In three years time, Botswana will celebrate its fiftieth year of independence. Before it sees another 50, the extensive diamond deposits that have been its source of prosperity will have long run out.

Diamonds, which have been sold as a 50/50 partnership between the government and diamond cartel De Beers since the country’s formation in 1966, currently account for about half the government’s earnings and 70-80 percent of the country’s export earnings. The country is one of the largest diamond producers in the world, but it is estimated that by 2029, most deposits could be used up.

In preparation for this, the country, like many other developing nations, wants to diversify its economy. And, again like many other developing nations, it wants the knowledge, experience and technical expertise that foreign direct investment (FDI) brings in order to do this.

Where Botswana differs from many other developing nations is what it has done with wealth already generated. The country has been called the true success story of Africa. Instead of funding golden palaces and high-end Mercedes, the Botswana government has ploughed funds into improving society, with remarkable success.

Roads Instead of Palaces

“It’s an African country that works,” says Ryan Hoover, portfolio manager at investment advisors the Africa Capital Group. “You can really see the progress. Just after independence the country only had a few kilometres of paved road, and now it has a fully developed transport system.”

The country prides itself on the kind of transparency that results in roads instead of palaces. Earlier this year, Transparency International released its Corruption Perceptions Index for 2012. The guide indexes the scores analysts, experts and business people give countries on levels of government corruption. Over the last decade, Botswana has consistently ranked as the least corrupt nation in Africa. In last year’s results, it came thirtieth in the world, putting it tied with Spain and above developed nations such as Portugal, Taiwan and South Korea.

“I was actually stopped for speeding with a radar gun in Botswana,” says Hoover. “I was impressed. I was shown how fast I was going, given a ticket and not asked for a bribe. It was a small example of how things are above board.”

Added to that, the country has one of the highest literacy rates on the continent with over 80 percent of the total population (and 94 percent of the population aged 15-24) capable of reading and writing, according to the World Health Organization.

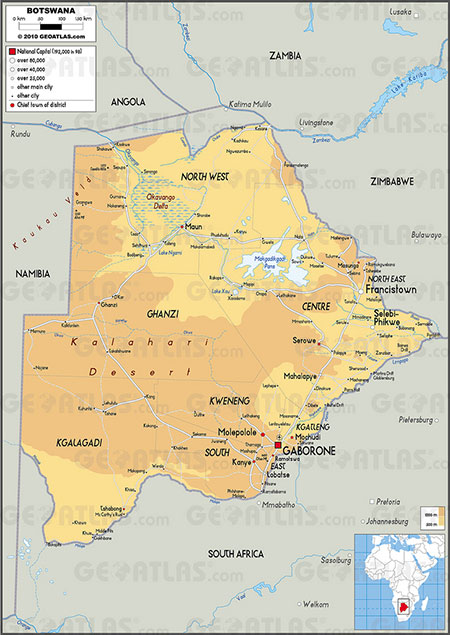

So Botswana is a wealthy, stable, educated country in the heart of sub-Saharan Africa with extensive natural resources. Yet globally, few people know of it. According to Simon Anholt, creator of the Anholt-Gfk Roper Nation Brands Index, Botswana consistently ranks lower in reputation than reality simply because it is African. It can be hard to think of it as a good, stable democracy, he says. The country also suffers from being overshadowed by close neighbours South Africa and, in a more infamous way, Zimbabwe.

It also suffers from some geographical drawbacks that limit its potential as a destination for foreign investment and thus help to keep it in obscurity. It is sparsely populated, contains part of the Kalahari Desert and is landlocked. The latter can be a real problem for generating international investment. Over the last eight years, the country has ranked a middling fifteenth out of all African nations when it comes to attracting FDI, according to global consultancy Ernst and Young.

With no sea access and a limited domestic population, any manufacturer looking to locate there will either have to export within Africa or send product along the Trans-Kalahari highway to South Africa or Namibia. Although Botswana is a member of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) allowing a single excise tariff, the additional road miles will inevitably add to costs.

