Memo to areas hoping to land a Facebook data center: If you can’t make available enough clean and renewable energy at a site under consideration, it won’t be under consideration much longer.

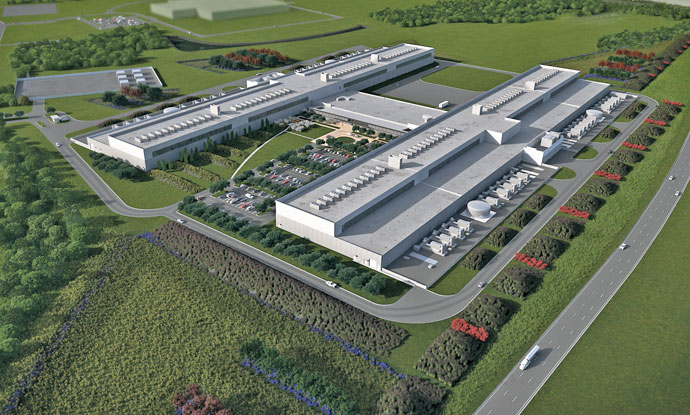

The operative phrase here is “make available” because the energy source need not be at the site. It isn’t at AllianceTexas, the sprawling Hillwood development in Fort Worth, Texas, where Facebook has just begun construction of a 250,000-sq.-ft. (23,225-sq.-m.) data center that will open in late 2016. A new wind farm in Clay County, 110 miles northwest of Fort Worth, will supply the power needed to meet Facebook’s 100 percent renewable energy requirement.

Though central to the location recipe, clean energy is hardly the only ingredient needed when Facebook’s site selection team enters the kitchen.

“We looked pretty much at all 50 states and did very extensive due diligence,” says Rachel Peterson, Facebook’s director of data center strategic engineering. “We’ve sited other data centers in the US but decided now would be a good time to step back and relook at all the states, realizing that there are changes out there on the landscape that we maybe hadn’t heard about, to make sure we were really thorough.”

States are first evaluated in terms of overall costs, but the clean energy criterion soon comes into play. “We spend a lot of time looking at the power picture, and not just in terms of power pricing, which is important. At the end of the day, we have to run our data centers, run our business making sure we understand the costs appropriately. We want locations where we can have 100 percent clean, renewable energy.”

Peterson says additional ingredients are then added to the mix — accessibility, for example. Dallas/Ft. Worth International Airport is just 20 minutes southeast of AllianceTexas. From most locations, including Menlo Park, Calif. headquarters, that’s one flight, not two or more, and a quick ride to the data center.

“That’s of interest to us,” says Peterson. “On the regional level, we look at labor – accessibility of construction crews, ongoing operations labor and which locations are interesting or challenging relative to others. We do look at outside temperature and humidity, but the way we design our data centers, we are able to site in more hot and humid locations without a lot of impact on our PUE [power usage effectiveness], thanks to the great work our data center engineers have done in designing these facilities. So we take that into account, but it’s not something that’s driving the process as much. Natural disaster risk is also something we look at and take into consideration.”

Next, says Peterson, “We tend to drill down and look a bit more regionally within a state — which cities might be interesting, what do the population centers look like, going back to the labor accessibility factor. At the site level, a big consideration for us is that it is pad ready. Facebook’s growth has been steadily increasing, with around 1.5 billion users worldwide right now. Time is of the essence. Finding a site where time-to-market is short is very important, meaning from day one the land is ready to go and we have power to get us started. And we can’t have a data center connected to the Internet of course unless we have enough of a robust network in place as well.”

The Near-Perfect Site

Then come the natural criteria associated with putting an actual building on the site in terms of feasibility, entitlements, ownership of the site — any considerations that might affect Facebook’s ability to develop at the location fairly quickly, explains Peterson. “We also look at whether we can get multiple buildings on the site. Does the size and shape of the site affect us? How does it affect our constructability and so forth? So when we’re at that point, at the site level, we’re in much more intense discussions involving energy and electricity and what delivery might look like for us, what that project in terms of clean, renewable energy might look like, what hurdles do we have to overcome in order to get there, and in what kind of timing? Our goal is to have that available to us from day one. It’s a long list of factors we look at, and sometimes we can’t optimize on all of them. But we definitely have more crucial targets in terms of characteristics we look for, and from there we know what we can make trade-offs on and where we can find the near-perfect site that we’re looking for.”

Peterson says Facebook winds up its year-long due diligence process with two sites, not one.

