sections for warehousing, distribution and myriad office functions such as product development, marketing, data analytics, design, tech support and customer service. Despite that multitude of interconnected operations, UncommonGoods, like all BAT tenants, pays rent at an advantageous industrial rate set by NYCEDC.

“The affordability of BAT was essential to us,” Bolotsky says. “I wanted to keep the company in New York to provide living-wage jobs for New Yorkers. But I am not in business to work for the landlord. I would not have made the decision to keep the business in New York City if it weren’t for an affordable option like the Brooklyn Army Terminal. That was an essential part of our decision-making process.”

Built to Last

Having celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2018, the Brooklyn Army Terminal has a storied past. At various times since World War II, the terminal has served as a military prison, a storage space for drugs and alcohol confiscated during Prohibition, and a processing center for refugees from the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Elvis shipped out from the terminal for post-war duty in Europe in 1958.

As if in deference to BAT’s colorful history, today’s tenants represent a far-flung mix of eclectic enterprises. A “Core Four” of industries, says Stein, includes traditional manufacturing, advanced manufacturing, food manufacturing and a category designated “Made in New York,” which includes garment making, film, television and other media production.

“We’re looking for businesses that are within that modern manufacturing frame,” Stein says. “We’re also looking for folks that have quality jobs and job density.”

Inside a staggering 4 million sq. ft. (370,000 sq. m.) of total workspace, BAT’s manufacturing tenants are breaking new ground in disciplines such as technology (Altronix, Wiggby Precision, Makerspace NYC, LeeSpring Co.); life sciences (BioBAT, Calder Biosciences, Chemitope Glycopeptide, IRX Therapeutix, Mega Aid); fashion (Jomashop, Lafayette 148, Marc Joseph NY, Riva Precision Manufacturing, Mudo Fashions, Tailored Industry); food production (the Konery, Jacques Torres Chocolate, Momo Dressing, City Saucery, Green Mustache); and the arts (Rooftop Films, Guggenheim Museum, Mark Morris Dance Group, ArtBuilt Brooklyn).

As the world’s only known maker of flavored waffle cones (think dark chocolate, lavender bud, gingerbread and salted caramel), the Konery is one of BAT’s most creative food businesses. Tonkonow launched the enterprise elsewhere in Brooklyn but came to feel underserved by her landlord. She moved the Konery to BAT in 2017.

“Traditional landlords don’t necessarily have the tenant at the forefront,” Tonkonow tells Site Selection. “But with BAT, the tenant is the priority. With BAT, it’s always about growth, about creating jobs and making it easy to succeed.”

The sheer size of the terminal has given the Konery room to expand. In August, the business moved from BAT’s food annex into a 10,000-sq.-ft. (930-sq.-m.) workspace in the mammoth Building A. Four times the size of the Konery’s previous quarters, the new space provides enough room for the company’s 10 employees, its production machines, packing tables, prep area, drying racks and inventory. Five freight elevators and more than 100 loading docks ease the process of on-loading supplies and shipping out product.

Lowercase’s Masci says BAT’s array of amenities is unlike any he came across during his year-long site search.

“We couldn’t find the combination of everything we needed anywhere else. We needed a concrete floor that can support our heavy equipment and heavy power to run it. We had to have running water. The loading docks and multiple freight elevators are super important. It’s not hard to find any one of those things, but finding all of them together is nearly impossible.”

Masci is wowed by the terminal’s architecture and awed by relics from World War II, including signs still hanging in the cavernous atrium denoting destinations for soldiers shipping off to battle. He’s even designed a line of sunglasses based on the chunky, black frames of the military.

“That was literally born out of us being in this building all the time,” he says. “Being here is part of what’s exciting about coming to work every day.”

A Glimpse of the Future

Tailored Industry, a BAT tenant since 2018, is on a mission to revolutionize the way that fashion goods are produced and distributed. A supplier of knitwear to name-brand retailers, the company is pioneering on-demand, technology-driven production and ultra-swift delivery to accommodate fluctuating inventories.

Using speedy, 3D knitting technology and proprietary distribution software, Tailored Industry can shrink the typical year-plus production cycle to as little as a few weeks, says CEO Alex Tschopp.

“… the New York brand really resonates with people.”

“We enable brands to sample new products and move into production in an incredibly short time,” says Tschopp. “We can achieve essentially the same efficiencies of mass production, but on a per-piece basis.”

Sustainability is one of Tailored Industry’s touchstones. Tschopp says seamless, 3D knitting requires 15% less raw material than traditional methods. Most notably, on-demand production eliminates the typical product surplus that results in dramatic markdowns, unnecessary shipping and storage costs, and associated energy and water waste.

Similarly, says Tschopp, seamless knitting allows for garments that have outlived their uses to be deconstructed into original yarn form, thus extending the life of the raw material. This demonstration of “circular economy,” says NYCEDC’s Stein, is a fitting reflection of BAT’s mission and direction.

“Instead of having a linear life cycle for products, we’re looking at business models that use regenerative business practices. How do we create products that have longer, circular life cycles? And how do we use our space to attract those innovative green companies in New York City’s manufacturing space?

“In terms of the future,” says Stein, “we also think about the connections our campus has to the freight and maritime infrastructure. The 65th Street railyard is just south of the campus and we’re on the working waterfront. So, there’s opportunity for anyone who’s thinking about multi-modal distribution or logistics. These are some of the many things we’re thinking about going forward to continue to create value for our tenants.”

This Investment Profile was prepared under the auspices of the New York City Economic Development Corporation. For more information, email bklyn@edc.nyc.

On the web, go to www.bat.nyc.