In July 2017, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke announced that the Department would offer 75.9 million acres offshore Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida for oil and gas exploration and development. It wasn’t new: Offshore leasing was going on under the previous administration too. But it was one of many steps taken during the year — including, yes, the drastic reduction in the size of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase national monuments — to further maximize the prospects for energy development on public lands.

"Our Outer Continental Shelf lands offer vast energy development opportunities and we are committed to encouraging increased energy exploration and production in these offshore areas to maintain the nation’s global dominance in energy production," Zinke said in July. "As a global energy leader, we will foster energy security and resilience for the benefit of the American people. A strong offshore energy plan that responsibly harnesses more of our resources will spur economic opportunities for industry, states, and local communities, creating jobs and revenue. That’s why we also are developing a new national Outer Continental Shelf oil and gas program that will best meet our future energy needs."

The announcement followed a ceremony in April when President Donald Trump, joined by Secretary Zinke and members of Congress from coastal states, signed the America First Offshore Energy Executive Order, which aims to expand OCS energy exploration and development through review of the five-year leasing program and reconsideration of certain regulations pertaining to offshore energy potential.

"I am going to lift the restrictions on American energy, and allow this wealth to pour into our communities," said President Trump.

California: Energy Capital

In a number of communities, American energy was already doing quite well: In the Marcellus and Utica shale regions in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia, for instance, natural gas production growth (to 17 billion cubic feet per day in 2015) and growth potential caused the U.S. Energy Information Administration to project it would double in the next 35 years, accounting for 40 percent of the nation’s natural gas production.

California can be a land of contrasts, but both sides of the coin point to its value as an energy hub. Lauded worldwide for its progressive environmental and energy policies, the state is also home to 19 oil refineries, producing among other products around 7 million barrels per week of gasoline. Meanwhile, In 2016, turbines in wind farms generated 13,500 gigawatt-hours of electricity — about 6.81 percent of the state’s gross system power.

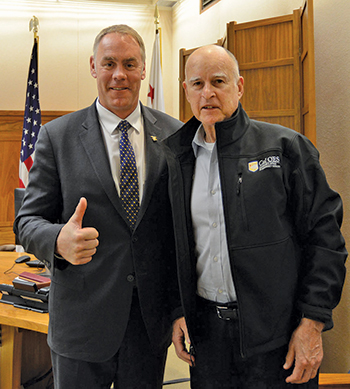

California Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in July 2017 an extension of the state’s cap-and-trade plan to 2030. It had been set to expire in 2020. The law exempts oil refiners, fossil fuel power plants and food processors, among others, from direct emissions regulations, requiring them to buy permits to release greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. The measure also includes tax breaks for some of those same industries.

The move comes even as the state seeks to clamp down further on emissions in general. Eleven years ago, California’s Global Warming Solutions Act (AB 32) set the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. "California is on track to exceed that target, while the state’s economic growth has continued to outpace the rest of the country," said the California Air Resources Board in December, as it approved the 2017 Climate Change Scoping Plan. The plan calls for further reducing climate-changing gases an additional 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, and will require California to double the rate at which it has been cutting emissions of those gases.

Widening the Gulf?

Refiners in the Gulf of Mexico have largely recovered from capacity reductions caused by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma in fall 2017, and related petrochemical investment has rebounded too in such locations as Corpus Christi, where the port commission in December approved a lease agreement with Vitol Inc. and Harvest Pipeline Company for lease of a 22-acre tract for development of a state of the art crude oil export terminal and also approved a lease agreement with Gulf Coast Growth Ventures (GCGV) Asset Holding LLC — an ExxonMobil-SABIC JV — for a 13-acre multipurpose cargo dock and a 35-acre marine terminal facility at the Port of Corpus Christi. GCGV plans to construct and operate a world-scale ethane steam cracker for production of ethylene and derivative units for production of polyethylene, and monoethylene glycol (MEG). The project will use ethane gas from major production areas in the US and export the polyethelene and MEG to markets worldwide.

Like California, this area of Texas likes its energy in all forms too: Also in December, Port Corpus Christi announced it expected to reach a new wind turbine cargo milestone by handling more than 3,000 large wind turbine components including wind turbine blades and tower sections. While those components end up at wind farms across the nation, Texas continues to lead the nation as the no. 1 wind energy industry state with over 20,000 MW of installed wind power capacity. In 2017 wind power surpassed coal-fired power generating capacity in Texas.

Meanwhile, out in the Gulf itself, the Gulf of Mexico OCS, covering about 160 million acres, has technically recoverable resources of 550 million barrels of oil and 1.25 trillion cubic feet of gas, accounting for nearly three-fourths of the oil and a fourth of the natural gas produced on federal lands. As of July 3, 2017, 15.6 million acres on the U.S. OCS were under lease for oil and gas development (2,947 active leases) and 4.1 million of those acres (842 leases) were producing oil and natural gas. More than 97 percent of these leases are in the Gulf of Mexico; about 3 percent are on the OCS off California and Alaska.

On July 6 — reinforcing the theme that America’s independence and its energy independence might be intertwined — Secretary Zinke signed a secretarial order to tackle permitting backlogs and delays, identify solutions to improve the permitting process on federal lands, and to identify solutions to improve access to additional parcels of federal land that are appropriate for mineral development. As of January 31, 2017, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) had 2,802 Applications for Permit to Drill (APD) pending. The five BLM field offices with the highest number of pending APDs were:

- Casper, Wyoming: 526

- Vernal, Utah: 506

- Dickinson, North Dakota: 488

- Carlsbad/Hobbs, New Mexico: 388

- Farmington, New Mexico: 152

“Oil and gas production on federal lands is an important source of revenue and job growth in rural America but it is hard to envision increased investment on federal lands when a federal permit can take the better part of a year or more in some cases," Zinke said.

All in all, it was a year to remember for energy industry proponents wishing to optimize all of the nation’s assets. Zinke summed up his and their outlook:

"I’ve spent a lot of time in countries across the world," he said, "and I can tell you with 100 percent certainty it is better to develop our energy here under reasonable regulations, rather than have it produced overseas under little or no regulations."