“For the most part, it is a very small market, and it is affected by its reliance on neighbours, especially South Africa. But it is attempting to address this,” says Hoover. “For instance, it’s attempting to make itself into a regional financial centre.”

The country has worked out an agreement with De Beers so that it stays a major diamond processor after its own reserves run dry. It has established a low corporate tax rate of 15 percent, according to the Botswana Export Development & Investment Authority (BEDIA). It has also encouraged technological and financial start-ups such as the social media platform, Mobbo and consumer lending firm, Letshego. This has enabled it to move away from sectors manufacturing physical goods and towards products that do not need to be transported, says Hoover. “It’s a small market, so it may be more of a niche destination for people,” he adds.

Can a Pharmaceutical Cluster Take Root?

Other areas are primed for investment as well. The country provides free medical care to citizens but imports most of its drugs. The government of Botswana wants to attract manufacturers through public private partnerships (PPPs) but has not had much success. Research and analysis firm Frost and Sullivan estimate that the market for generic drugs in Botswana will be worth £111.3M ($168.8M) by 2015. Branded drugs, more attractive to many pharmaceutical manufacturers, will trail slightly with an estimated 2015 market value of £76.5M ($116.1M).

Thus far, Botswana has not had much success in attracting a pharmaceutical manufacturer due to the small domestic market, the difficulty with exporting overseas and the need to reform patent laws. It has had two proposals for PPPs and one domestic manufacturer that is in the process of setting up.

Gemi Pharmacure, the domestic manufacturer, produces generic anti-retroviral, anti-bacterial and anti-malarial drugs, amongst others. It has started a manufacturing plant in the mining town of Selebi Phikwe that is intended to employ more than 1,300 workers. The project, in conjunction with the government of Botswana and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), was set up in the town in an attempt to diversify its economy.

Although currently the only manufacturing facility in the country, Gemi CEO George Proctor is hopeful that international generic manufacturers can be convinced to set up African manufacturing centres in Botswana. The political and economic stability, high economic growth rate, excellent infrastructure, trade agreements and financial system all make it an attractive choice, he says. Indian and Pacific manufacturers are the most likely to set up in the country, he adds.

“With the experience they had with HIV, they’ve been very progressive in attacking health problems,” says Hoover.

Energy Diversification Plans

Meanwhile, Botswana is also looking to diversify power production. Currently it imports most of its power from South Africa, and what is generated domestically is done through coal combustion. Domestic demand is increasing in Botswana and Eskom, the South African utility company, has had to cut back on the amount of electricity it exports to its neighbour due to growing demand at home.

A second coal-fired power plant is still under construction but it alone will not be enough to meet power generation demands estimated by Frost and Sullivan to be increasing by 4.6 percent every year. As a result the Botswana government is planning to invest about £494M ($750M) in its domestic electricity industry before 2016.

It would like to diversify into renewable energy while doing so. The country is hosting a renewable energy expo later this year. As a concrete step towards generating its own renewable power, it constructed its first solar plant in 2012. The project was funded by Japanese Environmental Grant Aid. It was built by Japanese firms including the main contractor, the Itochu Corporation and Huji Furukawa Engineering and Construction. It cost an estimated £6.5M ($9.9M) and will generate 1.3 MW of power.

If Botswana is to grow as a destination for international investment, fixing its power problems should be priority number one. It is unlikely to attract top foreign talent and expertise if it suffers from rolling blackouts as a result of “load shedding” —systematic shutdowns of part of the grid in order to preserve the rest — from its domestic and imported suppliers. This is especially true outside of cities. “For a manufacturer coming in and looking to build a major installation, this could be a serious problem,” says Hoover.

With about three years before its fiftieth birthday, which is also the target for its current growth plan Vision 2016, time to address these issues is fast running out. The country which is Africa’s success story is going to have to work hard in order to ensure it stays a success story.

Rob Denman is editor in chief and CEO of London-based Pathfinder Business.