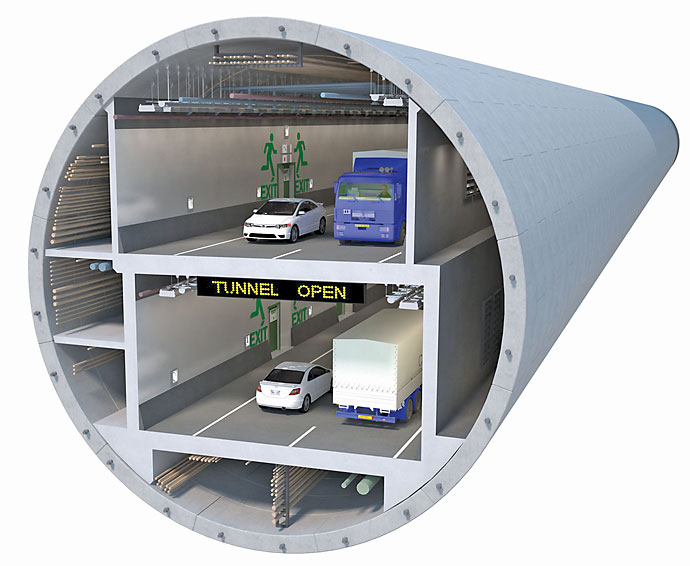

Workers at the Hitachi Zosen factory in Osaka, Japan, are currently working on the world’s largest tunnel boring machine. Next spring, the US$80-million giant drill will journey in pieces across the Pacific to Seattle, where it will be assembled into a 326-ft.-long (nearly 100-m.), 57-ft.-diameter (17.4-m.) machine that will bore underneath the city’s downtown. The 1.7-mile (2.7-km.) tunnel is the centerpiece of a $3.1-billion project to replace the city’s antiquated Alaskan Way Viaduct.

The viaduct is a double-decker bridge lining the Seattle waterfront that is vulnerable to earthquakes due to the Seattle Fault which runs through the area. It was damaged during the Nisqually earthquake in 2001 which rocked the Puget Sound region, causing an estimated $4 billion in damages.

On the east side of Seattle, the $4.65-billion State Road 520 and HOV Program project is under way. This includes replacement of the floating pontoon bridge over Lake Washington, another piece of infrastructure open to damage by earthquakes.

Paula Hammond, secretary of the Washington State Dept. of Transportation, says the state’s legislature prepared for its pressing infrastructure needs by approving gasoline tax increases totaling 14.5 cents in 2003 and 2005 to fund 421 priority projects totaling $16.2 billion. The tunnel and the pontoon bridge projects are by far the largest.

“With the gas tax we were able to put the money immediately to use and help us build things,” Hammond says. “It’s a two-fer with projects that not only help the Puget Sound area, but across the state.”

The 1950s-era viaduct was showing signs of age and deterioration before the 2001 earthquake further weakened the structure, but the earthquake heightened the need for its replacement.

“We have known we are vulnerable and have been working since 1997, thinking how to replace the viaduct,” Hammond says.

Hammond says the first concept for the project was a “cut and cover” tunnel, but that would have disrupted downtown businesses for an extended period. She said the technology of deep-bore tunnels came to the forefront during this period and the state took a leap of faith.

“When we get underground next year, there will be little notice by businesses.”

The southern mile of the viaduct replacement project, near the city’s port and sports stadiums, is being replaced by a new, wider roadway that meets modern earthquake standards. That segment is under construction and due for completion in 2013.

“As we open the tunnel in late 2015, and when we tear down the viaduct along the waterfront, there will be an opportunity for the waterfront to finally be developed,” Hammond says. “There’s an opportunity to develop something similar to San Francisco’s Embarcadero. There will be retail and tourism opportunities and it will be a great boon for the city.”

In a project viewed as complementary to the tunnel, the City of Seattle plans a major undertaking to replace its aging seawall, also prone to earthquake damage. The city placed a $290-million bond referendum on the Nov. 6 ballot to pay for this project, which replaces the three types of deteriorated seawall structures along the waterfront, constructed between 1916 and 1934.

