As Green Bay Packers fans make the thawing journey to Arlington, Texas, this weekend for the Super Bowl, some might be carrying a chip on their shoulder that has nothing to do with the Pittsburgh Steelers. It’s about a far weightier matter than tossing around a football. And that’s rolling a bowling ball.

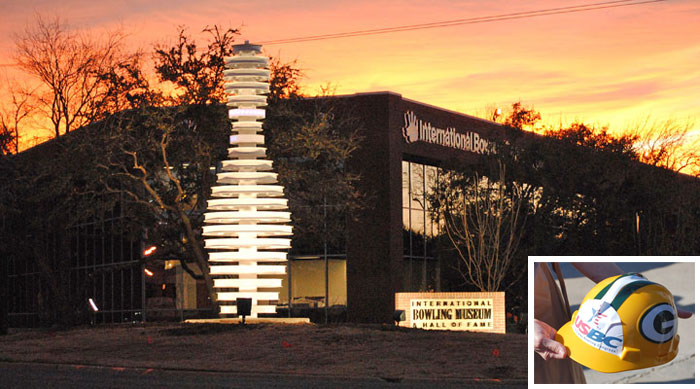

For Wisconsinites, the wounds are still raw from the March 2008 decision by the U.S. Bowling Congress to move its headquarters from Greendale, Wis., part of the the bowling capital of Milwaukee, to Arlington. The move was topped off by the January 2010 grand opening of the International Bowling Campus (IBC). The new complex physically reflects the integration of the USBC and the Bowling Proprietors Association of America (BPAA).

“Bringing together all of the leading entities in bowling under a single roof is a tremendous step forward in uniting and strengthening our industry,” said Steve Johnson, executive director of the BPAA, at the grand opening.

At the same time, even the winners were sensitive to the long-term attachment the USBC had had to Milwaukee.

“We were obviously very excited to have them come, but we were sensitive to the fact that it was in the Milwaukee area for 100-plus years,” says Robert Sturns, economic development manager for the City of Fort Worth since January 2010, who before that served in a similar post for the City of Arlington, and was closely involved in the attraction of the USBC project. “When people think of bowling, they tend to think of Milwaukee.”

The 103,000-sq.-ft. (9,569-sq.-m.) development in Arlington includes a testing and training facility, as well as the International Bowling Museum and Hall of Fame, which used to be in another bowling capital, St. Louis, but had to move to make room for development surrounding the new baseball home of the St. Louis Cardinals.

There were three inductees into that Hall of Fame last year: Pittsburgh Steelers Lynn Swann and Jerome Bettis, and longtime knuckleball pitcher Tom Candiotti, originally drafted by none other than the Milwaukee Brewers.

Texas Power Nexus

The $14-million IBC project is estimated to bring with it an annual payroll of approximately $9.6 million. Located at

, a former Halliburton facility, the IBC is in close proximity to the new Dallas Cowboys Stadium, the Rangers Ballpark and the Six Flags Over Texas theme park. In fact, it’s within shouting distance of the Judge Roy Scream wooden rollercoaster, constructed in 1980 — the year the Steelers became the first team to win four Super Bowls, and a full nine years before Jerry Jones bought a majority interest in the Dallas Cowboys.

Three years ago, the tussle for the IBC project was between the Milwaukee 7, a group heading up economic development retention and attraction efforts for the metro area, and the City of Arlington Office of Economic Development. Arlington offered an incentive package that included tax abatements, development fee waivers valued at $25,000, and the use of Chapter 380 grants. Those grants provide additional financial resources equal to 50 percent of incremental hotel occupancy tax revenues attributable to conferences and tournaments hosted by USBC for 10 years (an estimated value of $213,000), as well as a 55-percent tax abatement on value added to real property for those same 10 years. Perhaps most meaningful was a Texas Enterprise Fund award for $610,000, connected to the eventual creation of 198 jobs.

Bruce Payne, economic development manager for the City of Arlington, oversaw the city’s development services division at the time of the project’s attraction. He says there were some intensity-of-use issues to work through with regard to parking, “but we did work through it.”

The BPAA has been located in Arlington since the Cowboys’ first heyday in the 1970s, says LeeAnn Norton, director of meetings & events for the combined BPAA-USBC, with which she’s been affiliated for 14 years.

“It was always the vision of both that we needed to be together to run more efficiently,” she says. At one time, there was talk of moving everybody to a new complex in Florida, but “that basically never came to fruition,” she says. Finally, economic and industry circumstances three years ago helped force the issue: “If we were going to continue to grow our industry and run as efficiently as possible, we needed to get together,” says Norton. Executives from both organizations, including former BPAA Executive Director John Berglund and USBC President Jeff Boje, led the process, which early on focused on just the two cities. The empty building a block away from BPAA beckoned, as did the cumulative incentives.

The Milwaukee-area team tried to match the offer, including two alternative locations in Cudahy and Milwaukee proper, and financial support from the state and municipal authorities. Support from the press was there too: “You might as well make Oshkosh the rodeo capital of America and transport the Alamo to Sheboygan,” wrote sportswriter Frank Deford in Sports Illustrated in February 2008. “Bowlers of the world, unite. Have another brewski and keep bowling where God meant it to be.”

In Milwaukee 7 meeting minutes from March 13, 2008, the headquarters was characterized as a $50-million business, and leaders cited the strong influence of the BPAA on the process. The week before, the Milwaukee and Arlington teams had traveled to Atlanta to make their final pitches — much like cities do in trying to land a Super Bowl.

“I remember walking out the door as they were walking in,” recalls Sturns.