“If something happens at the last minute and one site falls out of the running, we need another option to move on. In this case, we did have another location, which was great in terms of all the attributes we’ve gone over. But we had a very difficult time putting together a renewable energy solution in that state and at that site both in terms of availability and cost of renewable energy. We tried hard in a lot of different ways to affect both of those angles in the time frame we were working in, and it became clear it wasn’t very feasible at the other site.

“The AllianceTexas site has everything else we were looking for,” adds Peterson. “But one of the major advantages — and why we targeted Texas in the first place — is its deregulated energy market and our ability to have a choice in our energy supply. That, combined with the fact that it has terrific natural wind resources and a lot of projects to choose from, made that part of the equation much easier for us and sealed the deal for us at the end of the day in Texas and the AllianceTexas site in particular.”

Facebook’s thoroughness and ability to remain anonymous were impressive even to seasoned economic developers in the running for the project, known during the due diligence phase as Project Ernst.

The Varsity Team

“It took a year, since July 2014 — it was announced in July 2015,” recalls David Berzina, executive vice president, economic development, at the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce. “They looked at about 120 sites in I don’t know how many states, including four sites in Texas toward the end,” he relates. “They were very secretive, including how email was identified — they had cellphones where you couldn’t tell where the call was coming from. It was a very exhaustive process. They didn’t leave a single stone unturned. They made us work very hard, and I imagine they made the other communities work very hard. They’re very good at their jobs — a lot of their negotiators were lawyers and site selection professionals.”

Berzina says the Fort Worth location fills a geographic void in Facebook’s data center footprint, between its West Coast facilities and a data center in northern Sweden. “They wanted a central location, and they wanted to spread out their exposure. And Texas being an independent energy grid was important to them.”

Another reason data center investors are paying closer attention to Texas is its cost benefit.

“In 2013,” explains Berzina, “Texas became an extremely compelling option for all companies looking to locate large data centers. We did this by legislating the rebate of the state sales tax for hardware, software and electricity. So on a $100-million expense for hardware and software, $6.25 million stays in the hand of the company. Intertwine this incentive with an independent state electricity grid and the option of using the largest array of wind energy sources in the nation and you can see why world leaders like Facebook have chosen Texas and Fort Worth this past June.”

A plentiful and reliable power supply is top-of-list important to any data center. Add Facebook’s insistence that its energy be reliable and renewable and redundant, and the site options quickly shrink.

“The fact that Texas is on its own grid is interesting in that it gives us some redundancy,” Peterson relates. “We have other data centers on different grids, so if one were to go down, we are on others that are not as connected or dependent on that one grid. So there is some redundancy in place for running these critical facilities.”

Texas being a deregulated energy market is no less significant.

The ‘Major Deciding Factor’

“In a lot of other markets that are regulated, you really don’t have a choice in the source of the energy,” Peterson points out. “You’re dependent on the utility and what they have as their generation mix – part coal, for example. It ranges the gamut, depending on the state and how things work. In Texas, given that the market is open, we can choose the source and figure out who we want to supply energy to us. We found a project in the development stage that will provide 200 MW of new wind energy to the grid, and that covered our energy needs for the development of our site. Having that choice and being able to determine the project source and how we wanted to bring those resources to our facility and to make sure we really were using renewable energy — it was really up to us to determine. We continue to work with utilities in other, regulated markets — we’re working with a regulated utility in Iowa, where we were able to develop a 100 percent wind energy solution as well. It’s just a lot easier and faster when we can find the locations that give us more of that choice. That for us was one of the deciding factors — one of the major deciding factors in our coming to Texas.”

Facebook’s Luleå, Sweden, data center is powered 100 percent by hydro, notes Peterson.

“At the scale we’re looking at, wind is one of the more cost-effective ways to get to the 100 percent clean and renewable energy goal. But we consider other options. At some other locations we are considering right now, solar is of interest as the cost of delivering that energy has been coming down over time.”

The number of factors Facebook seeks to balance in siting these facilities is “pretty significant,” says Peterson, so her team “keeps an open mind in terms of energy sources and how we might go about creating the next solution for the next site, which we’re embarking on right now. My team is always looking for interesting locations, and the time it takes us to find these locations is fairly significant.

“For the Texas deal, we started the site selection process a little more than a year before groundbreaking, and we used every ounce of that time to do what we needed to do,” she adds. “The locations we continue to look at become increasingly difficult in terms of the things we want to have in place in order to site a facility there. Internationally, that timeline is even longer — 18 months from when we begin [the site search] to when we start construction. We’re always looking for interesting locations. Given our growth and the lead times associated with these site selection projects, we want to get to the point where we have multiple sites ready to go if growth takes off, or if we need additional facilities as we continue to expand. One of our goals is to make sure we have an ongoing pipeline of very interesting locations that we can develop next.”