The State Road 520 floating bridge over Lake Washington, officially Governor Albert D. Rosellini Bridge — Evergreen Point, is the longest such bridge in the world at 1.44 miles (2.3 km.). Like the viaduct, it is also long in the tooth and is a major transportation artery, connecting Seattle with the high-tech corridor on the east side of the lake, which includes Microsoft’s main campus.

“It’s been congested for a long time,” Hammond says. “The pontoons are aging and need to be replaced.”

The logistics of building the pontoons and getting them to Lake Washington is a major feat in itself. The floating bridge will require 77 pontoons, including 33 being built in Aberdeen and 44 in Tacoma. The Aberdeen pontoons are approximately 28 ft. (8.5 m.) tall, 75 ft. (nearly 23 m.) wide and 360 ft. (110 m.) long and are being towed 260 nautical miles (482 km.) to Lake Washington. The Tacoma-built pontoons are smaller.

At the project’s peak, it will employ 400 workers in economically challenged Aberdeen, a city of about 17,000 nearly 110 miles (177 km.) southwest of Seattle.

“Aberdeen is a part of the state that was impacted back in the 1980s when the timber industry went into the tank,” Hammond says. “It’s a very beleaguered area. It was great when we found they had the space and ability to house a pontoon casting basin.”

A floating bridge, rather than a suspension bridge, is used to cross Lake Washington because a suspension bridge would be far more costly due to the lake’s depth, according to the Washington DOT. The lake is 214 ft. (65 m.) deep at its deepest point. Conventional fixed bridges are more expensive to build in deeper waters with soft beds such as Lake Washington.

Engineers have designed the floating bridge so that additional supplemental pontoons could be added in the future to support the weight of light rail.

“It’s exciting for us right now,” Hammond says. “After years and years of analysis and community outreach and decision making, we are coming to the point to where this is where you build. People are pretty upbeat about it these days because the community is able to envision what it will be like when it is done.”

Malaysian Connectivity

One of the world’s great bridge projects is more than 80 percent complete in Malaysia. The Second Penang Bridge will connect Batu Maung on Penang Island with Batu Kawan on the mainland. The bridge, scheduled for completion in November 2013, is just under 15 miles (24 km.) long and will be the longest in Southeast Asia. The length over water is 10.5 miles (16.9 km.).

The Malaysian government says the $1.4-billion bridge will improve trade efficiency and enhance logistics systems by providing better connectivity and accessibility to the Penang International Airport, boosting economic growth in Penang.

The bridge will also be the longest bridge in the world that incorporates the High Damping Rubber Bearing system, which helps protect against seismic damage.

Jambatan Kedua Sdn. Bhd. is the concessionaire for Second Penang Bridge and is wholly owned by the Ministry of Finance Inc. The company is responsible for the construction, management, operation and maintenance of the project. In July, Jambatan Kedua congratulated UEM Builders for reaching the 75-percent mark with segmental box girder casting 50 days ahead of schedule. The method is being used to construct the approach span for the bridge. According to UEM Builders, their next target is to complete the casting by Dec. 20, 2012.

The first Penang Bridge opened in 1985 and connects George Town on Penang Island with Seberang Prai on the mainland.

Funding Shift

Terry Bennett, senior industry manager at Autodesk, a design and engineering software developer, says there has been a decided shift in how many infrastructure projects are funded. Autodesk serves the global infrastructure market, and its products are being used with some of the world’s largest projects, including the Panama Canal expansion.

As the world’s population grows and existing infrastructure decays, funding these enormous projects will be an increasing challenge. Bennett cites a recent report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development that countries need to invest $53 trillion in infrastructure projects over the next 20 years.

“We are starting to see more of a shift [in] where project funding is coming from,” Bennett says. “Traditional government funding is tight and we now have an onslaught of investment by private investors such as pension funds. They see a very good return on investment. There are always going to be some federal dollars and in some cases state dollars applied to infrastructure.”

Bennett says about 35 states have DOTs with dedicated public-private partnerships for infrastructure construction. He cites Virginia, Texas, California and Illinois as having good programs.