Asked to recall his experience of the relocation, Greendale Village Manager Todd Michaels says it can be summed up in once sentence: “We didn’t have much of a chance, if any.”

Sturns says the USBC leaders, after 100-plus years in Milwaukee, were the hardest to convince. And the Milwaukee economic developers brought an all-out blitz to keep them up north.

“It was something no one there was taking lightly, and they tried very strongly to keep them there,” says Sturns. “It was kind of a painful thing for them, as if somebody grabbed the Cowboys or Rangers from Arlington. So we were sensitive to that aspect, and wanted to ensure that the transition was as smooth as it could be.”

Norton affirms that the voting was close. But ultimately the advantages of combining won out over sentiment.

“Both organizations had human resources, finance and meetings and events departments, and we’d spend time flying back and forth or teleconferencing,” says Norton. Now those teams can integrate, and sit down in the same room. “There were hurt feelings in the beginning, but people have seen the efficiency, and we get a lot more accomplished than in the past.”

Norton’s meetings and events department was one of the first to integrate, she says, and “the cost savings have just been astronomical.” Those flights to meetings are fewer now, but if they’re needed, “we’re close to Dallas-Fort Worth and can get anywhere in a direct shot,” she says. “And we don’t have the weather issues like Milwaukee does.”

With a quality vacant building awaiting, and the coincident move of the hall of fame, she says, “the timing was perfect to do everything.”

No Joke, Big Bucks

“It was a natural fit with other tourism we had,” says Sturns, whose eyes were opened to just how lucrative the bowling crowd can be. “While bowling is not a sport that would immediately fall off your lips with baseball, football and basketball, they wowed us with some of the national tournaments they had been putting on.”

The economic development potential of big-draw associations and events, especially in sports, certainly is not lost on the communities that in recent years have vied for such prizes as the College Football Hall of Fame (now going from South Bend, Ind., to Atlanta), the NASCAR Hall of Fame (Charlotte) or the Boy Scout Jamboree. The huge Cerner Corp. investment in Kansas City, Kan., announced a year ago, includes substantial investments involving professional and recreational soccer facilities adjacent to Cerner’s campus.

In bowling’s case, it’s a matter of serving a USBC membership that encompassed 2.1 million members in the 2009-2010 season, bowling in 75,000 USBC-certified leagues. Sure, some 106 million people watched the Super Bowl last year. But in 2009, 71 million ball-rolling Americans did more than watch: They actually played the game, making bowling the No. 1 participation sport in the United States. Some of those bowlers probably even watched the Super Bowl and drank a beer between frames.

The annual USBC open tournament is a draw in itself, and it’s not just a few days or a week. Unfolding over a period of five months this year in Reno (where it’s gone many times due to that city’s facilities and good drawing power), this year’s tournament will draw more than 14,000 five-person teams (and, of course, their entourages). According to published reports, Reno and Wichita, Kan., were two early candidate cities for the IBC project, before it became clear the battle was going to come down to Milwaukee and Arlington.

For the record: Pittsburgh last hosted the tournament in 1909. Milwaukee hosted it in 1905, 1923 and 1952. The last time the Dallas-Ft. Worth area hosted it was in 1957. But work is under way to get it back.

“We could do it in the Cowboys’ stadium,” says Norton. “The footprint needed is about a 100,000-square-foot [9,290-sq.-m.] box, but we would have to take over the structure for six months. If there was a facility in Arlington we could use, we would do that. We’ve talked to the city on a number of occasions about it, but there is not a facility we could utilize for that period of time.”

Sweet Revenge?

The newly united bowling associations will bring their conventions to the Dallas-Fort Worth area for the first time ever in June 2011, staging them in Grapevine because Arlington simply isn’t big enough, says Norton. In fact, Cowboys Stadium can’t even handle the trade show. “We have 200,000 square feet of exhibitor space,” she says, “and the stadium main floor is about 110,000 square feet.”

However, the groups will lay down four bowling lanes on that stadium floor for the U.S. Women’s Open finals that week, “two lanes on each side of the star,” says Norton of the Cowboys emblem at midfield.

At the end of that tournament, a women’s champion will be crowned in Cowboys Stadium. The Cowboys themselves will be preparing for training camp, as they aim to end their 15-year absence from the Super Bowl. The Packers, meanwhile, might be sporting a new crown of their own.

To Milwaukee-area economic developers, such a scenario brings little satisfaction. After all, winning on the field of play is one thing. Winning or losing real jobs is another. But there is another side to the story.

Back in Wisconsin, a public review process has begun in the Village of Greendale for a proposed tax increment financing (TIF) district, where Simon Property Group is hoping to redevelop Southridge Mall, the state’s largest shopping mall, and parts of an adjacent commercial area.

The 10-acre (4-hectare) vacant property owned and once occupied by the USBC, is located nearby, but is not part of that district. In fact, the USBC, like a lot of folks these days, stands to take a hit on its property when it does sell it. It’s listed for approximately $5 million, though its most recent assessment was at $7.5 million.

However, it’s on the verge of being redeveloped itself… by Wal-Mart, in a reversal of the more familiar scenario involving communities scrambling to repurpose former Wal-Mart facilities.

“We expect to receive a proposal from them in the near future,” says Greendale Village Manager Todd Michaels.

The prospective reuse by Wal-Mart, though it doesn’t replace those 200 USBC jobs, holds its own when it comes to tax revenue.

“From the standpoint of real estate taxes, it could double,” says Michaels. “[USBC’s] value was somewhere around $7 million. We could be looking as high as $14 million or $16 million.”

Does that salve the wound a bit from the USBC relocation?

“That’s fair to say,” says Michaels.